|

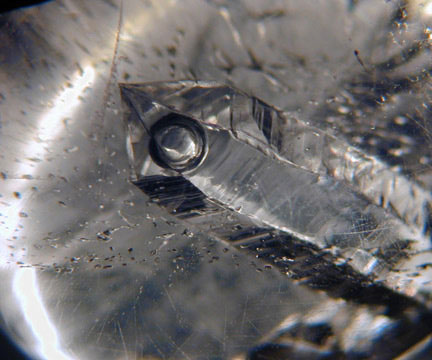

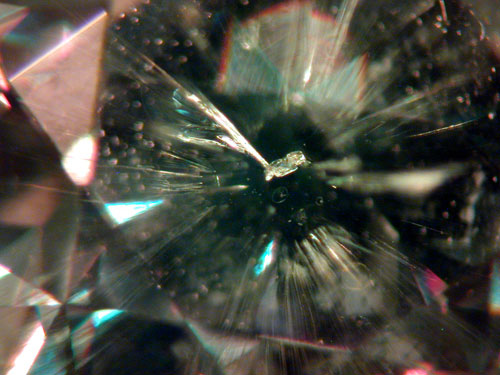

| This sapphire is screwed. A bizarre negative crystal seems to have grown in a corkscrew-like pattern (Photo: Pala International) |

In our quest to understand the complete story of gemstones we look internally to fully appreciate their external beauty. We’ve set up a new gallery to exhibit the educational and fascinating inclusions that aid us in our work. All the gemstones photographed have passed through Pala's hands in the past year. The photos were taken in an effort to learn and appreciate the gems that we see every day.

We can use the internal characteristics of gemstones to extrapolate the conditions in which they were formed, including temperature and pressure, and how that relates to the geological and geographical region they may have been associated with. The original locality of a particular gemstone can be traced back to the source by diagnostic features like a specific solid crystal inclusion or the presence of a 3-phase inclusion, just to name a couple.

The internal world of gemstones reveals mineralogical clues to trace a gem’s origin and what has happened to it on its way from the mine to the jeweler. Enhancements and treatments are even more of a factor today since the average gem collector has the infinite resources of the Internet to research and explore the secrets of the gem trade. Understanding internal characteristics can help identify the presence of heat treatment and distinguish a natural from a synthetic.

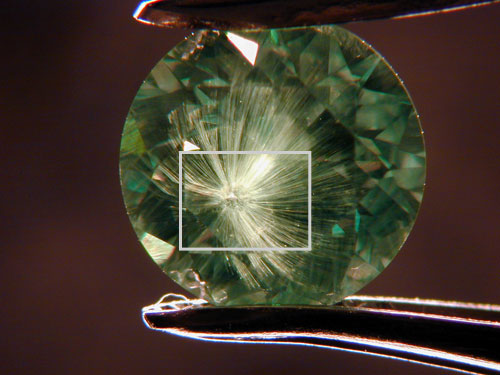

|

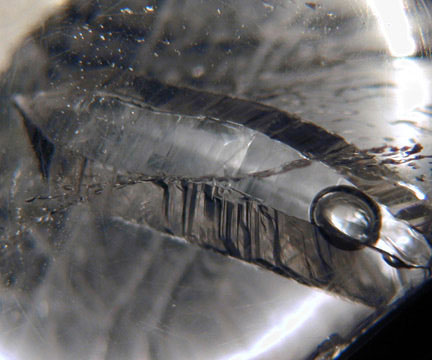

| One-eyed Willie. This bubble is in liquid inside of a negative crystal which is in a quartz cabochon host. In other words, a two-phase inclusion that happens to be in a negative crystal. (Photos: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

The father of modern day inclusion studies is the late Dr. Eduard J. Gübelin. His extensive research and cataloging of gems and their inclusions has established a standard by which gems are evaluated. Dr. Gübelin’s first major publication on inclusions is Internal World of Gemstones. His more recent work has been materialized through the Photoatlas of Inclusions in Gemstones, Volumes I & II. (Volume III will be available in the near future.) The Photoatlas series was coauthored by the world renowned inclusion specialist John I. Koivula. You can find a copy of these books and more about the coauthor J. I. Koivula here. Gübelin’s studies began during the winter of 1936–1937 and continued throughout his life. His work on gemstone inclusions includes over 20,000 photomicrographs, which are now housed at the Richard T. Liddicoat Library at the Gemological Institute of America headquarters in Carlsbad, CA. Read more on Dr. Gübelin here.

