June 2015 Newsletter

Sainte-Marie selfie. From left, Will Larson, Giancarlo Parodi (Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle), unknown (in back), Bill Larson and Carl Larson. Taken at the Sainte-Marie show last summer.

Table of Contents

Shows and Events

- Thirteenth Annual Sinkankas Symposium – Opal: Proceedings Available

- Mineral & Gem à Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines: June 25–28, 2015

- Mineral & Gem Asia: June 27–30, 2015

- The Crystalphilia of Björk and Marina Abramović

Pala International News

Minerals and Mineralogy News

Industry News

Special Feature

Shows and Events

Thirteenth Annual Sinkankas Symposium

Opal: Proceedings Available

Pala International is publisher of this year's Sinkankas Symposium proceedings on the topic of Opal. The volume is edited by GIA's Stuart Overlin, designed by Faizah Bhatti, with production coordinated by Juan Zanahuria, both also of GIA. Featured are 120 pages of original material accompanied by more than 150 photos.

The following authors contributed to this edition: Dr. Eloise Gaillou, Dr. Raquel Alonso-Perez, with Jason Tresback and Theresa Smith, and also Bill Larson, Renee Newman, Helen Serras-Herman, Robert Weldon, Nathan Renfro, Dr. James Shigley, and Si and Ann Frazier. Principal photography was provided by Robert Weldon (including the cover image), Mia Dixon, and Jurgen Schutz.

Copies of the Opal proceedings can be ordered from Roger Merk. The price is $35.00 plus shipping. (Shipping to Canada is $19, and $24.50 to most countries in Europe.)

45 Nationalities Celebrate Opal Capital Centennial

Opulent opal. This 11.40-carat white opal is typical of that produced in Coober Pedy. It's from the 8 Mile mine. Inv. #16028. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul)

It's 100 years since opal was discovered by 15-year-old gold prospector Willie Hutchinson in what is now Coober Pedy, South Australia. The outback town, founded the year after the boy's discovery, is namesake to a 5,000 square kilometer gemstone field that provides most of the world's precious opal; only 10% of the field has been mined, according to the town's website. Yet 250,000 mine shaft entrances dot the landscape, due in part to a ban on large-scale operations, per Wikipedia. While the town has a tiny population of only 3,500, the inhabitants come from an estimated 45 nations.

BBC has marked Coober Pedy's centennial with an examination of the prospect (ahem) of this Australian opal being designated Global Heritage Stone Resource (GHSR). No stone has yet been so designated, but an international group of geologists is to recognize stones that have played a significant role in human culture. Thus, other contenders, according to BBC are Portland stone, Carrara marble, Sydney sandstone and Norwegian larvikite. Should Australian opal be chosen, similar opal from other localities could not be called "Australian." Including opal in the GHSR pantheon has its detractors, who feel that the designation was meant for building-stone exclusively, not precious stone.

Mineral & Gem à Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines:

June 25–28, 2015

The 52nd Sainte-Marie show will be held June 25–28, with the first two days limited to trade only. This year, Bill and Will Larson will attend the show along with spouses Jeanne and Rika Larson. Friend and fellow gem dealer Mark Kaufman also will be in the party. They will be meeting up with Patrick and Pia Dreher. (See this Ganoksin.com blog entry by Robyn Hawk regarding Patrick Dreher's recent appearance at GIA.)

The 112-year-old swimming pool building is the site of a display of rare minerals and fossils by ten renown collectors and dealers. Lectures also take place there. We're delighted to see our old friend Eloïse Gaillou, who has relocated to Paris, and who will speak on her subjects of expertise.

A symposium in English will be held in the Mine d'Argent (200 meters from the Gem Zone) on Friday at 7:30 p.m. The themes:

- Eloïse Gaillou, associate curator of the Musée Mines ParisTech (School of Mines): On the Importance of Mineralogy Museums: Display and Collections

- Jolyon Ralph, Mindat.org: Mineral Collection Cataloguing in the 21st Century

- Victor Tuzlukov, lapidary: What Good Gem Cutting Is and Why It's Worse Than Exclusive

- The Amber of Kaliningrad: presented by the Musée de l'Ambre de Kaliningrad (in conjunction with the exhibition Baltic Stone of the Sun)

And these lectures, which we listed in our sibling publication, Palagems Reflective Index (only the first will be in English and French):

- Victor Tuzlukov, lapidary: Philosopher's Stone – When Wisdom Sparkles in the Precious Stone (in conjunction with his curation of Lapis Philosophorum)

- Yellow Amber: presented by the Musée de l'Ambre de Kaliningrad (in conjunction with the exhibition Baltic Stone of the Sun)

- Michel Boudard, gemologist: A Look at Gemology, specifically the intersection between stones of greater carat weight and the treatments that may lurk within; an aid to the prospective buyer

- Jean-Jacques Chevallier, lecturer: Geological History of the Earth ("The study of the infinitely small explains the infinitely large")

- Eloïse Gaillou, associate curator of the Musée Mines ParisTech (School of Mines):Treatment and the Synthesis of Diamond

- Jean-Christian Goujou, lecturer: The Minerals of Metamorphism

- Alain Carion, lecturer: Meteorites and Their Impacts

In addition to the above-referenced exhibitions, the following also will be presented.

