Peridot by Peter Bancroft

Zabargad Mines (St. John’s Island), Red Sea, Egypt

Editor’s Note: We are pleased to reprint this selection from Peter Bancroft’s classic book, Gem and Crystal Treasures (1984) Western Enterprises/Mineralogical Record, Fallbrook, CA, 488 pp.

|

B

y the dawning of ancient Egypt, swarthy sailors had landed on a tiny island in the Red Sea. Treeless and scorched by a brutal sun, the bleak land offered no food or water–but glittering olive-green crystals lay scattered about the ground. Explorers gathered a few which eventually came to the attention of Egyptian royalty in the capital city of Thebes.

According to Agatharchides in his De Mare Erthraeo, Egyptian kings ordered the discoverers to collect gems and deliver them to the royal gem cutters for polishing. In Naturalis Historia, Pliny tells of the first specimen presented to Berenice, Theban queen of Lower Egypt, about 300 B.C.

First called the Serpent Isle, then the Island of Topazos, followed by St. John’s Island, and currently Zabargad (Arabic for peridot), the oft-named island was systematically worked for hundreds of years, possibly as early as 1500 B.C. by the Pharaohs. Later before the time of Christ, the Ptolemies who ruled Egypt also worked it. Officers of Egyptian courts directed mining activities and used slaves for labor. Workers reportedly died by the hundreds and few ever left the island.

|

| Peridot (gem quality forsterite); Size: faceted stone, 146 carats; largest crystal, 4.5 by 3.5 cm; Locality: Zabargad (St. John’s Island), Red Sea, Egypt; Collection: Institute of Geological Sciences, London; Courtesy: Institute of Geological Sciences; Photo: Martin Polsford |

The green stone was first called topazion, and this name remained until the 18th century when the British began to refer to the gem as peridot. Today, the gem variety of forsterite of the olivine group still bears that name.

|

| View of main peak on Zabargad, 1914; Courtesy: F.W. Moon, Saint John’s Island |

Like other gems, peridot was believed to offer special powers to the wearer. Marbodei mentioned in De Lapidibus that peridot would dispel the terrors of the night: “If it were to be used as a protection from the wiles of evil spirits, the stone had to be pierced and strung on the hair of an ass and then attached to the left arm.” In the Middle Ages, the belief persisted that peridot would dissolve enchantments and put evil spirits to flight.

|

| On the Red Sea with felucca-type said set. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

Although no records survive, significant work must have taken place during the 11th and 12th centuries. Christian crusaders are known to have returned home with large peridots as part of their loot. Fine gems from these mines remain today in a number of European sanctuaries including the Treasury of the Three Magi in Cologne and the Vatican. The precious stone and jewelry collection in the Tower of London also contains large peridot gems.

|

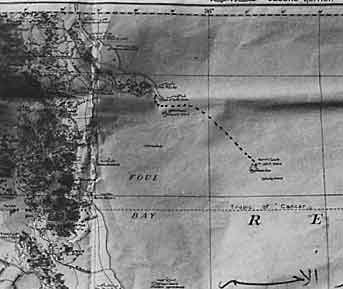

| The map used to plot our course to Zabargad. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

In the early 1900s new peridot crystals began to appear in European mineral collections, and fine faceted stones were once again offered for sale by important jewelers. Turkish rulers of Egypt apparently directed a series of successful mining ventures until 1922, when the Red Sea Mining Company acquired a lease and located new sources of the gem material. Ismalum Bey, managing director of the company, sold history’s largest peridot crystal–actually only a crystal half–to Cairo businessman Max Ismalun. Measuring 6.6 by 5.1 by 2.5 centimeters, the well formed, nearly flawless specimen, as fine deep green color. Ismalun took the crystal to London and sold it for $100 to the British Museum of Natural History, where it may be seen today. The Red Sea Mining Company abandoned its operation with the outbreak of World War II, and since that time the peridot deposit has been worked only sporadically. For the past 20 years, it has been abandoned.

|

| Egyptian skipper, Shasli, checks boat’s engine. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

