Longido Ruby

As described by Edward R. Swoboda

In 1949, two English prospectors, residents of Kenya for many years and with great practical experience in traveling the wilder, more primitive sections of that country, were systematically examining a range of dry low hills that formed part of the planalto of the Masai tribal nation, bordering the giant upthrust of spectacular Mount Kilimanjaro.

A narrow dirt track winding through the hills afforded them vantage spots where they could drive their truck off the road to approach more closely, likely looking formations that could contain the minerals or gems they were looking for.

By the end of their second week of long hikes, made daily from the starting point of their truck at various stops, and closely examining surface outcrops and checking for the float material that had eroded down-canyon from the outcrops, they had not turned up anything of real value and their enthusiasm in this hot, dry work was fast diminishing.

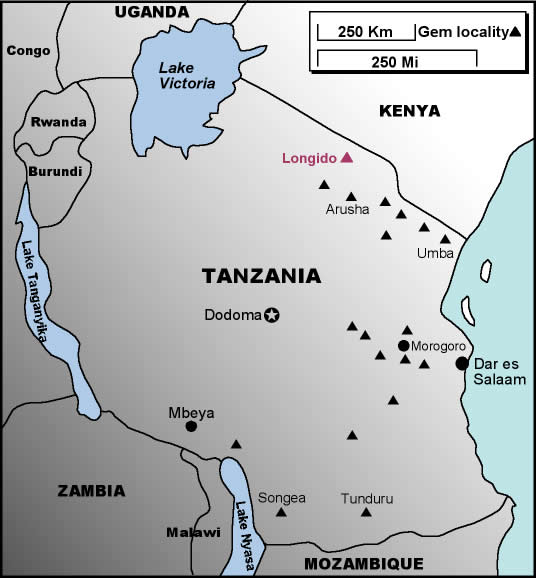

|

| A fine Longido (Tanzania) ruby cabochon flanked by Longido ruby crystals in a green zoisite matrix. Photo courtesy of Edward Swoboda. |

Then late one afternoon, Tom Blevins, one of the two partners, made a remarkable discovery. While walking up a gentle rise and searching the open spaces between the clumps of dry grass and the thorn bushes for float minerals, he came upon a small flat sink, devoid of plants, and extending for several yards to the base of an outcrop of green stone. Contained within this small basin was what he later described as the most electrifying and exciting view that he had ever experienced in all his years of prospecting in Africa. Covering the sides and the bottom of the basin was a breathtaking display of flat, sharp-faced, hexagonal, deep red ruby crystals.

|

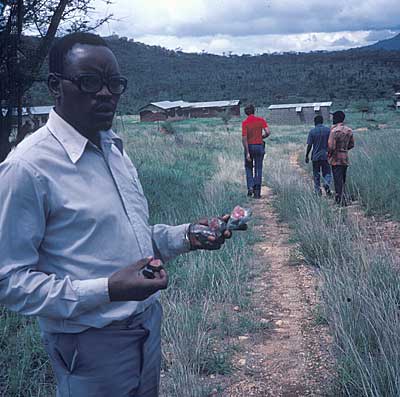

| Map of Tanzania, showing the location of the Longido ruby mines. Illustration © R.W. Hughes |

He was soon on his knees, picking up the fragments and the loose crystals, some of which measured up to two inches and weighing hundreds of carats each. The outcrop of green stone was exposed for several hundred feet beyond the sink and it proved to be the origin of the ruby crystals. Those rubies that had not weathered out completely were firmly held in the green zoisite matrix, as subsequent analysis in Nairobi determined the green outcrop to be.

At this particular time, with the excitement of picking up handfuls of loose ruby crystals that filled his canvas bag with thousands of carats of gleaming red gems, he remembered distinctly, three main thoughts that went through his mind. One was that he had made a discovery that would make both he and his partner extremely wealthy. Another was that he wanted to hurry back to camp to display with pride to his partner, the fabulous crystals he had loaded into his bag, so that they both could share in excited conversation the effects that this discovery would have on their futures. The third thought that kept revisiting him was the suspicion that he had finally discovered what men and expeditions had been searching for over a very long period of history, the famous long lost ruby mines of King Solomon!

Returning to camp towards the end of the day, Tom laid out all of the finer rubies in a beautiful display and then covered them with a tarp, to await the arrival of his partner. His partner arrived in camp soon thereafter, tired and discouraged, having found nothing again for all of his days’ efforts. At the proper moment, the tarp was peeled back, and with predictable results, the mood of the camp transformed into an excited clamor of comments and laughter. Early the next morning they were at the ruby locality to assess with greater care, the potential of their find.

|

| Edward Swoboda in his backyard, surrounded by large Longido ruby specimens. Photo courtesy of Edward Swoboda. |

Examining the green zoisite outcrop, the matrix that the ruby crystals were formed in, they discovered that the deep red ruby with clear portions for faceting occurred only at one end of the outcrop, at that little sink where Tom Blevins had first discovered the ruby. Here they were all flat and many were remarkably well crystallized, resembling in form some ancient hexagonal coins. They rarely exceeded two inches in diameter by a quarter of an inch in thickness. Another 150 feet along the strike of the outcrop, a noticeable change occurred to the rubies, stilt immersed in the green matrix. They became much larger but coarser in outline, changing from the thin, flat crystals with transparent areas into huge hexagonal columns of a lighter red opaque material. The most distant outcrop from the original discovery was approximately four hundred feet, at which point the exposed rubies were sparsely scattered, poorly formed and opaque, but extremely large.