- Exhibition of the INETPhoto Contest: an international competition for photographs and graphic art about Mineralogy and Micro-mineralogy

- Minerals and Paintings: an exhibition curated by Jörg Thomas and Andrée Roth

- Jewelry – Silver Arsenic: Remarkably, this exhibition will take place in situ—along the vein of the Gabe Gottes silver mine, 6 km away from the Sainte-Marie show's Mineral Zone

- The Staurolites of Russia: an exhibition of "cross-stones" curated by Jean-Claude Leydet

Finally, our good friend and mineral dealer Alain Martaud curates The Prestige Exhibition. Entitled simply, Alpes, the display will pay homage to the mineralogical bounty of the 1000-km arc of mountains that stretches from north of Corsica to Austria and Slovenia. Among the Alpine varieties coveted by collectors: epidot, garnet, fluorite, emerald, quartz and gold. Specimens to be displayed will be loaned from local and national museums, as well as collectors both prominent and obscure.

Alain Martaud, curator of this year's L'Exposition Prestige, also is the author of the trilingual volume, The Minerals of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. The book is available from the show's online store.

New in 2015: The Sainte-Marie show continues to cater to the colored gemstone lover this year with Le Pôle Aalberg, an addition to the show's Gem Zone, featuring the full range of creation, luxury and fashion.

- Le Swanky Area: bijouterie et joaillerie and designers both traditional and contemporary

- Le Trendy Corner: fantasy designs and fashion accessories

- Le Gem Fashion Show: a scripted jewelry presentation offering "unusual perspectives in response to hidden desires." Ooh la la!

Mineral & Gem Asia: June 27–30, 2015

In our last newsletter, we included a brief mention of the upcoming Mineral & Gem Asia show, being held later this month. Below, see the show's brochure.

To see the brochure interior, click here.

The Crystalphilia of Björk and Marina Abramović

In this edition of our newsletter we look once again at artists who are incorporating mineral specimens into their work. —David Hughes, editor

Björk's Crystal Method

In his Museum of Modern Art profile of Icelandic singer Björk's music, and music in general, U.S. music critic Alex Ross employs much metaphor: Shakespeare's "music as the food of love," a refutation of Schopenhauer's "music as a universal language," John Cage's musical genres as many streams leading to an ocean leading skyward, music as spreading populations, genre as gerrymandering by musical politicians, breath as music (Björk's grandfather snoring: musique concrète), spine-like flexibility in the voice.

Early on in the article, regarding Björk's musical taste—ranging from Gustav Mahler's 10th Symphony to Public Enemy's It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back—Ross likens her sonic predilections to isolated land masses of preference coming together rather than drifting apart, "re-forming as a supercontinent." In late April, science writer Peter Spinx told his readers that the recent earthquake in Nepal was a manifestation of the actual tendency towardAmasia—a gathering of all continents, taking place in tens, perhaps hundreds of millions of years' time.

On the cover of Biophilia, Björk plucks her bodice with one hand while holding what looks to be Mexican creedite with the other.

Björk herself employed terrestrial imagery in a song from her 2011 album Biophilia, which emerged from her concern in 2008 for Iceland's natural resources during the country's financial meltdown—and the literal meltdown of local aluminum smelters. "Crystalline" was inspired, according to a page devoted to the song, by urban transit intersections amidst office towers, contrasted with complex, compact city grids, and Björk's desire to mirror each nexus sonically. "To me crystal structures seem to grow in a similar way," she said. The song spawned a host of remixes, many with their own associated images of mineral specimens: pyrite, calcite on amethyst, some hefty quartz crystals, fluorite. Below are just a few examples.

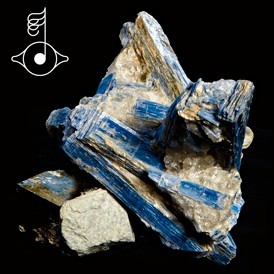

Kyanite crystals, possibly from Switzerland, are the "cover" image for the digital download of Björk's "Cosmogeny" remixes by Matthew Herbert. The title refers to the origin or evolution of the universe. Björk also holds the specimen in an image for the Serban Ghenea mix of the same song.