Mineralogists know that large peridot crystals initially formed in fault cracks–some of them 25 meters deep–which penetrated the basic country rock, peridotite. Poorly attached to crack walls, the crystals may have been loosened by seismic action or weathering, after which they tumbled to the bottom of the fissures where miners found them mixed in the rubble of broken rock. While crystal faces are usually clean and bright, they frequently show fresh fractures, lending credence to the theory that seismic movement damaged them.

|

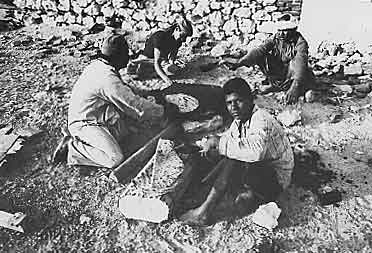

| Ship’s crew comes ashore to make bread. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

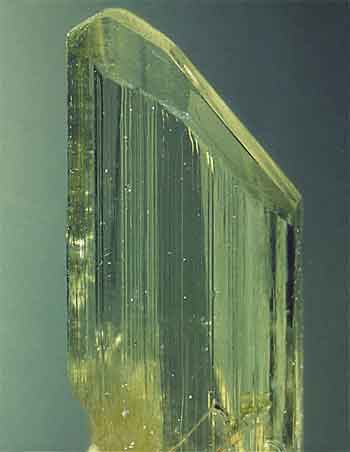

Peridot is found in a number of localities around the world, but large gem crystals are unique to Zabargad. Crystals most often are flattened and tabular in form. Doubly terminated examples are very rare.

|

| Only a few shore birds visit reef-protected beaches on Zabargad. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

It was the author’s good fortune that Swiss gemologist Edward Gübelin shared his enthusiasm for an expedition to Zabargad in 1980. The Egyptian Ministry of Police issued our permits and assigned an officer to accompany us as guide and interpreter. In Cairo we packed a rented car for the 2000-kilometer round trip with 20 gallons of water, 30 extra gallons of gasoline, mining tools, bedding, clothing, cameras, and dehydrated food for at least two weeks. Our route led up the Nile River to Beni Suef, across the Eastern Desert to Za’farana on the Gulf of Suez, and south along the Red Sea to the little port of Ras Banas. There we chartered a felucca (a sailboat of ancient Egyptian design) equipped with a small rusty engine for the 54-kilometer voyage which required seven hours.

|

| Main gem pits near bottom of peridotite hill. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

As we neared Zabargad, the island appeared larger than its 4.5 square kilometers. Hundreds of old dumps clustered about the base of the main peridotite hill, as clearly visible as the few remaining walls of the mine headquarters just above the beach. A long stone pier jutting into the lagoon was in such disrepair that we landed our dingy on the sandy beach.

|

| Zabargad lies dead ahead. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

While the boat’s four-man crew paddled equipment and supplies ashore, we began searching the area. The beach was littered with light bulbs and wooden pallets–even a plastic Brut Cologne bottle–all blown to the island by prevailing winds. The only life appeared to be a few shore birds and clusters of tiny land snails. To avoid the wind we set up our camp within the roofless brick walls of the old mining office. The crew returned to the boat to live on board and we were alone on Zabargad for the following days and nights.

|

| Peridot. Size: 5 millimeters; Self-collected by the author. Photo: Violet Anderson |

The chief peridotite deposits lie on a slope toward the bottom of the largest hill about 1000 meters south of our camp. Rock tailings cover the entire area and most tunnels have been obliterated by dumps. Because these cover even older dumps, it is possible that all of the oldest workings lie beneath newer waste rock. Previous miners had used large screens to sift out crystals from the ore, and a careful search failed to reveal a single large crystal. Overlooked, however, were tiny peridot crystals up to 0.5 centimeters in length which were scattered about a few of the tailings. We collected a score or so of these little crystals–exact microminiatures of the larger crystals seen in museums.

|

| Edward Gübelin at entrance of an old tunnel. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

