![]()

The Sickler Family:

Historic San Diego County Gemstone Miners

By Peter Bancroft

Part III of IV originally published in The Wrangler, a quarterly published by the

San Diego Corral of The Westerners, Vol. 29, No. 1, 1996, pp. 1, 3–8

Access Part I here

Access Part II here

Part III of IV

The Chinese Connection

But at about the same time [as the emergence of a domestic market], a new market for tourmaline was developing in China. The Empress Dowager, Tz’u Hsi (pronounced “too shee”), was known to have a passion for gemstones, particularly favoring green Imperial jade and pink tourmaline. Due to her considerable influence, both gems became immensely popular throughout China. As the Chinese market for pink tourmaline expanded, a handful of enterprising Chinese in San Diego began to buy tourmaline for export to China.

|

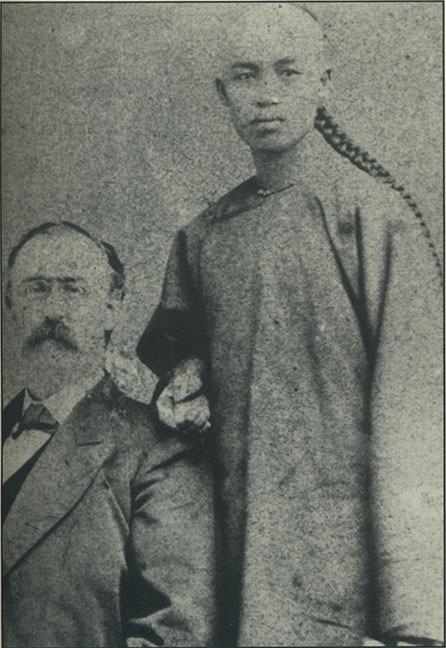

| Ah Quin, as a young man, 1873, with employer in Santa Barbara. |

Hom Bing, one of those merchants, sought large tourmaline crystals of a deep rose color. To be suitable for his purposes, the crystals could be flawed but must be without cracks. Finding a dealer with a quantity of the material he desired, Bing was quoted as saying in the quaint speech of the time: “I give you twenty dollar a pound and you sell me all the stone you get like that.” Bing carefully packed his crystals in wooden boxes and shipped them to his father in China where they were to be carved into figurines, snuff bottles, and beads for jewelry.

Members of San Diego’s Ah Quin family seem to have been buying tourmaline as early as 1898. Family patriarch, Ah Quin, had arrived in San Francisco in 1868, having taken a $50 ship passage from Canton, China. For twelve years he worked at odd jobs in Santa Barbara, San Francisco, and Coal Harbor in Alaska. Deciding that he wanted to enter the mainstream of America, he cut off his queue while in Alaska, returned to Santa Barbara, explored job opportunities in San Francisco, Stockton, and San Diego, and eventually settled on San Diego as offering the best opportunities.

In 1880, Ah Quin opened a general store featuring Oriental imports in San Diego’s Chinatown in the Stingaree District. His first store was on Fifth Street between I and J. Two years later he moved to what was to be his permanent location on Third Street. In 1881, with his store business operating smoothly and his reputation as a reliable businessman assured, he was employed by the California Southern Railroad to hire gangs of Chinese laborers to build a 196-mile railway from National City in south San Diego County to Barstow in San Bernardino County. The most difficult section of the road proved to be the rocky Temecula Canyon area where more than a thousand Chinese were on the job.

On December 14, 1881, Ah Quin brought to San Diego his new bride whom he had met while living in San Francisco, nineteen-year-old Sue Leong, a ward of the Chinese Presbyterian Mission in that city. By 1900, they had twelve children.

|

| Ah Quin and Bride, Sue Leong. Courtesy Georgia Quin Ung. |

Ah Quin remained involved with the California Southern Railroad construction until 1885, meanwhile developing his merchandising business and acquiring real estate holdings. Supplying the railroad had prompted him to become involved in growing food crops locally, as well as importing food and other supplies from outside sources. His properties in both the city and county included farm land on San Miguel Mountain and in National City and Bonita. The Bonita farm in the Sweetwater River valley grew potatoes. He also owned land in the Los Angeles and Bernardino areas. Among his other business ventures, this much respected “Mayor of Chinatown” was a regular buyer of M. M. Sickler’s tourmaline, which he shipped to contacts in China.

