Burma, The Mineral Utopia

By Martin L. Ehrmann, Certified Gemologist

The following three-part article was published in the August, October (this part) and December editions of The Lapidary Journal in 1957.

Introduction by The Lapidary Journal

We present herewith the second installment in a three-part series on Burma and its gem mines by one of America’s leading gem authorities, internationally known for his work in the coloring of diamonds by cyclotronic bombardment. The author is now on an extensive gem buying trip in Burma and his gem travels have taken him all over the world many times. Ehrmann was co-author, with Herbert P. Whitlock, in the writing of the book The Story of Jade.

Part Two

|

Most mine owners and miners are interested only in the precious rubies, sapphires and spinels because of the ready market for them. Consequently, the other gems are sadly neglected. If Mr. A. C. D. Pain, a very competent gemologist living in Mogok for many years, had not shown a constant interest in the rarer gems, they would have been ignored as worthless. The following gemstones are found in almost all the Mogok area: peridots, which will be described more fully later; danburites, fine, yellow gems up to forty carats; scapolite cat’s eyes in white, blue and pink of various sizes up to fifty carats; apatites in blue and green, as well as the chatoyant variety which is rather common; albite cat’s eyes up to fifty carats and really plentiful; topazes; and orthoclases and other varieties of the feldspars. Less abundant minerals in the same area are: kornerupines, sphenes, diopsides, iolites, chrysoberyls, zircons and, occasionally, a new gem mineral. Mr. Pain has recently found a new species which is now being described by the British Museum of Natural History in London.

Mr. Pain owns a magnificent collection of representative Burmese gems which he is continually improving in quality. When I saw it last, it contained some two hundred and fifty gems varying in size from two to one hundred and fifty carats. The outstanding stones are a blue kornerupine weighing about twenty carats, a sphene of similar size, a pink scapolite cat’s eye also approximately twenty carats in weight, and a fibrolite of most unusual size. Unfortunately, all my efforts in trying to purchase this collection failed.

In Sakhangy, twelve miles southeast of Mogok, quartz and topaz crystals are found in highly decomposed pegmatite. Because of excessively heavy rains in the past few years, this deposit has caved in completely. The topazes are of various colors and well-crystallized, not unlike those found in Brazil. However, the fine golden colors desirable for jewelry purposes are rare.

For a long time, peridots of commercial gem quality were believed to have come only from St. Johns Island in the Red Sea in Egypt. However, there is a more important locality for this beautiful gem mineral in a village called Pyaung Gaung, eight miles northwest of Mogok. The natives call these peridots Pyaung Gaung Zein (zein means stone). No investigation could be made there as this territory is completely in the hands of insurgents. Several unusually fine, large specimens of these crystallized peridots were purchased and are now in some of our museum collections. The quality of the Burmese peridots is similar to that found in the Red Sea, but the largest stones of pure gem quality come from Burma.

In addition to rubies and sapphires, other important gem minerals mined in Burma include jadeite. Burma is just about the only source of good jadeite in the world. This gem mineral deserves its own chapter later.

Burma is also rich in strategic materials. The tin mines in Tennarim Peninsula are very important. This peninsula is in the southern-most part of Burma and has a coastline of about one thousand miles, connecting in the south with the Malay Peninsula. Tungsten is also mined in large quantities on the Tennarim Peninsula.

In the central and northern part of Burma are many deposits of tin, tungsten, lead, silver and copper, suited for mining. Because of lack of transportation, difficult terrain, and insurgent activities, development of these mines has been most inadequate. There are also a few rich oil fields in the central part, providing sufficient gasoline for Burmese consumption.

Other Burmese minerals worth mentioning are antimony, asbestos, barite, bismuth, chromite, gypsum, graphite, manganese, molybdenum and monazite. There are visible signs that all these deposits are being presently surveyed by private and government geologists, evidencing a purposeful movement to develop all the natural resources of Burma.

|

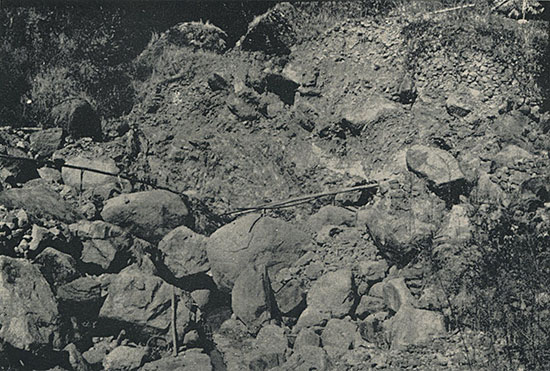

| Alluvial diggings in the Burma gem mines, usually operated by two men. This image, in color, also is included in Ruby Mines of Mogok – Slide Show (image #11). |

History

Stone axes, chisels made of crude rocks, many types of spears, and stone arrowheads indicate that Mogok was first settled by man about 3000 B.C., as such implements were used by the Mongolians who were the first settlers.