In the video for "Crystalline," crystal forms bloom and fade, within and without biospheres. They push up like icy shoots, break up like snow cone pellets.

"She's a Rainbow." The cover art for the Biophilia remix album, Bastards (get it?), reminds us of the multicolored strata of Zhangye Geology Park in north-central China. The above image essentially is an outtake from the video for Björk's "Mutual Core (Matthew Herbert's Teutonic Plates Mix)," also from Biophilia, which makes a sensuous mess of earthy delights.

Björk Retrospective at MoMA Ends Sunday

Museum-goers in New York still have a week to see "Björk," the retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. You've seen some of it on album covers, photo spreads and videos, but now you have a chance to share space with the instruments, costumes and objects (including minerals?). For Biophilia, Björk created some of the instruments—gameleste (gamelan celesta), pipe organ, gravity harp, and Tesla coil—and these are installed in the museum lobby to play songs from the album. A sound and video installation has been created for "Black Lake" (see teaser below), along with nearly twenty years' worth of videos. And what would a Björk survey be without technology? An interactive experience also is offered, as well as a final discussion on her work this Thursday at 11:30 a.m.

In "Black Lake," Björk takes on the role of a rent earth mother. The song cycle from which this is taken is Vulnicura, i.e., cure for wounds; in this case the wound is her separation from longtime partner, artist Matthew Barney. The relationship and breakup recalls the symbiosis and troubles of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, whose "One Woman Show, 1960–1971" opened at MoMA last month.

Everybody Must Get Stoned: The Interactive Art of Marina Abramović

Just as John Lennon and Yoko Ono famously mixed their lives with their music and art, notably so with their Wedding Album,* performance artists Marina Abramović and Ulay conceived of their personal relationship as artistic expression itself. In fact, the years they were together, 1976–1988, and the resultant output are known as Relation Works. In 1980 they conceived of a piece that would seal their relationship: walking towards each other, and into marriage, from opposite ends of China's Great Wall (or about 5,000 km of it). Permission wasn't granted to perform The Great Wall Walk for eight years, in the course of which their relationship dissolved, but the performance was realized, minus marriage, as Abramović recalls in a MoMA interview.

Sharp-Cut: The Power of Stones is an interview with performance artist and photographer Tathy Yazigi, who is also a facilitator of the Abramović Method at SESC Pompeia in São Paulo, site of Abramović's recent retrospective.

The year after Great Wall Walk, Abramović began visiting Brazil, according to the artist's website,

studying crystals and precious stones, and their influence on the human body and mind. Geological formations inspired Abramovic to use this powerful material to create Transitory Objects, on view at her retrospective at Terra Comunal + MAI, as well as sculptural pieces that serve as furniture—such as chairs and beds—to be used in the Abramovic Method.

The retrospective (its title is Portuguese for "Communal Land"), ended May 15 in São Paulo at SESC Pompeia, the cultural hub of a Brazilian commerce group. (Read a Google translation about the retrospective here.) Transitory Objects were created between 1990 and 2000 and, like most of Abramović's work from then until now, the objects require the participation of the "viewer." Most of the objects are created from, or contain, crystals, which the artist considers to be "energy radiators." Eyes will roll, of course, but if Abramović is a sort of shaman of the arts, I am reminded of something practitioner Jez Hughes (no relation) said regarding the pragmatism of healing, including sleight of hand. "Only Western shamans are so precious about this," he told skeptic Mark Hay, who wrote last year's "Do Shamans Still Believe in the Magic of Shamanism?" The spiritual element is in play, Hughes says, but shamans understand that the human mind needs "tricking" in order to believe its way into healing.

For a book-length discussion of the shamanic roots of the performing arts, see Rogan Taylor, The Death and Resurrection Show: From Shaman to Superstar (London: Anthony Blond, 1985).

__________

* The box of Wedding Album contains: a facsimile of their marriage registration; the album itself, which in part commemorates their "Bed-In" honeymoon and call for peace; a compilation of the international press clippings generated by their marriage; a slice of wedding cake in a plastic sleeve, titled "Bagism"; a poster of images titled "The Wedding"; a trifold of photos and doodles regarding the marriage and honeymoon; a four-panel photo-booth reproduction; and a "Hair Peace / Bed Peace" photo postcard. Lennon created a series of drawings based on their wedding. I happen to own a copy of "I Do," estate-signed by Ono.

Pala International News

Pala's Featured Specimen: Copper in Calcite

Pala International has re-acquired a calcite with copper inclusions from the Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan. It was formerly in the collection of Ben Williams, which will be featured in an upcoming edition of Mineralogical Record. This specimen was our featured item for April 2011 and we're delighted to offer it again.