|

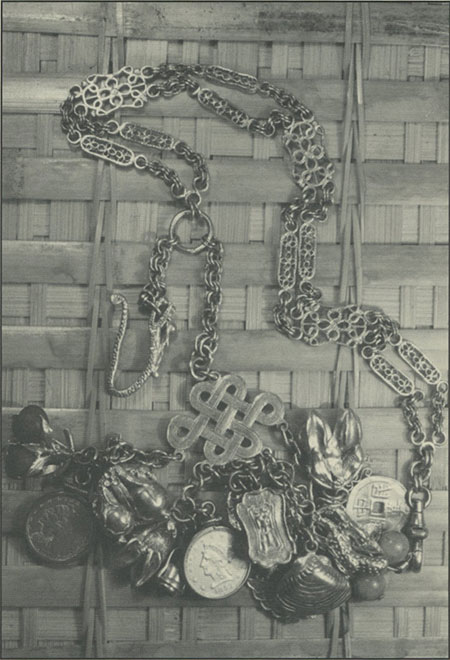

| Never before published picture of Ah Quin’s personal gold necklace. Courtesy Dr. Tom Kong. Photo: Peter Bancroft. |

Ah Quin died in a fatal accident in 1914 at age 66 and was given a Christian burial with six American and six Chinese pallbearers. Ah Quin had seen to it that all of his five sons were exposed to the many facets of his business activities. As it turned out, the second oldest and second youngest sons became closely involved with San Diego County gemstone mining. Ah Quin, while living in Santa Barbara, had picked up the fundamentals of gemstone cutting and assaying from James Shedd, an assayer. Quin had tried to interest his second son, Thomas (Tom) Quin, in learning the gem cutting art from Fred Rynerson, an experienced gem cutter and friend of the Quin family. Tom had no interest in lapidary work, but saw there was lots of profit to be made in selling tourmaline. The second youngest son, Henry Quin however, had studied mining engineering at the University of Southern California. Tom and Henry joined with Fred Rynerson in acquiring a fifty-year lease on the Himalaya mine at Mesa Grande.

|

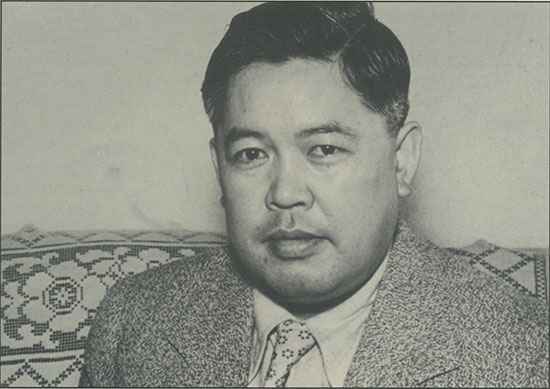

| Thomas Quin, age 20. Courtesy Dr. Tom Kong, Ventura, California. |

The Quins immediately hired twenty-five Chinese laborers to work the mine. Unfortunately some of the miners belonged to the Chee Kung Tong whose sworn obligation was to overthrow the Ching Dynasty. Fights and knifngs were common, making it necessary to rotate the work force in order to reduce violence. Little is known if the Quin brothers’ Himalaya venture was a success. In later years, however, Tom operated lotteries in California’s Central Valley, much to the chagrin of the Quin family, and he was known to offer a tourmaline crystal as a special premium to a lottery winner. Tom eventually became the most prominent and influential of the sons of Ah Quin and inherited his honorary title of “Mayor” of Chinatown. He died in 1937 at age 49.

|

| The Ah Quin Family in 1899: Back row left to right, Tom, Annie, Mamie, George; middle row, Maggie, Franklin, Sue Quin, Ah Quin, Lily; front row, Minnie, McKinley (in Sue’s lap), Mable, Henry, and Mary. Identifications by Murray K. Lee. |

It was the author’s great pleasure some years ago to meet briefly with Thomas Quin’s daughter, Georgia Quin Ung. At 80 she was a smart, articulate, and very beautiful lady, sadly now deceased. She provided some of the Ah Quin family photographs used as illustrations in this article.

|

| Thomas Quin, age 45. Now unofficial “Mayor” of Chinatown. Courtesy Dr. Tom Kong, Ventura, California, |

Upon the Dowager’s death in 1908, the intense Chinese interest in tourmaline diminished to the point that the world market for the gemstone practically collapsed. By 1915, tourmaline production in San Diego County was nearly at a standstill.

Marion Sickler’s Later Career

Over and above his gemstone mining activities, Marion Sickler had been a busy man in the late 1890s and early 1900s. In addition to operating his grist mill, he was appointed Pala’s Justice of the Peace in 1890. Somehow, M. M. became involved in a feud over water rights and was shot in the leg by a man from the Agua Tibia Ranch, San Diego. The affair was finally mediated by attorney Col. Ed Fletcher.