Modern Mogok was founded in 579 A.D. when it was all jungles and thick forests. While hunting in the jungles, head-hunters of the Sab Bwa of Momeik lost their way and slept under a tree. At daybreak, they heard birds singing and hovering over them. While investigating the commotion of the birds, they ran into a mountain-break full of beautiful red rubies. They picked as much as they could carry and brought it to the Sab Bwa. He realized the wealth of the area and sent some of his household to establish Mogok. It was first called Thahpainpin Pomegranate for the fruit growing abundantly there; and such a little village still exists on the extreme west limits of Mogok.

In those days, Burma was ruled by a king named Avaking. The capital was the city of Ava, near the present site of Mandalay. After hearing about the fabulous wealth, the king started to invade the area. Then the Sab Bwa of Momeik reached an agreement with King Avaking establishing Mogok as part of Burma in return for twelve specified villages. It is on record that in 1254, a pact was signed by King Ava and the Sab Bwa of Momeik settling all their differences. The Mogok area now became part of the Burma Kingdom, and gem trading began. History has it that no mining operations were first required as the gems were found everywhere.

According to legend, an agent of King Mindon named U Tun Pe Hland showed a ruby called the Ngumauk Ruby to a French trade-mission, telling them that quantities of such valuable stones were to be found in Mogok. At that time, France controlled Siam and now wanted to purchase the entire Mogok area from King Mindon. The members of the trade-mission were especially impressed when the Ngaumauk Ruby was placed in a pan of water and the water turned red, the color of the ruby. King Mindon flatly refused to sell, saying there was not enough money in the world to buy this fabulous area. The ruby itself is said to have become part of the famous British Crown Jewels. Although there was no description as to weight, subsequent accounts made it a very large stone, probably the famous one in the crown jewel collection that was tested and found to be spinel a few years ago.

In 1886, the British government occupied Burma. After victorious battle in the Mogok area, Major Charles Barnard and his troops took over. Barnard Village, where peridots are found, is still in existence. On March 29, 1888, the area was formed as the Mogok Ruby Mines District and Mr. G. M. S. Carter became its first administrator. Distinct from other areas, it was ruled as a separate entity and controlled solely by the British. Mr. A. R. Godbar was the last administrator in 1920.

In 1889, the Ruby Mine Syndicate, Ltd., was formed, capitalized by numerous English bankers and industrialists. It was handled by the management firm of Streeter and Company in London. According to agreement, this company paid the British Crown 40,000 rupees yearly plus one-sixth of all profits accumulated. Barrington Brow M.P. was sent from England to negotiate the first five-year contract which expired in 1893.

Scientific mining began and several geologists were sent to survey the Mogok area. They reported that the bulk of the gem-bearing gravel was located in the center of town where most of the natives lived. The company negotiated with the owners of these properties and bought all the huts located in the surveyed gem-bearing gravel beds. The natives were given new homes or, where possible, old homes were moved to new locations hacked out in nearby jungles. These moves presented no problems as the natives were well-compensated and were promised employment.

Mining began immediately after the people were moved. Electricity was brought to Mogok with the construction of a power plant. Digging began and several millions of dollars worth of rubies, sapphires, spinels and other gems were mined. A single ruby of fabulous size, purportedly worth one hundred thousand dollars, a lot of money in those days, was discovered. Profits were good for the first contract; the company and townspeople were happy with the new way of life.

As the contract had expired, in 1896 the company negotiated again with the British government and agreed to pay a tax of 3,150,000 Kyats (about $800,000) plus one-fifth of the total profits for fourteen years. This contract included all the mines within a radius of ten miles of Mogok. Those were the boom days with everyone working and much money in circulation.

|

| Phenakite on matrix from Burma. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

In 1906, the company extended its mining operations to other areas and bought all the property in the city limits of Mogok, again moving homes to new sites. The original Mogok area is today the site of a beautiful lake in the center of town. Also, about 1906, a ruby was found weighing forty-two carats, of finest pigeon-blood red. After cutting, the ruby weighing twenty-two carats was purchased by an Indian gem dealer, M. Chodilla, for 300,000 Kyats (over $100,000).