Calcite with copper inclusions from the Keweenaw Peninsula, Copper District, Michigan, 3.5 x 2.5 x 2 in. Price available upon request. (Photo: Jason Stephenson)

Here's the description we gave the first go-round:

It has a beautiful scalehedron structure, a massive white calcite in the core and a clear outer layer including the peak of the crystal, which is transparent. The center layer is a brilliant copper phantom that scintillates in the light.

With impressive size, shape and color this specimen is definitely an icon in the mineral world. No damage, no repairs, just a pristine beauty.

This specimen was collected by Ben Williams’s father, John Williams, in the 1860s. During this time period the elder Williams worked at the copper smelter in Hancock, Michigan. Ben would have been a young teenager at the time. These pieces were likely passed on from father to son and pre-date Ben’s arrival at Bisbee, Arizona by about 15 years.

Most of these copper-in-calcites came out in the 1800s and early 1900s. The two main mines that produced this rare blend were the Quincy Mine and the Franklin Mine around Hancock, Houghton Co., in Michigan.

See more on Keweenaw Copper District in the Mar–Apr 2011 edition of Rocks & Minerals (courtesy of 2010’s Rochester Mineralogical Symposium).

Another view of the specimen. It is now in the Ron Gladnick collection, about which Pala's Will Larson wrote in 2012, in the pages of Mineralogical Record. It has a beautiful coloration: internally bright, externally sporting a fine patina. (Photo: Jason Stephenson)

Interested? Contact us

The Inca King

Pala International's Will Larson goes the extra mile for a rare specimen

Pala International's Will Larson goes the extra mile for a rare specimen

In this story, Will Larson recounts his South American journey a year and half ago in pursuit of a beautiful and rare phosphophyllite, demonstrating to what lengths the discriminating dealer will go when presented with a fine specimen.

At the Munich Mineral Show in 2013 we met with one of my father's good Bolivian contacts. He told us of a very fine specimen that would probably be available on the market. It was said to be a very good phosphophyllite, still in Bolivia. Of course we were very excited, this being the "Holy Grail" of mineral specimens. The description sounded intriguing, but without photographs you never know the exact quality. Two weeks later, when we finally received images of the specimen and recognized its caliber we knew we had to jump on the chance to get it.

Sun king. The coveted specimen catches some rays. Phosphophyllite receives the second half of its name from phyllon, Greek for "leaf," in reference to its perfect cleavage. (Photo: Bill Larson)

On the Saturday that we received the emails, I was at a tech/video game convention with some of my friends from high school (an annual gathering for us in Anaheim). It also happened to be the weekend of the fall West Coast Gem & Mineral Show in Santa Ana. So my father took a break from the show and we met over sushi for lunch. As they say, the early bird gets the worm, and we knew this specimen would get a lot of attention quickly. On Sunday, after the conference, while at Disneyland with my then-fiancée Rika, I bought my plane ticket on my cellphone and by Tuesday I was on a plane to Bolivia. Below is the email to our contact that I'd sent before my first-ever trip to Bolivia. I was a bit nervous and quite excited.

Hello,

It's Will Larson!—Bill's son—I just called you. I will leave North America on Tuesday but land in Bolivia on Wednesday, November 13th [2013] at 6:25 a.m. at La Paz Airport. I will then leave Bolivia at 7:25 a.m. on Friday, Novemeber 15th.

Unfortunately a very short trip! I don't think [I'll have] so much time this trip to visit mines! Maybe next trip. Please get all phosphophyllite and vivianite ready for me to see. Also where should I stay?...thanks.

-Will

When I landed in Bolivia I met our contact and we had some tea and a Bolivian breakfast. It consisted of some over-easy eggs and beef so I didn't feel too out of place for my first Bolivian dining experience. The altitude in La Paz—nearly 12,000 feet—was something I didn't get used to in the short time I was there. Already just driving into the city from the airport I felt dizzy and sick to my stomach. It was about a hundred times worse than Denver (5,280 ft.).