|

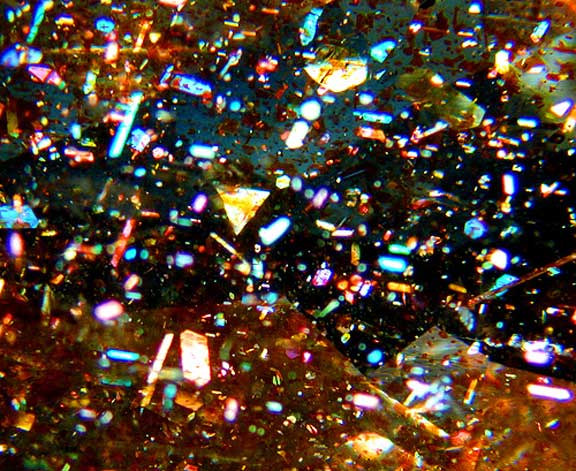

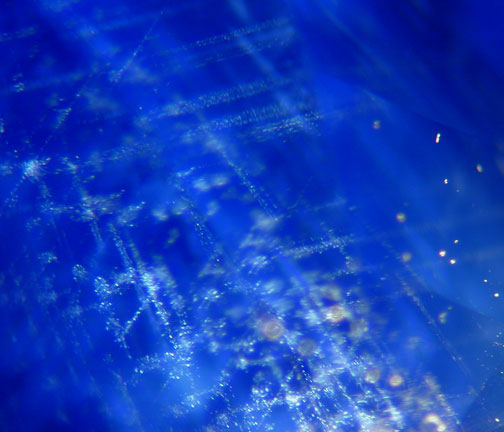

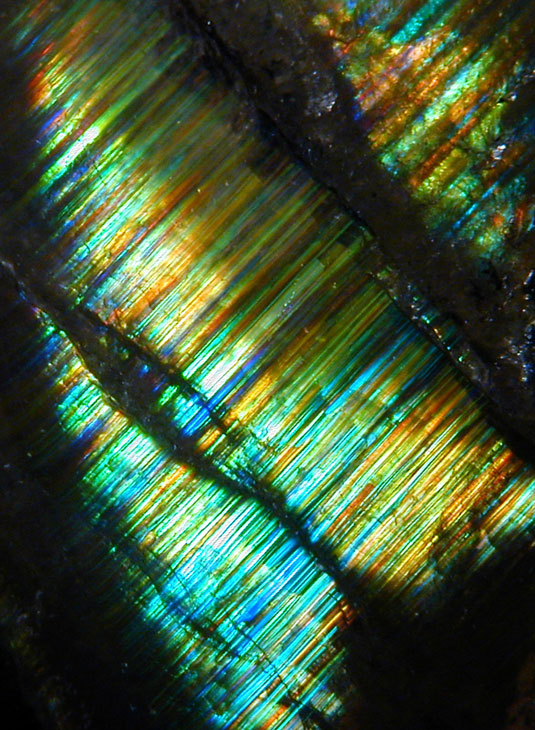

| A really good night inside a sunstone amongst the hematite platelets. This phenomenon is produced by interference colors from oblique illumination. See more from this gemstone below. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

We will revisit some of these classic internal features that originally inspired Dr. Gübelin to delve into the microscopic world. We also hope to bring the importance of this knowledge to the forefront of collecting and buying gemstones because of the overwhelming amount of treatments, synthetics, and imitations that are circulating in the gem trade. While highlighting some of the scientific aspects of gemology we also want to share the beauty and intrigue that can be found as we look just a little bit closer and expand our understanding of the genesis of gemstones.