Because of heavy rainfall and much excavating, pumping became a serious problem. The hole would fill and stop all mining operations during the rainy season. Experts from London solved the water problem by building tunnels for the water to flow off from the hole. However, this proved to be only a temporary solution. Tunnels costing $200,000 were built into the mountains; but after a year, the same problem arose.

In 1914, affairs of the company began changing rapidly for the worse. Because of stealing, technical problems and wide extensions, large sums of money were lost. Operations were continued, however, until 1922, the expiration date of the contract, marking cessation of company operation. Some personnel remained until 1928, working privately with local people on a half-share basis. On August 28, 1928, this group attempted to remove the water from big tunnels in order to empty the big hole. That venture culminated in disaster as the mountainside caved in. Nevertheless, gem mining continued.

Before the beginning of World War I, an Englishman named Albert Ramsay had settled in Mogok as a lapidary and dealer in rough gems. His alert and inventive mind eventually made him the saviour of the mining industry in Mogok. In previous years, only the clear rubies, sapphires and spinels had been sought. Such stones were not too plentiful, especially those of faceting quality. Mr. Ramsay began experimenting with opaque varieties of rubies and sapphires and found that by cutting them perpendicularly to the crystal axis, a star was formed. Heretofore, such material had been ignored as having no market value. After his discovery of the star, Mr. Ramsay began buying all the material he could obtain and cut it into cabochons showing wonderful stars. It took him a long time to convince the jewelers of Europe and America that this type of stone would gain favor with the gem-loving public; but he finally succeeded and mining was revived in Mogok. Mr. Ramsay also continued in the rough gem business and purchased a gem sapphire weighing 1029 carats in May, 1929, for $30,000. Thirty-two pieces were cut from it, one of which brought the total amount paid for the original stone.

Because of pressure brought by the local people, new rules and regulations were made in 1930 when homesteading of mines began. Claims were made by individuals and granted by the Crown. The tax levy was 10 rupees per miner employed. By this time, all company holdings had been abolished and the machinery and electric plant were sold to Mr. Morgan and Mr. Nichols. Mr. Morgan has since died, but Mr. Nichols still carries on, supplying electricity to the whole area. Secrecy surrounding all operations makes it impossible to determine the total output of gems.

On May 7th, 1942, Mogok was invaded by the Japanese and all mining stopped. Miners dug holes in their backyards and under their homes and discovered many gems. On March 15, 1945, the British army moved in and the Japanese withdrew. The independence of Burma from British rule was declared on January 5, 1948. Mining continues in the same primitive manner, but about twelve-hundred mines are now owned individually. Some are just two- to three-men operations while others employ up to fifty men. All miners are shareholders and split the profits with the owners, thus largely eliminating high-grading.

The Jade Mines

Jade and amber occur in the northernmost part of Upper Burma, reached by a weekly flight from Rangoon to Myitkyina. This village is in the eastern part of the so-called jade and amber belt and is very near the border of Yunan Province of China. Mogaung, about fifty miles to the northeast from Myitkyina, is the last city in Burma with a railroad. The center of the jade and amber mining district is the village of Mogaung where the largest deposits are found within a radius of seventy-five miles in all directions.

The jade mines of northern Burma contain the most important deposits of this interesting material in the world. The early Chinese prized it greatly and are said to have believed that jade possessed magical qualities which made it a sacred stone. Three thousand years ago, jade from this area was brought via the caravan route to the center of China. Members of the Imperial family and nobility of the Chou Dynasty wore ornaments of delicately carved jade. Weapons of war such as swords, sabres, spears and knives were also fashioned from this precious stone. Jade was even buried with the dead in the belief that it would ward off evil spirits. It is no wonder, then, that all the jade mined in this area found its way to China. At a later date its wonderful qualities, such as color and durability, became known in the Western Hemisphere and the demand increased greatly.

The jadeite region is almost inaccessible most of the year. During the monsoon season, it is practically impossible to reach it as it is a highly dissected upland region consisting of ranges of mountains which form the Chindwin-Irrawaddy Watershed. It is higher in the north than in the south and Tawman, one of the principal jade-mining districts, is situated on a plateau about three thousand feet above sea level. The highest mountain is Loimye, about a mile above sea level. Tawman is about sixty-five miles from Mogaung. There is a road which is barely passable even under the best conditions, so the most satisfactory mode of transportation, if not the fastest, is by mule truck. These conditions are serious handicaps in any attempt to complete a geological survey of the area.