From our observations it seems evident that because of the great size of the deposit some peridot crystals must have been overlooked and remain in deep fissures underneath the dumps. But a large-scale mining operation on Zabargad would require enormous effort. Potable water would have to be converted from seawater; pumps, wash tables, water lines, and tractors could be landed on the island only at great expense. The problems of establishing a base camp, of recruiting a viable and trustworthy crew, of obtaining official mining rights effectively prohibit a successful mining venture.

|

| Ruins of mining camp on Zabargad built in 19th century. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

The unique moments of our last night on Zabargad will not soon be forgotten. After finishing dinner and a bottle of Cleopatra brand Egyptian wine, we were lying on our sleeping bags and, gazing upward, found ourselves surrounded by countless incredibly bright stars hanging low in the evening sky. Not a sound nor the slightest movement of air disturbed our mood. What was it like 4000 years ago when dark-skinned men slept on the same ground and wondered about the same stars? Perhaps one day Zabargad would support cities and industry; but for now it is still a tiny deserted island, hardly a speck in the vastness of the Red Sea.

|

| View of old peridot workings from camp. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

|

About the author. Dr. Peter Bancroft was Marketing Director of Pala International in the mid-1970s. He is also the author of The World’s Finest Minerals and Crystals and has written for many publications in Europe, Australia and the United States. Dr. Bancroft is a well-known lecturer on mines, minerals and gemstones.

In contrast to many “armchair authors” who merely recycle what has appeared in other books, Dr. Bancroft has spent years traveling the world like a modern-day Herodotus, visiting hundreds of remote and fascinating mineral and gem deposits, and interviewing miners and local inhabitants. Bancroft has uncovered a wide range of information, some of it never before published. This and his extensive knowledge of the literature have combined to produce an authoritative and highly readable text.

Although many fine specimens reside in public collections such as the Smithsonian Institution and the British Museum, Bancroft has searched further through a vast number of private collections worldwide in order to assemble the suite of magnificent photographs found in Gem and Crystal Treasures. Many specimens in these collections are rarely if ever available for public view.

Dr. Bancroft has done graduate work in geology at the University of Southern California, The University of California at Santa Barbara, and at Stanford University. His doctorate, in Education Administration, is from Colorado State University. During his long professional career he has served as teacher, principal, and superintendent of schools in California; as a White House consultant on education, as a professional photographer; as a gemstone buyer, as Curator of Mineralogy at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History; and as Director of Collections for the San Diego Gem and Mineral Society.

His personal mineral and crystal collection has won state and national honors. In 1984 he was selected as an Honorary Awardee for the American Federation of Mineral Societies’ Scholarship Foundation.

Dr. Bancroft’s son, Edward, has a collection that can be seen in the Dept. of Geological Sciences at the University of California at Santa Barbara. A beautiful introduction is online at: The Bancroft Collection.

Today, Peter Bancroft resides with his wife Virginia in Fallbrook, CA. Those wishing to correspond with him can contact him at:

Dr. Peter Bancroft

3538 Oak Cliff Drive

Fallbrook, CA 92028

USA

Palagems.com Peridot Buying Guide

Introduction/Name. Peridot is one of the prettiest of all green gems, occurring in a color that is the epitome of grass green. Interestingly enough, the name topaz may have initially been applied to peridot, for it is found on the island of Topazos (Zabargad) in the Red Sea.

The name peridot is used to describe the gem variety of the forsterite to fayalite olivine series.

|

| Two magnificent examples of peridot. The cut stone at left is an incredible 172.53 cts. Thee crystal at right is equally rare. Both are from Pakistan. Stone: Pala International; crystal: William Larson collection. Photo: Jeff Scovil |

Color. Peridot is ideochromatic, being colored by the ferrous iron that is basic to its composition. The ideal color is a rich grass-green, but some peridot is yellowish green, greenish yellow or brown. The best colors of peridot generally contain about 10–15% of iron.