|

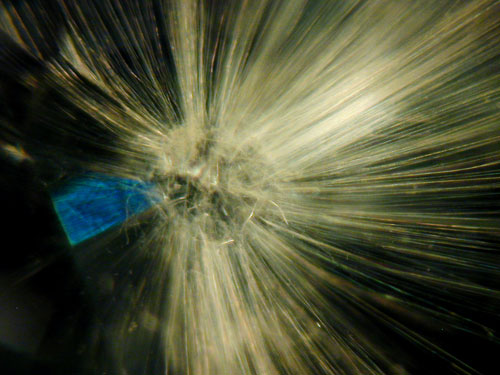

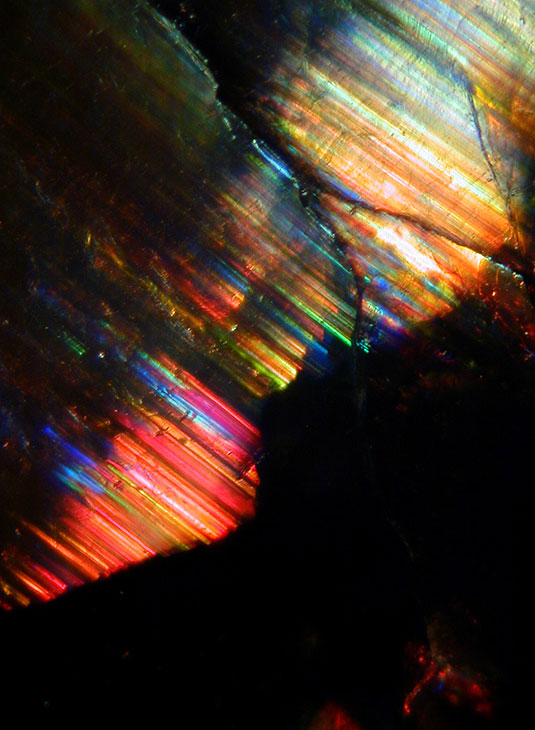

| Randomly oriented hematite platelets exhibit interference colors under oblique illumination. The host is a very unusual sunstone from Tanzania. (Photos: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

|

|

| Party colors. Photomicrograph showing the illuminated hematite platelets. Taken from Pala’s June 2009 featured gemstone. (Photo: Jason Stephenson) |

|

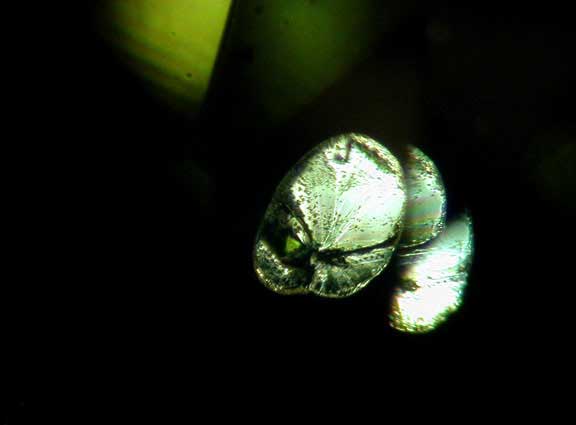

| Discoid cleavage in the classic “lily pad” shape. These formations usually have a tiny negative crystal near the center. This particular peridot is from Arizona. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

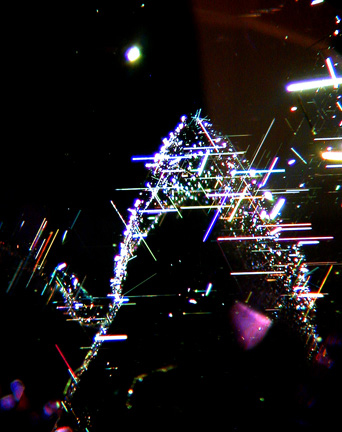

| Single black tourmaline needle in quartz. Precision cutting positioned the needle at the culet and extending perpendicular to the table so the tourmaline is reflected in a kaleidoscope-like effect. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

|

| Internal beauty. Needles and platelets flashing spectral colors following the octahedral-like phantom in a micrograph of a purple spinel from our August 2007 featured gemstone. See more inclusion photomicrographs here. |

|

| Another view of a negative crystal that seems to have grown in a corkscrew-like pattern in a sapphire. (Photo: Pala International) |

|

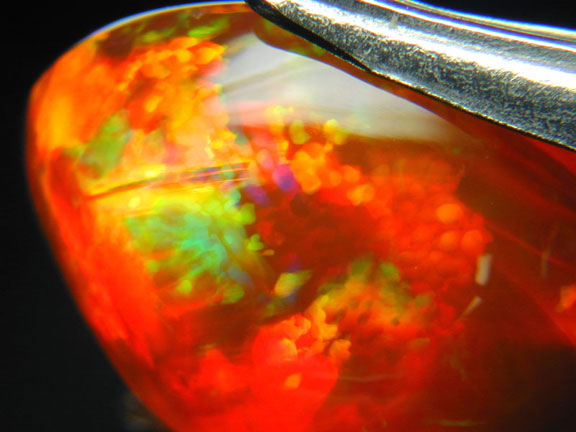

| Surreal sceptre. An unusual tube growth formation with larger terminating crystals in this Mexican fire opal, our July 2007 featured stone. See more photomicrographs here. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