In the early 1900s, M. M. contracted with juvenile authorities of San Diego County to raise orphan boys. The boys were sent to the Pala school and, during vacation times, earned their keep as helpers in the mines. One such helper, Francisco Moreno, married a Sioux “Indian princess” named Mary, who was frequently invited to display her collection of Indian artifacts at the San Diego County Fair and elsewhere.

In 1916, the San Luis Rey River flooded, destroying M. M.’s flour mill. Two of the millstones were later found downstream near the Pala Mission. Only the mill’s foundation remains today, and is a feature attraction of the Wilderness Gardens Preserve.

For many years, M. M.’s wife, Lila Curtis, taught in the one-room schoolhouse at Pala. When the school population shifted, the schoolhouse was put on skids and moved to where it was most needed. One year, the river cut its banks, flooded the valley, and isolated the school. Lila got the children out safely but decided to remain with the school building. After she had settled down for the night, she was startled by a face peering in through the window. The frightened woman finally realized that it was an old Indian who only wanted to help and had brought some food for her.

Marion M. Sickler died in 1940 at the age of 92 and was buried in the Episcopal cemetery at San Luis Rey. He was San Diego County’s oldest Mason.

Fred M. Sickler, Sr., Discoverer of Kunzite

Marion’s son, Frederick Marcellus Sickler, Sr. was born on July 12, 1879, in a private dwelling at the corner of Broadway and Twelfth St., the current site of the San Diego Post Office. He attended elementary school at Pala and then left home to study at Russ High School in San Diego. He lived in the house of his step-grandfather, George Hazzard, who rode a horse all over town drumming up business for a general merchandise store situated at Fifth and Market streets.

After graduation, Fred returned to Pala, where he and his brother, Allan, discovered the White Queen mine. A year later, his father (M. M.) had staked out the Katerina mine. Both prospects produced slender, striated, lilac-colored crystals that were easily cleaved along the vertical axis. Fred knew of no other gemstone with similar characteristics. He showed his unidentified crystals to miners at Mesa Grande and to jewelers in San Diego and Los Angeles. No one had the slightest idea of what they were.

|

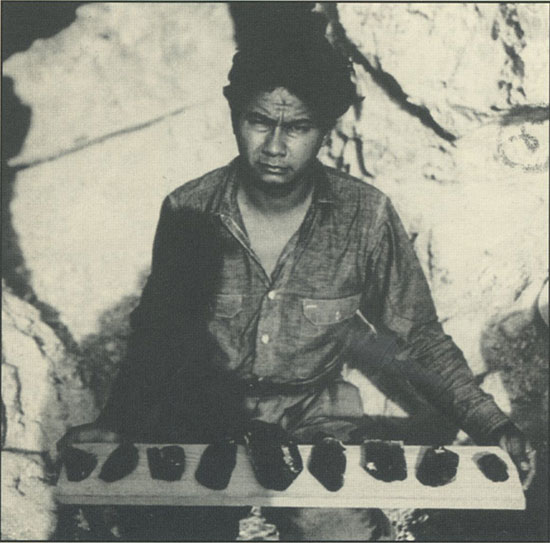

| George Ashley’s Mexican helper with high quality kunzite from Katarina mine (ca. 1950s). Photo by George Ashley. |

Finally, in December 1902, Fred sent a crystal to Tiffany, New York’s premier jewelry firm. Dr. George F. Kunz, staff gem specialist, immediately determined that the crystal belonged to the spodumene family, and was a gemstone new to science. Kunz published his findings in the September 1903 issues of several American scientific journals. To honor his work, the new gemstone was officially called kunzite. Tiffany bought thirty of the largest and best-colored kunzite crystals from Fred, cut and faceted them into desirable shapes, and set the finished stones in jewelry. They were the first kunzite gems to be brought before the public.

But Fred Sickler, Sr., was restless. He hoped to continue his luck, and thus began to travel in hope of finding new kunzite or other gem deposits. He visited all major San Diego County gem mines without success. He moved on to Arizona, where he ran out of money. Once, lost in the desert, he nearly died before an Indian found him wandering aimlessly about. While he was recuperating, Fred learned that the Indian wanted him to marry his daughter. Fred took off in a hurry, headed toward some distant mountains, and arrived at a little town during a snowstorm.

Badly needing a drink to combat the cold, he entered the nearest saloon. Groups of miners and sheepherders were playing poker. Never the best of friends, the two factions got into a full-scale brawl. The first shot blew out the lamp, and the shooting continued in the dark. When things settled down, two sheepherders were found dead. Fred decided that it was time to return to California.

Hiring on with the Pacific Coast Borax Company in Death Valley as a prospector, he searched for new borax deposits. “On one trip,” Sickler recalled, “we camped at Saratoga Springs, at the south end of Death Valley. In the morning, a teamster asked if I had seen any ghosts. ‘No ghosts,’ I replied. ‘Well, you were sleeping on the grave of the teamster young Wassum killed.”