Lighting. Peridot is not as light dependent as red and blue gems. It tends to look good under all lights.

|

| Two different peridots, illustrating the importance of clarity. The stone at left is heavily included, while that at right has far better clarity. Photo: Robert Weldon |

Clarity. Since peridot is not a particularly expensive stone, eye-clean clarity is the standard. Burmese gems are often marred by small platelet inclusions, which may give some stones a sleepy appearance. The strong birefringence (0.036) of peridot can also give stones a slightly sleepy look. This is most pronounced in large stones (10 cts. plus).

Cut. Only imagination limits the cuts and shapes applied to peridot, with everything from stunning fantasy cuts to tumbled beads being seen. Again, because it is not terribly expensive, cutters can focus on beauty more than weight retention. This means that good cutting, proportions and symmetry are to be expected. Stay away from misshapen native cut gems, unless they are cheap enough to recut to good proportions.

|

| No OSHA in Burma. A peridot miner at Pyaung Gaung, in Burma’s Mogok Stone Tract. Photo: Richard Hughes |

Prices. Peridot ranges in price from about $50–80/ct. for well-cut gems in the 1–2 ct. size, up to as much as $400–450 ct. for large fine gems of top color.

Stone Sizes. Peridot is common in sizes ranging from melee to faceted stones of 10 cts. or more. Fine faceted stones of greater than 300 carats are known, but quite rare.

Sources. Gem peridot has been found in a handful of places around the world. In large sizes (10 cts. plus), Pyaung Gaung in Burma’s Mogok Stone Tract is most important. Faceted gems of hundreds of carats are known from this deposit. In the 1990s, a new deposit from Pakistan’s Suppatt region was discovered, and this material is every bit the equal of that from Burma.

In the US, the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation supplies good material, but this rarely cuts gems above 10 cts. Peridot is also mined in China, Brazil, Australia and Norway, among other places. The historic deposit of Zabargad has not produced at all in decades.

Enhancements. Peridot is not typically enhanced.

|

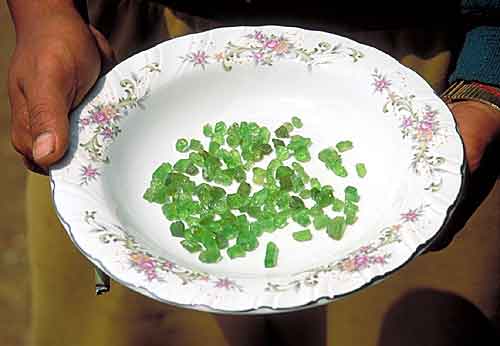

| Rough peridot at Pyaung Gaung, Burma. Photo: Richard Hughes |

Imitations. Peridot has never been synthesized, but a number of imitations exist, including natural stones such as tourmaline, and man-made imitations such as glass. Green glass is the most common imitation, and can be easily separated by its single refraction.

Properties of Peridot

| Composition | Peridot is the gem variety of the olivine group, which has the following species: Forsterite–Mg2SiO4 Fayalite–Fe2SiO4 |

| Hardness (Mohs) | 6.5 to 7 |

| Cleavage | Imperfect to distinct in one direction (rarely seen) |

| Specific Gravity | 3.34 + 0.17,–0.07 |

| Refractive Index | 1.654–1.690 (±0.020) |

| Birefringence | 0.035 to 0.038 |

| Optic Character | Biaxial (positive or negative; the beta index is usually near halfway between alpha and gamma) |

| Crystal System | Orthorhombic; usually occurs as rounded pebbles; well formed crystals are quite rare. |

| Colors | Mainly green; sometimes yellow or brown |

| Pleochroism | Weak to moderate, dichroic |

| UV Fluorescence | Generally inert |

| Dispersion | 0.020 |

| Phenomena | Cat’s eye and star peridot are known, but are rare |

| Handling | Ultrasonic: not safe; never clean peridot ultrasonically Steamer: not safe The best way to care for peridot is to clean it with warm, soapy water. Avoid exposure to heat, acids and rapid temperature changes. |

| Enhancements | Peridot is not typically enhanced. |

| Synthetic available? | No |