| Firestone. This is an exceptional example of the red body color with play-of-color. From the Magdalena mining district. More information here. (Photo: Jason Stephenson) |

|

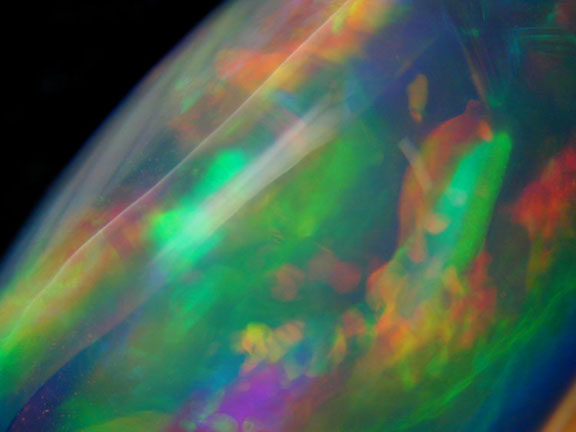

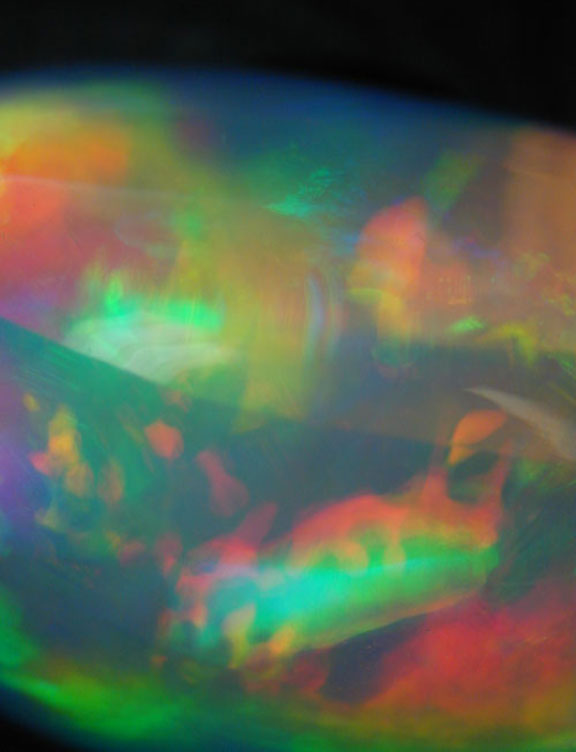

| Light rise over Planet Opal. A close-up view of the source of the color in this lloviznando opal. More information here. (Photos: Jason Stephenson) |

|

|

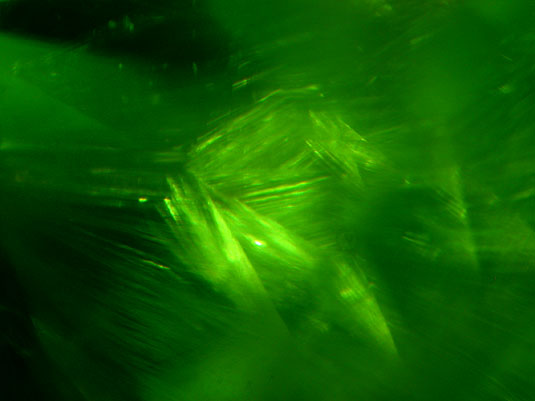

| Horsetail inclusion, the identifying mark of excellence in this Russian demantoid garnet, our May 2007 featured stone. See more on this gemstone here. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

| El Caballito Corriendo… If you let your imagination wander you’ll see him charging out of the verdant ground of this demantoid garnet. Read more about this photomicrograph. (Photo: J. Thomas Shofner, Palmetto Gems) |

The two inclusion photomicrographs included below were featured in the write-up on our featured gemstone for July 2009.

