Russian Alexandrite by Peter Bancroft

Tokovaya Mines, Ekaterinburg, Russia

Editor’s Note: We are pleased to reprint this selection from Peter Bancroft’s classic book, Gem and Crystal Treasures (1984) Western Enterprises/Mineralogical Record, Fallbrook, CA, 488 pp.

|

One of the best gem mines on earth is the seldom-visited Tokovaya. The little group of mines, located on the Tokovaya River which gently flows into the Pyshma on the Asiatic slope of the Urals, is about 91 kilometers east of Ekaterinburg, as the town was known until the Soviets named it Sverdlovsk [the town has now reverted to its original name]. Factories in and about Sverdlovsk manufacture politically sensitive articles, and visitors are discouraged from entering the region though travel is physically easy. Over the years the Ekaterinburg sector’s pegmatites and metamorphosed zones have been rich in amethyst, aquamarine, blue topaz, quartz, phenakite, chrysoberyl, emerald, and alexandrite. Nearly all gem varieties and species found there occur in fine crystals. Some are exceptional.

By the early 1800s, Ekaterinburg was already a fair-size city on the great road from Russia to Siberia It was named for Empress Catherine II, whose love affairs rated at least equal billing in Ekaterinburg along with stones from the new gem finds. Most of the city’s residents were connected in some way to mining. Russian coins were minted there, and large and efficient lapidary shops constituted a major industry. Cutters were expert at faceting, engraving seals, and carving gemstones. Prices were relatively low and street merchants annoyed visitors with offers of stones for sale.

|

This 1.29-carat Russian alexandrite displays the change-of-color that has made stones from this deposit so famous. From the Mary Murphy collection. Photos ©1988 Tino Hammid, Los Angeles. |

In October 1830, a peasant charcoal-burner was making his way through the forest along the banks of the Tokovaya River when he came upon a large tree felled by a storm. In the exposed roots he found a number of green stones which he took to the gem cutting works in Ekaterinburg, then controlled by Czar Nicholas. The stones were identified as emeralds, and in 1831 the mica-schist deposit was developed as a mine. In many ways the new Tokovaya gemstone deposit geologically resembled the age-old Cleopatra emerald mines at Sikeit in Egypt’s Zabara Mountains, except that the Egyptian mines produced only emerald. Here phenakite, aquamarine, fluorite, apatite, and rutile occurred as well.

|

| Map of Russia. The Russian alexandrite deposit is located about 91 km. east of Ekaterinburg. Illustration © Pala International. |

|

Russian

Alexandrite crystal group. Size: 12 by 7 cm. Locality: Tokovaya mine, Russia Collection: British Museum of Natural History. Photo: Frank Greenaway |

| Russian Alexandrite crystal group. Size: 18 by 13 cm. Collection: Fersman Mineralogical Museum, Moscow Photo: Courtesy Y.L. Orlov |

|

Emeralds from the Urals generally have fine dark green color but are so flawed and interspersed with mica that usable stones are very rare. Emeralds of lighter hue tend to contain fewr flaws. Crystals do not form with the perfection of Colombian emeralds and, therefore, command much less attention. Russian emeralds do come in grand sizes, however. Some crystals reportedly reach dimensions of 40 by 25 centimeters. A choice, rich green emerald crystal in the Fersman Mineralogical Museum vault measures 12 by 8.5 centimeters, and another in the American Museum of Natural History is 11 by 6 centimeters.

|

Czar Alexander II [b. 1818; d. 1881], after whom alexandrite was named. Courtesy: Helmut Leithner |

Czar Nicholas decreed that the imperial lapidary in Ekaterinburg receive the best available gems, cut or carve the gem material, then send finished stones to the palace in St. Petersburg. For some reason, a small collection of the best emeralds seen up to that time did not reach St. Petersburg, but instead arrived in Germany where they were sold to a prince. Some time later, the prince’s wife, wearing her emeralds, visited St. Petersburg. When the Czarina admired the stones the wearer confided that they came from Siberia. Astounded, the empress sent an officer to search the lapidary director’s house in Ekaterinburg. He found several emeralds of great value hidden away and the director was sent to prison.

|

| Tokovaya mine; the earliest known photograph, c. 1890. Courtesy: A. Y. Fersman, Geochemische Migration der Elemente, 1931. Photo provided By: Helmut Leithner |

An entirely new gemstone discovered in Tokovaya’s mica schists had the strange ability to change color under prevailing light. In daylight, rich green colors reflected from its dark background, while at night, under artificial light, it emitted red hues. Ostensibly found on April 23, 1830, the day young Czarevitch Alexander Nicolajevitch came of age, the new gem (a variety of chrysoberyl) created a sensation. It was named “alexandrite” in honor of the youth who would become Czar in 1855 [reigned 1855–1881]. To ensure even greater popularity, alexandrite’s colors of red and green were Russia’s national military colors.