Tea party. After a long flight, Will Larson enjoys an Bolivian breakfast in La Paz. (Photo: Paparazzo)

The fog of war. This guardrail graffito pays homage to the uprising of the people (la raza) that began October 12, 2003, leading to the resignation of President Gonzalo "Goni" Sánchez de Lozada. Two years later, one of the protesters, Evo Morales, would be elected President. (Photo: Will Larson)

On the first day I wanted to see the phosphophyllite I had seen in the photographs, and maybe any other phosphophyllites in the local market (if there were any). I pushed our contact to get the owner of the specimen to meet with us, but despite my efforts he wouldn't make it until the next morning. At least with a meeting set in 24 hours I felt I could relax a little bit. We went around town in the mid morning to find a hotel where I could stay. We found the first one to be completely booked up, but the second one, which appeared to be nicer anyway, had available rooms for my entire stay. (I've forgotten the hotel's name, but it was clean and other foreign tourists were staying there so I felt it would do.) Lunchtime consisted of a llama steak which was a bit like lamb and had a distinct flavor but was tasty nonetheless—another new experience under my belt.

Bilingual. Even vegetarians have choices with this eclectic menu. And the duck carpaccio is smoked in coca leaves, served with Amazonian almonds. (Photo: Will Larson)

I'll have the lamb, er, llama. As with the phosphophyllite, a menu description is only so useful. Above, wedges of llama and potato gateau, sautéed vegetables, green pepper sauce. (Photo: Will Larson)

At this point my contact started to make some phone calls to see if we could meet any other mineral dealers to see what they had for sale and what I was looking for. My contact had some specimens of his own to show me, but unfortunately, nothing that was worth buying. Two Bolivian mineral dealers joined us midway through lunch. They were from Oruro, a city about 4 hours by car from La Paz. One had brought some bournonites but they were heavily damaged and the other had some nice commercial magnetites but nothing special that I was looking for. The rest of the afternoon was pretty meaningless and I was exhausted so I took a nap. When I woke up, this being a town I'd never been in before I wasn't really up for adventure into the night. I just met up with my contact for a quick dinner and I was excited for the next morning's meeting.

Truckin'. Landscape workers are transported through the concrete jungle of La Paz, a metropolis of about 2.5 million people. The worker in the middle wears a traditional Andeanchullo hat that could have been knit from the wool of the llama Will ate at lunch. (Photo: Will Larson)

I woke up a little later than I had expected to, but journeys to far-off countries can suck the energy right out of you. I received a phone call from my contact and the meeting was on schedule: we would meet in the lobby of the hotel to discuss the deal. The meeting was set for 10:30 a.m. and I was there about ten minutes early. When my contact and his friend came in I was ready to see the piece. From the photographs I couldn't tell the quality of the specimen. Was it damaged or would there be cleaning needed? Would the piece be as good or better than I had hoped? Unwrapping it in my hand I was pretty excited to see the answers to all these questions. Now the question was how to deal with negotiations going forward, as there had been another American buyer trying to purchase the piece as well, but over the phone.

Holy Grail. Will Larson examines the phosphophyllite specimen in the lobby of his hotel. (Photo: Paparazzo)

It basically took all morning to negotiate. Bolivia being in the same time zone as New York made communication back in the States easy compared to when you're in Asia. I phoned my father and we discussed the piece, its strengths (many), weaknesses (none), etc. After that I put the final touches on negotiations, mainly arranging to wire the agreed-upon funds to the owner ASAP, and it was our specimen. I wrapped it up and put it in my most secure location. I was flying out the next day anyway, so there was no need to worry about being in possession of such a fine object in a foreign country for too long.

I did get hassled a little at the airport but not for mineral specimens; I happened to have left some bottle openers in my backpack from the Changsha Mineral Show and the security guys clearly wanted them. I happily handed them over and was on my way back to the U.S. The specimen made its way from Bolivia to California and now resides in the MIM museum. (See our "MIM's the Word from October 2013.)

The Inca King. Phosphophyllite from Potosí, Bolivia, 57 mm tall, 60 mm wide. (Photo: Robert Weldon)

Mineral and Mineralogy News

Whetting the Appetite for Color of a Subtle Sort

The current edition of Rocks & Minerals (90:3 [May/June 2015]) includes an article of interest to both mineral and gemstone enthusiasts. "Gem Apatite Localities" is contributed by photographer Mark Mauthner and curator Terri Ottaway. Both know their way around the subject; Mauthner is a former curator at the Gemological Institute of America (GIA); Ottaway is the current curator of the GIA Museum in Carlsbad, California.

Their survey of gem apatite localities is taken from existing gemological literature. It also relies on locality data from the GIA Museum's collection, which now includes the Edward J. Gübelin collection, which we pointed to in last month's sibling publication. Reading the article, you can compare data on some of the individual faceted apatites from the Gübelin collection, those included in the article as well as others, at the GIA Gem Project.

At first glance, one is struck by the range of hues in this material, often of a nuanced sort. For example, a 10.51-carat oval from Zimbabwe (you'll have to access the article to get the locality!) with shades of fir and sand. There are golden cat's-eyes from Sri Lanka and India, a blue one from Burma. Burma also has produced vivid, paraiba-like blue-green stones.