It seems that the teamster and his swamper, “Wassum,” quarreled after stopping for the night. During a fight, Wassum killed the teamster with a shovel and buried him on the spot. The swamper was unable to manage the team, letting the mules run away. Out of control, the wagons overturned, breaking Wassum’s leg. But he was able to mount a mule and return to the Borax works, where he reported that the teamster had been killed in the accident. The foreman took his word for it and the case was closed.

Later, Wassum confessed to his father, the teamster was exhumed, and his skull was found to be cleanly cut through, as ifby a shovel. The boy was eventually freed, primarily because neither the coroner nor the district attorney wished to undertake the long, dangerous trip to Death Valley to investigate. Fred Sickler was particularly interested in the killing because the swamper had come from Pala, and Fred had heard the story as a child.

|

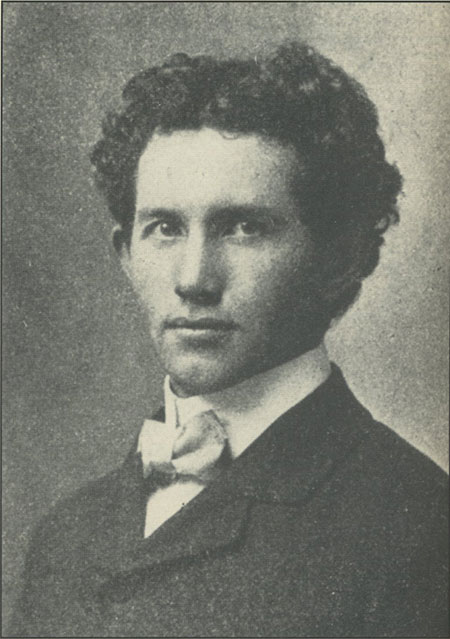

| Fred M. Sickler, Sr., as a young man. |

Next, Fred went to work as a chemist for a sugar beet factory in the San Joaquin Valley; but, wishing to see more of the world, he borrowed money from W. A. Sickler and started on a world-wide trip. First, he went to Egypt, then north into Germany, where he studied mineralogy and mathematics at the University of Heidelberg. Eventually, he traveled on to Kiel, where the German training cruiser Emden was berthed. He made friends with the crew and, years later when the ship visited San Diego, Fred was invited to an old-fashioned beer party on board.

His travels took him to the Holy Land, Egypt, Dakar, and South Africa, where he found himself in the middle of the Boer War. South Africans thought he was a professional spy and wanted him to join their army. It was time to move on again!

Broke and without employment, he ended up in Panama.

By then, Fred was fluent in Spanish, German, French, and English, which enabled him to get a court reporter’s job in Panama City. The man who hired him later became President of Panama. Fred was invited to the President’s inauguration, but by that time he was in Alaska.

Leaving Panama, Fred traveled north into Mexico. He particularly liked the quaint historic city of Guadalajara. It was there that he saw a number of bandits lined up against an adobe wall and executed. Later in the day, he pried bullets from the wall as souvenirs.

The Wonderlust Continues

Still footloose and lonely, Fred decided to travel east to see what was left of the family house in Falls, Pennsylvania. Nothing of the building remained, but after much sleuthing he found the graves of his grandparents in an overgrown cemetery. He liked the Pennsylvania countryside but could not stand its cities. He recalled that while in Pittsburgh he “couldn’t make a white shirt last more than one day because of the smoke.” Continuing on to Washington, D. C., he took in the sights of the nation’s capital.

Fred had a reputation as a hearty eater and, on occasion, could put away three or four helpings at a time. While in Washington, he met a woman and invited her to dinner. Fred ordered a dozen Chesapeake oysters for himself and managed to finish them off in front of his amazed companion. Fred liked Eastern dishes but missed home-cooked Western food. On one occasion, he wrote to his dad: “Please send me some chili beans.”

While thoroughly enjoying his travel adventures, he decided he needed more formal education and enrolled in Carnegie Technical University at Pittsburgh with majors in mathematics and chemistry. Fred proved to be an exceptional student at Carnegie. He was graduated as valedictorian of his class with fluency in seven languages. He was offered a teaching chair at the university, but that he perceived as being too restrictive and decided that he would be unhappy with what he considered sedative university life. Instead, he enrolled at Bliss Electrical Institute in Pennsylvania, later graduating as an electrical engineer.

|

| Prize kunzite specimens, ranging in size from four to fourteen inches in length. Courtesy San Diego Historical Society, Ticor Collection. |

Access Part IV here.