|

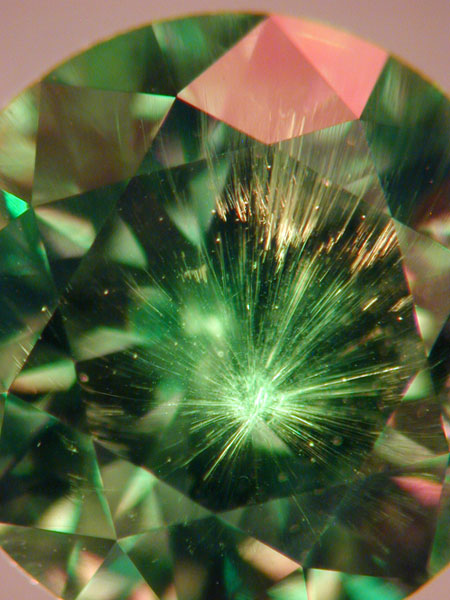

| Aurora adamantis. The aurora-like inclusions above are actually interwoven bands of horsetails. This is from a 2.33-carat round, 7.3 x 5.0 mm. (not from our featured gemstone). (Photomicrograph: Jason Stephenson) |

|

|

| Pow! An inclusion mimics a firework spray. From a 1.21-carat round, 6.0 x 4.0 mm. (Photomicrograph: Jason Stephenson) |

|

The following demantoid garnet photomicrographs are taken from Demantoid Disclosure: The ins and outs of reporting treatment and locality.

|

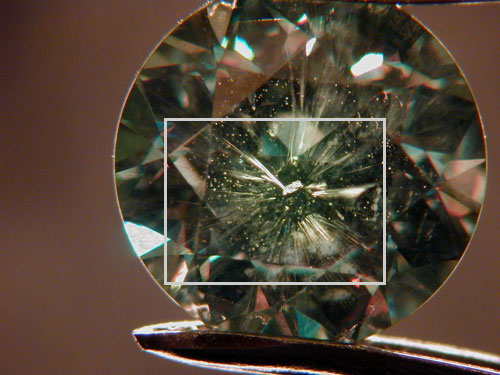

| Unidentified crystal at the center of the horsetail nebula. From a 2.81-carat round, 8.0 x 5.4 mm. (Photos: Jason Stephenson) |

|

|

| Classic radiating horsetail inclusion with distinct core. From a 2.25-carat round, 7.2 x 5.0 mm. (Photos: Jason Stephenson) |

|

|

| Unidentified halo inclusions of varying sizes along chrysotile needles. Halos similar to these are found in varying sizes within many demantoids. (Photo: Jason Stephenson) |

The following demantoid garnet photomicrograph is taken from The World of Demantoid, regarding the cover story of ICA’s Summer 2009 issue of InColor, written by Pala’s Jason Stephenson and Stone Flower’s Nikolai Kouznetsov.

|

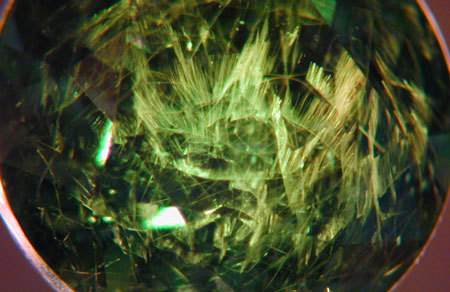

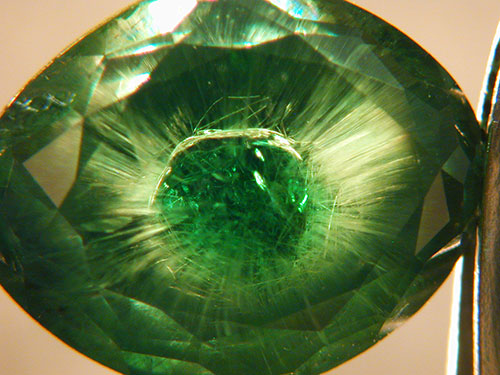

| The eye of demantoid. Jason thought this might be good “eye” candy for those gem lovers who like to delve into the microworld: “This 10.32-carat Russian demantoid happened through our office the other day, and we couldn’t help but try to capture the unusual scene within. In the heart of the jewel we find a pure nodule with radiating horsetail fibers, suggesting a two-stage growth of the demantoid crystal, but definitely some complex genesis at work…” (Photo: Jason Stephenson) |