Mauthner has paired several of the cut stones with rough samples, like Kenyan yellow fluorapatites, and green and neon-blue fluorapatites from Madagascar. In a fun demonstration of polarized light at two settings, Mauthner plays tricks with two lovely, limpid Russian fluorapatites. In the first, the 2.24-carat emerald cut stone is lightly brushed with a wistful mint while its 1.6-cm-tall crystal partner is boldly blue; in the second image they have traded tints. (The phenomenon is due to the material's strong pleochroism, revealed by the polarizing filter.) Closer to home, there's a rosy crystal nearly as tall as the Russian—from San Diego County's Himalaya Mine—paired with a 6.33-carat cut stone from that same mine that would fit nicely, though somewhat subtly, into the collection of the Dowager Empress. The authors note that burgundy-red material from the Himalaya fades to pink with exposure to sunlight.

Fluorapatite on calcite with a dusting of pyrite. From Portugal, Inv. #21482. (Photo: Mia Dixon)

Yesterday and Yesteryear

One of the lectures at the upcoming Sainte-Marie show is on the topic, "Meteorites and Their Impacts," to be delivered by Alain Carion. These impacts can produce mineral material, like moldavite, named for a town in Bohemia, beautiful enough to be fashioned into jewelry, such as the brooch crafted by John Hatleberg, pictured below. The near-impacts can startle, such as the fireball—known as a bolide—that flashed briefly across the Czech border, in Slovakia April 6. It can also do damage.

Moldavite Brooch, designed by John Hatleberg, private owner. We featured this pin in a 2014 profile of Hatleberg. Moldavite is created from meteorite impact. This jewel is featured in the upcoming exhibition, "Out of This World! Jewelry in the Space Age," which we looked at last month in our sibling e-publication. (Photo: Tony Pettinato, courtesy Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh)

In his recent appearance on Charlie Rose, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson reminded viewers (at about 12:05) that just two years ago a bolide did cause damage, in Chelyabinsk, Russia, just across from the border of central Kazakhstan. "That happened to explode about twenty miles up," Tyson told Rose, "and that's high enough so that that energy gets deposited into the atmosphere and dilutes before it reaches Earth's surface. But even so, that was enough of a shock wave to shatter essentially every single window in the city—while people were looking out the window to wonder what the light was that they had just seen. Light travels faster than sound…." Were an asteroid of some size to hit our planet we'd be blown into the Stone Age, or worse.

Speaking of the Stone Age, last month an article titled "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya" was published in the journal Nature (521, 310–315 [May 21, 2015]), arguing that the oldest stone tools made by hand may have been used by a species that predates humans. A 3.3-million-year-old archaeological site in Kenya has yielded stone artifacts near hominid fossils that scientists have dated to 700,000 years before the Oldowan period (2 to 1.5 million years ago), which until now was the oldest archaeological period. This, notes the article's abstract, "marks a new beginning to the known archaeological record."

Industry News

A Conversation… Fine Minerals

PBS television affiliate KNPB broadcasts out of Reno, Nevada and covers a huge swath of the northern part of the state, from Tonopah in the south, Wells in the east, to Winnemucca in the north. Fortunately for our readers, the station also has an online presence, because on May 8, KNPB looked at the world of fine minerals in a segment from its A Conversation… series. Interviewed by host Brent Boynton were dealer Rob Lavinsky, videographer and collector Bryan Swoboda, and Garrett Barmore, museum administrator of the W. M. Keck Earth Science and Mineral Engineering Museum on the University of Nevada, Reno campus.

In the interview, Lavinsky talks about being mentored in collecting as a kid in Ohio, and Swoboda reminisces about his father Edward being a "godfather" in the mineral collecting world. The trio also discusses how the mineral collecting field has changed with the advent of the World Wide Web and social media. At one point in the twenty-seven-minute conversation, viewers are taken on a tour of the 107-year-old Keck Museum along with middle school students. The investment logic behind collecting is discussed as well as the effect on economies of specimen-producing localities.

Highlighted in the Conversation is the June 7 auction of Gerhard Wagner's impressive collection of tourmaline, an example of which, from Pederneira, Minas Gerais, Brazil, is cover star of The Mineralogical Record , above (the Jan–Feb 2015 edition, now out of print).

The KNPB presentation is an accessible and engaging introduction to mineral collecting and is recommended for anyone who is considering the hobby but might need a little nudge.