|

Emerald. Size: 11.5 by 6 cm, 2800 carats. Locality: Tokovaya, Russia. Collection: American Museum of Natural History. Photo: Harold & Erica Van Pelt. |

|

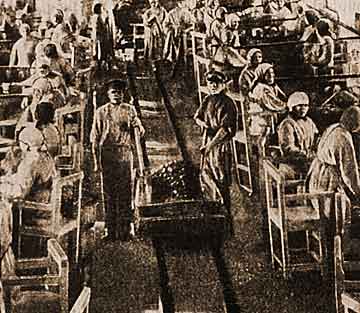

| Factory for sorting and grading emeralds, 1927. Courtesy: A. Y. Fersman |

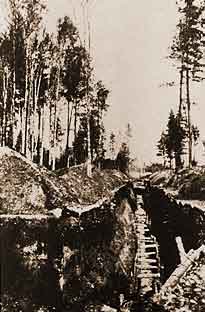

Miners worked the emerald and alexandrite deposits under very primitive conditions. They worked best in spring, summer, and fall, mining known deposits and searching for new ones. But the long, harsh winters with mountainous snowdrifts and biting cold slowed mining activities to a virtual standstill. Most mining occurred in trenches or open pits but small tunnels sometimes followed the narrow veins.

| Gathering water in Tokovaya River to wash gems. Courtesy: A. Y. Fersman |

|

The largest and finest alexandrite crystals ever found are from the Tokovaya deposit. Edwin Streeter wrote in Precious Stones and Gems (1898): “The wonderful alexandrite is an emerald by day and an amethyst at night. Its market value is extremely variable, and sometimes as much as £20 per carat is paid for a fine stone.” In 1980 a gem with the same qualities would be worth many thousands of dollars.

|

| Bridge across the Tokovaya River, c. 1905. Courtesy: A. Y. Fersman |

Unfortunately for the lapidaries, larger crystals, usually highly fractured, yielded little facet-grade material and some crystals would not facet at all. Large (over 3 carats), clean alexandrite gems are among the rarest and most costly of all gemstones. The greatest of all alexandrite specimens known to the author is housed in Moscow’s Fersman Mineralogical Museum. The 18-by-13-centimeter matrix contains at least 22 large alexandrite crystals. The largest, in the specimen’s center, measures more than 6.5 centimeters across. Single crystals have been reported measuring 12 centimeters, but their current location is unknown. Max Bauer in Precious Stones (1896) stated:

Large star-shaped triplet crystals often measure as much as 9 centimeters across, and sometimes even more; one group was found with 22 large crystals and many small ones of the same kind [possibly referring to the Fersman Museum specimen].

Large alexandrite crystals have not been found in modern times, but good alexandrite crystals about 3 centimeters across of gem quality have been found recently.

|

Separato jigs and screens at the Tokovaya. Courtesy: A. Y. Fersman |

| Worked out section of emerald mine. Courtesy. A.Y. Fersman |

|

Palagems.com Note: We have received the following comments from Vitaliy Repej of Ukraine and we provide them to add to the record of alexandrite:

I would like to add value to your perfect site. I am a great specialist in alexandrites. I have read the article by Dr. Peter Bancroft about Russian alexandrite. It is quite interesting and professional. However, there are some misrepresentations. Thus, for the photo of alexandrite crystal group from Fersman museum Dr. Bancroft states group dimension as “18 by 13 cm”. It is not correct because it is measured as 22 by 13 cm and weights 5.38 kg. Then, the article states that alexandrite “Ostensibly found on April 23, 1830” which is also incorrect. The real date of discovery of Uralian alexandrites is presumed to be 3 April 1834 when famous mineralogist Dr. Nordensheld (Finnish by birth working for Russian Tzar) found several crystals in Tokovaya deposits. The name “alexandrite” was officially accepted in 1842 in honor of Russian Tzar Alexandr II.

|

About the author. Dr. Peter Bancroft was Marketing Director of Pala International in the mid-1970s. He is also the author of The World’s Finest Minerals and Crystals and has written for many publications in Europe, Australia and the United States. Dr. Bancroft is a well-known lecturer on mines, minerals and gemstones.

In contrast to many “armchair authors” who merely recycle what has appeared in other books, Dr. Bancroft has spent years traveling the world like a modern-day Herodotus, visiting hundreds of remote and fascinating mineral and gem deposits, and interviewing miners and local inhabitants. Bancroft has uncovered a wide range of information, some of it never before published. This and his extensive knowledge of the literature have combined to produce an authoritative and highly readable text.

Although many fine specimens reside in public collections such as the Smithsonian Institution and the British Museum, Bancroft has searched further through a vast number of private collections worldwide in order to assemble the suite of magnificent photographs found in Gem and Crystal Treasures. Many specimens in these collections are rarely if ever available for public view.

Dr. Bancroft has done graduate work in geology at the University of Southern California, The University of California at Santa Barbara, and at Stanford University. His doctorate, in Education Administration, is from Colorado State University. During his long professional career he has served as teacher, principal, and superintendent of schools in California; as a White House consultant on education, as a professional photographer; as a gemstone buyer, as Curator of Mineralogy at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History; and as Director of Collections for the San Diego Gem and Mineral Society.

His personal mineral and crystal collection has won state and national honors. In 1984 he was selected as an Honorary Awardee for the American Federation of Mineral Societies’ Scholarship Foundation.

Dr. Bancroft’s son, Edward, has a collection that can be seen in the Dept. of Geological Sciences at the University of California at Santa Barbara. A beautiful introduction is online at: The Bancroft Collection.

Today, Peter Bancroft resides with his wife Virginia in Fallbrook, CA. Those wishing to correspond with him can contact him at:

Dr. Peter Bancroft

3538 Oak Cliff Drive

Fallbrook, CA 92028

USA