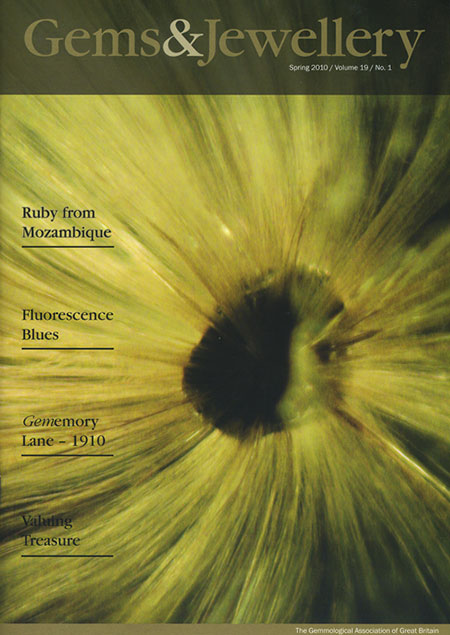

In Spring 2010, Gems & Jewellery, the periodical of The Gemmological Association of Great Britain (Gem-A), published its seasonal issue featuring a fantastic horsetail inclusion in a demantoid garnet from Russia (below). The photo was taken by Pala’s own Mia Dixon.

|

|

| Silk. Needly, cloudlike inclusions, known as silk, are visible under magnification, proof of the absence of heat treatment. See more here on this Kashmir sapphire, our January 2007 featured stone. (Photos: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

|

|

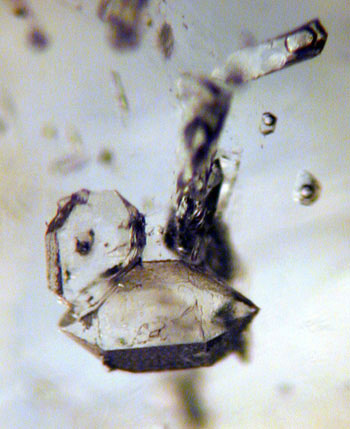

|

| Euhedral quartz crystals in a Japan-law twin-like formation, suggest syngenetic formation with the beryl host. Also notice the two-phase inclusions. From this Pala District pegmatite. (Photo: Jason Stephenson) |

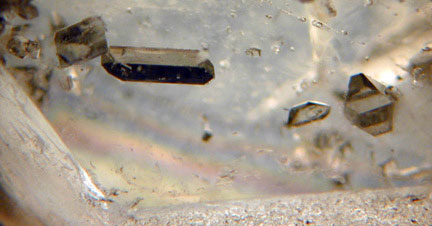

|

| Confetti of single-crystal inclusions, most likely quartz and feldspar, with some small two-phase inclusions. This material also produced some bubbles trapped within negative crystals. From this Pala District pegmatite. (Photo: Jason Stephenson) |

The two inclusion photomicrographs included below were featured in the sixth annual John Sinkankas Symposium, held in April 2008. The subject of the conference was garnet.

|

| Inclusions in garnet. Iridescent pattern seen in an andradite garnet from Hermosillo, Mexico. The pattern results from a superficial chemical disintegration of the outermost layers of the crystal. (Photos: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

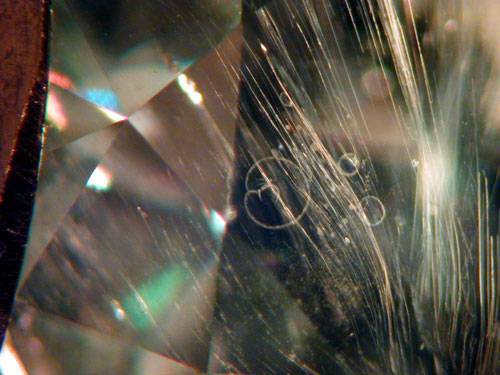

The following photomicrographs demonstrate telltale signs of lead-glass filling, which we discussed in our September 2008 Gem News.