Special Feature

"Gold-smitten Mojave": George Holmes and the Strike of '33

Earlier this year we received a mineral specimen offer from Ryan Allen, who had inherited his great grandfather's "discovery rock." It is, Allen said, "the original half section of the ore that was not sent to the assayers and led to the founding of my great grandfather's mine, aka Silver Queen Mine in the Mojave Desert." Intrigued by the background material Allen sent, we asked for and received permission to write about his ancestor, George Isbell Holmes.

The Thirty-fourers

Last October, we touched on the stories behind the famous California gold rush that gave the forty-niners their name. Mary French Catlin, writing in the July 1976 edition of Lapidary Journal, tells readers that there was another rush eighty-five years later when George I. Holmes found gold on Soledad Mountain, about ten minutes south of the town of Mojave. The latter rush, Catlin writes, was sparked in part by a very detailed front-page article in the Los Angeles Times, December 4, 1934. "Huge Gold Strike at Desert Town of Mojave Reported." The article quoted experts as saying the strike was the most important since strikes in the early 1900s at Tonopah (ca. 1900) and Goldfield (1902), both in Nevada. In fact, according to theTimes, the Mojave strike attracted veterans from both those earlier strike, including a sitting and former U.S. Senator. (Oh, the good old days when politics lacked the taint of lucre…) And fifteen men from Cecil Rhodes's old South African group (from Mexico and India as well as South Africa), who already had taken a $3.5 million option on thirty-six acres of Holmes's claim.

By noon the same day of the exclusive December 4 Times story, newcomers from Los Angeles were out prospecting. "A little after the lunch hour" that day, the Times reported on December 5, "George and Ralph Wyman drove in, the rumble seat of their car filled with ore." "We hit a vein at the Middle Butte," George told the Times, referring to a rhyolite outcropping similar to that of the Silver Queen. The vein was "about fifteen feet wide," George said, "and we located it again 1000 feet farther." In six months, about $200,000 in gold ore had been sent to a smelter on San Francisco Bay. "Gold-smitten Mojave is hysterical tonight" over the new strikes, theTimes declared.

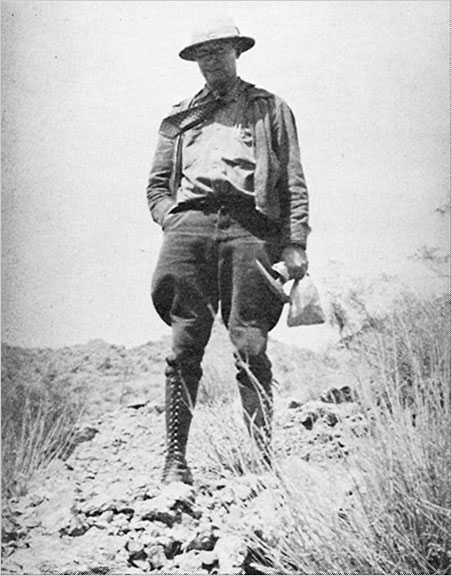

Holmes is shown prospecting on Soledad Mountain in 1935, the year after his historic gold strike.

Writer Catlin was lucky enough in the mid-1970s to interview Holmes's widow (and second wife), Sue Warner Holmes, over three days as they looked at scrapbooks and court documents. George Holmes had died a decade before of an occupational hazard: silicosis. But his enterprises hadn't been limited to mining gold. He mined lead, vanadium and wolframite. He was involved in Tom's Place, a recreation spot near Lake Crowley, northwest of Bishop, California. He had his hands in ventures as diverse as a shopping center and business complex in Arizona, a security service, and horse racing. But he was prospecting for gold again not long before he died.

Grandfather a Forty-niner

olmes's interest in mining began not long after his birth in 1903, in Lansing, Michigan. "There's mining in Michigan," Catlin writes, "copper, gypsum, coal, even some gold." (Our featured specimen above being a case in point.) Holmes's grandfather had been an unsuccessful forty-niner whose traveling companion died in the goldfields. After ten years in Texas, the family moved to Los Angeles. Catlin described their Maxwell roadster being loaded up like the Beverly Hillbillies. And that analogy can be extended a bit, with Holmes's first wife Hallie saying to the Times in December 1934, "There'll be a home in Beverly Hills, lots of little things I'd like," while her sister-in-law anticipated an ermine coat, a big car, tickets to the theater and opera and clothes to wear to them.

French-fried Find

eorge Holmes attended UCLA for a mining engineering degree as the goal, but, running out of money, he had to drop out in 1922. He worked a string of jobs at mines in California, Nevada and Arizona, eventually in Mojave in 1931, where he'd worked two years prior. He leased the Elephant-Eagle Mine there until he found the float, which led to the outcrop. It was Sunday afternoon, September 17, 1933, and Holmes was checking out unpatented public land that, rumor had it, might yield $12 to $14 a ton in ore. On the north face of Soledad Mountain was a 300-pound boulder. Whacking it revealed rhyolite porphyry and veins of silver and gold. He sawed off chunks. A part of the discovery rock—the one pictured below, now offered by Ryan Allen—was sitting on a coffee table in Sue Holmes's living room when Catlin interviewed her.