Jade mining progresses for only three months of the year, from March to May. All mining activities cease with the coming of the rainy season, since the shafts fill with water within a few days.

|

| Typical jadeite mine in the Mogaung area of Burma. |

Many workings were observed by the author who considered them all of similar nature: At the top, there is a very thick over-burden of red earth, probably the weathering of serpentinized peridotites that form the rock into which the jadeite albite mass is intrusive. Below the serpentinized peridotites lies a thin, earthy, very light chlorite schist locally called “byindone.” Below it is an amphibole schist, or amphibolite. Next to that is an amphibole-albitite rock which is underlain by albitite and it, in turn, is underlain by jadeite.

The mining methods today are still the same as those used a thousand years ago, except that hydraulic drills are now being used in some areas. Before any jade mining is begun, every worker, whether Kachin, Shan, Burman or Chinese, prays to the jade spirits, or Nates, in the belief that they will discover valuable jade quickly the Nates are pleased. Generally, the overburden is quarried with picks and crowbars until a steep face is obtained. Water is dammed upstream to make it flow over the steep face, washing away all earth and leaving the boulders clearly exposed for examination. It is well to remember that the selection of the locality and all the work are started through pure instinct, an inner conviction of the miners rather than any scientific reasoning. When the valuable jade is discovered in one spot, all the miners flock to it and work it until all the jade has been removed. Consequently, they frequently forget where they had worked last and begin digging in spots previously mined, with much labor thus lost. Scientific mapping and a coordinated, well-organized mining program would certainly yield large amounts of fine jade in this area at a small percentage of the present cost to the jade merchants, who do almost all the financing.

The Mogok valley is about twenty miles long and two miles wide. In the center of the village of Mogok is located a beautiful lake created by digging for precious stones during the Ruby Syndicate era. The Mogok gem area reaches to the city of Momeik, a distance of thirty miles to the North and sixty miles to the West, up to the villages of Twingwe and Thabeikian on the Irrawaddy River.

There is a valuation committee in every jade mine. When a piece of jade is found, the financier has it evaluated by this committee, which receives a fee of 5% of the value. As a rule, such valuations are very low. If the financier decides to keep the jade, the miners receive half of the evaluated price. 10% more goes to the local government under whose jurisdiction the stone is found. Values and evaluations are never mentioned but merely indicated among the interested parties by the conventional finger pressures under a handkerchief. It is costly to ship the jade boulders to Mogaung, the chief trading center. Sometimes, as many as fifty coolies are employed to transport a boulder weighing a ton. They proceed very slowly through the rugged terrain until they reach a place where the jade can be placed in an oxcart and brought to Mogaung. There, the Government again collects 33 1/3% of the value before the merchant is permitted to ship his jade out of Burma.

|

| Peridot crystal from Mogok, 4.3 cm high. Bill Larson Collection. (Photo: Jeff Scovil) |

Up to this point, the value is merely a fictitious figure without any actual basis. The main thought is to have as low an evaluation as possible until all government taxes are paid. Then the jades are prepared for local auctions and for export in the following manner. Each boulder is weighed and a seal is placed upon it. At strategic points, cuts of approximately 3/4" in width and 1/2" in depth are made in each boulder and polished to show the color. The Chinese jade dealers pride themselves on being able to determine the value of each jade boulder by the appearance of the polished cut. On certain days, auction sales are held for the prospective purchasers.

The auctions differ greatly from ours, since there is no audible competitive bidding. The purchaser accompanies the auctioneer along the path on which the boulders are displayed. A stop is made before each numbered boulder in which the purchaser expresses interest. With his hand and the auctioneer’s hand covered by a cloth, the bidder makes his offer by pressure on the auctioneer’s fingers, thus insuring absolute secrecy in each transaction. In the evening, the sales are completed and the boulders turned over to the highest bidders.

It is not unusual for many boulders to remain unsold during these auctions. They are then shipped to dealers in Hong Kong for similar auction sales. From a scientific point of view, it is a real gamble to buy jade in this manner. The purchasers are actually gamblers rather than jade experts. Much money has been lost by these superficial methods of purchasing.

All jades leaving Burma are shipped from Mogaung after clearance by the Government agency. Boulders of jadeite are wrapped in a heavy, dark sailcloth tied with hemp rope and shipped by Irrawaddy River boats to Rangoon, where they are put on boats going to Hong Kong. Also, a considerable quantity is smuggled across the border to Yunan, Communist-controlled China, by mules. Prior to the Communist occupation of China, jade was shipped to Canton, Shanghai and Peiping. Approximately 15% of all jades, the poorest quality, remains in Burma and is usually sold in Mandalay, where there are many jade cutters and jewelry manufacturers.