|

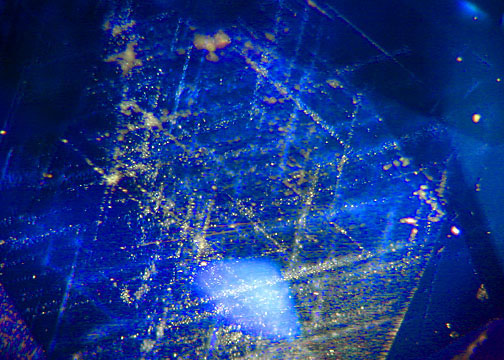

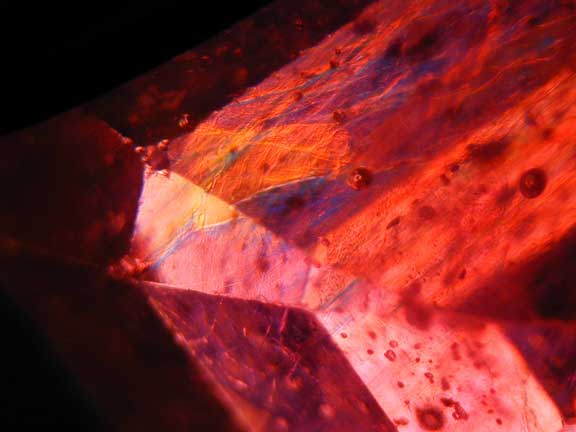

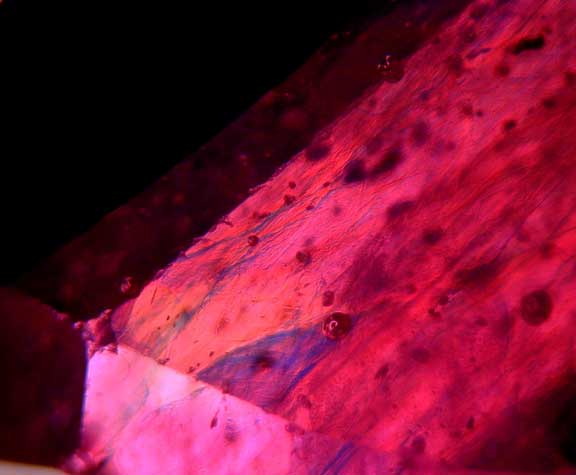

| Flashy: Blue and orange flash effect seen along structural fractures, a key identifying feature of glass-filled rubies. (Photos: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

|

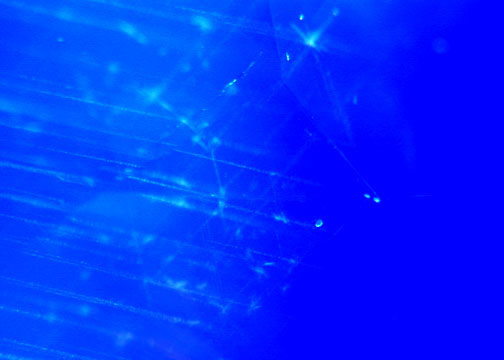

| All wet: Lead glass filled rubies immersed, showing bubbles and color concentrations along fractures. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

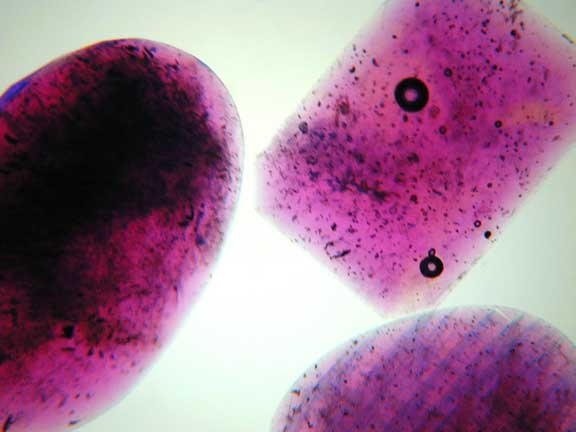

| Bubble trouble: Gas bubbles like that shown above, are indicative of lead-glass filling, and are easily seen with a microscope. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

The phenomenon illustrated in the following photomicrograph was discussed in our April 2009 Gem News.

|

| Needlework. A 3.22-carat Mozambique paraiba tourmaline (9.5 x 8 x 5.4 mm) showing brick-colored growth tubes. (Photo: Jason Stephenson) |

The varied inclusions diplayed in the following photomicrograph, from a spinel from Tajikistan, are identified in our March 2010 Gem News.

|

| Big rosy red in bloom. This photomicrograph is from Pala International’s featured gemstone for March 2010. (Photo: Jason Stephenson) |