Silver Queen Mine discovery rock, 8 x 5 x 5 in., about 32 lb. In 1963, George Holmes told the Los Angeles Times, regarding the rock, "It's argentite. Very heavy. This piece weighed about 300 lb. before I sawed parts of it off." The rock is offered for sale by Holmes's great grandson, Ryan Allen. (Photo courtesy Ryan Allen)

Crushing some of what he'd carried home in a mortar, Holmes panned the dust in an frying pan. From his experience, the yield could be about $1,800 a ton. (Catlin quotes Holmes as saying his eye was so keen, he hadn't misread the value of a carload of ore by more than $5 a ton.) The first assay ran about $50 in silver, the same in gold. Holmes then located the vein from which the float had broken, trenching fifteen feet, hitting it at six feet beneath the overburden. Holmes was so poor he could only get work done on the mine by cutting in two friends at a quarter each; his father received another quarter. Holmes thought at the time he'd struck silver, hence the Silver Queen name.

Catlin details the other arrangements that were made between the partners. But when the vein of gold ran out after 10 feet, his partners got cold feet, selling out for $500 and $1,000. (The new partners were remunerated nicely for years.) Thirty sacks of ore carried down the mountain over six weeks paid for construction of a road at $2,000. Holmes was able to hire two workers after the first two car loads of ore were delivered. He was working 50 men when he sent 300 loads for an assay of $600,000 in 1934.

Gold Not Free

Holmes's early partners could have benefited from the words of a December 6, 1934 editorial, which acknowledged the difference between the Sutter's Mill strike—free gold—and the present one—gold in ore. "Locating and realizing on profitable claims of gold-bearing rock such as that of Soledad Mountain… require expert knowledge of mineralogy in the first place and large capital for mining and ore-reduction in the second." Holmes obtained the first through years of experience, and was able to secure the second through perseverance. "The Mojave strike is one for large professional operations; the casual prospector and tenderfoot now flocking to the Silver Queen district are doomed to disappointment," the Times wrote. "Unless they are willing to take their pay in excitement and exercise, they had better stay at home."

Stay at home they did not. Holmes was asked to deliver a talk on December 13 to the monthly meeting of the Mining Association of the Southwest. The subject was to be the gold strike at the Silver Queen. As reported in the Times December 10:

In declining the luncheon invitation Mr. Holmes explained that the recent gold excitement has made it necessary for him to establish a patrol on the premises to keep the public from running over the property. He declared that hundreds of persons are seeking permission to go through the mine, and that he cannot absent himself while it is being sampled by the company which has taken an option to buy it.

Eventually, Holmes sold the Silver Queen, its Extension, and a third claim, the Santa Ana Wedge, on January 11, 1935, to that old firm founded by Cecil Rhodes, Consolidated Gold Fields of South Africa. The price: $3.17 million (plus royalties)—an enormous sum in the middle of the Great Depression. Renamed the Gold Queen, the new owners struck two rich veins, 14 and 30–50 feet wide. In the seven years before World War II halted gold mining in 1942, Gold Fields earned $13 million to $15 million from a million tons of ore.

Fiery Finish

Catlin closes her profile of Holmes with an obituary of the mine, ownership of which reverted to the former owners in 1953 per the original contract, without giving Holmes any gain. The price of gold was frozen at $35 an ounce at about the time he'd sold out. In 1963, he told the Times, "The price would just about have to double to restore things as they were." That didn't happen until 1971, when President Richard Nixon shocked the world by ending the convertibility of the dollar into gold. By that time, Holmes had been dead five years. And his mine had perished as if on a pyre: ignited in November of 1961, a fire burned for two months, consuming most of the timbering of the interior. That fire was eerily reminiscent of the death of Holmes's first wife Hallie who, following the Silver Queen strike, had dreamed of living in Beverly Hills—which apparently was realized. Seven years after that strike, and four years after their divorce, Hallie died in a tourist camp cottage fire near Flagstaff while visiting a relative.

Resurrection

In February of this year, a feasibility study was done for what's being called the Soledad Mountain Project, a conventional open-pit gold and silver mining venture. The operators project a production of about 807,000 ounces of gold and 8.3 million ounces of silver over a period of about 11 years.

Articles, photographs, and legal documents regarding George Holmes and his family are available at FamilySearch.org.

— End June Newsletter • Published 6/2/15 —