Claim markers were laid out to include the total outcrop plus extensions along the strike in each direction. They also took notes on prominent features which, when sighted in by their compass, gave an angle of reading accurate enough for the registering of their claim. Having finished these details, they burdened themselves with more of the loose ruby, consisting mostly of opaque crystal sections and some very attractive specimens of flat, platy hexagonal crystals attached to small pieces of the green rock, and trudged back to camp. That evening they broke camp and returned to Nairobi.

Two weeks later they had returned to the ruby location with tools and provisions to begin mining. A not too distant village provided a convenient labor pool where they hired a number of blacks to set up a camp adjacent to the claim and to begin open cuts into the outcrop at several selected spots. During the next several weeks of mining, one or the other partner made frequent short drives to and from the local village and occasionally to Nairobi for supplies.

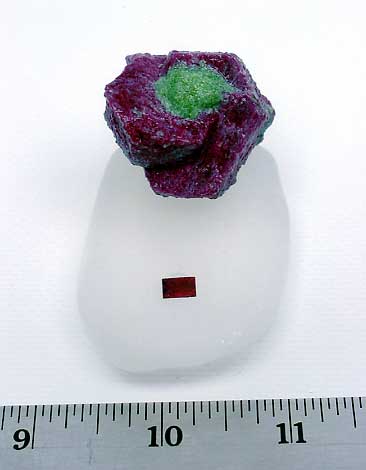

|

| A miner holding ruby in zoisite at the Longido mine. Photo courtesy of Edward Swoboda. |

An unforeseen and very strange problem developed in connection with these driving trips and persisted through the several weeks during which they used the dirt track. Elephants had toppled a six-inch thick tree which had fallen across the road. They managed to detour this roadblock at the time and did not attach significance to the event. Herd movements, following a planned seasonal itinerary of forage, leave in its wake, torn branches, trampled undergrowth and fallen saplings. Thereafter, more trees were uprooted over their access road by the elephant herd. From then on, axes and tow chains were carried to keep the road open. It became apparent to the partners, having observed these intelligent beasts for many years, that the elephants were purposely and deliberately blocking the road to discourage the unwanted visitors from passing through.

The fragments and loose flat hexagonal plaques of ruby that Tom had first come upon in the little shallow basin on the on the slopes facing Mount Kilimanjaro, contained the best and only faceting material that he and his partner uncovered. The color was an exceptionally pure dark red, with little or no yellow or brown undertones. One of several rubies Tom had cut locally weighed close to a carat, a very fine deep red flawless stone. Having no experience in beneficiating raw gem materials, Tom unfortunately listened to someone with possibly less experience than he had. Accordingly, a major portion of the better faceting rough was subjected to a thorough roasting, then quenched in cold water, on the rationale that this shock treatment would separate the cutters from the chaff. This trial, of course, added immeasurably to his reserves of chaff.

He sent a selected parcel of faceting rough to someone in Hatton Gardens in London, which was never returned to him. Little by little, the partners’ dreams of riches faded away. Several uneventful years spent in attempting to market the rubies proved fruitless and they gradually turned their thoughts and energies away from the ruby and into the mining and carving of meerschaum, a deposit of which they had also discovered.

It was during this latter period that I arrived in Nairobi. Possessing no names nor information from this part of Africa, I decided to visit a local museum maintained by the Kenyan Bureau of Mines. Espying a very attractive specimen of ruby corundum in a green matrix, I inquired of the curator-director its origin. He kindly explained that the specimen had been donated by a Mr. Blevins, a local resident, whose address he supplied me with.

|

| A small faceted Longido ruby, along with a large ruby crystal with attached green zoisite. Photo courtesy of Edward Swoboda. |

The taxi pulled up to a two story building, the address given as the headquarters of the two mining partners, just as some man was descending an outside staircase dressed in bush clothes. Hastily leaving the taxi, I hurried to intercept this man, asking if he knew the whereabouts of a Mr. Tom Blevins. He answered that yes he did and proffered his hand. At that very moment he was departing for a few days’ stay at the meershaum locality. Upon telling him of my interest in ruby corundum, he thereupon drove me directly to his home.

Arriving at his residence on the outskirts of Nairobi, he drove us around to the rear where he normally parked, an open area of ample shade trees, loose running chickens and assorted equipment and litter, including an old car with a missing wheel, supported by a huge chunk of bright green zoisite with three huge ruby crystals attached. I think my eyes momentarily left their sockets. Matrix ruby crystals were scattered everywhere. As I knelt to examine the many pieces, Tom said, motioning towards an isolated wooden framework under the trees, “The best are inside the garage.”

Unlocking and pushing wide the swinging doors to allow the light in, he invited me to enter. Two rows of rusting carbide drums met my eyes, each can filled to the brim with bright red chunks of ruby corundum. Shelves on the interior walls were clustered with dozens and dozens of plaque-like ruby crystals on matrix, some crystals up to two inches in diameter, and most of them attractively weathered to stand out from their matrices.

Two boxes of selected material resting on the carbide drums contained loose crystals and crystal sections weighing up to several thousand carats each. A huge mound of green zoisite boulders covered most of what was left of the floor space, each piece containing an exceptional attachment of ruby corundum. Just the cleaned, processed ruby—as I learned afterwards—amounted to over four and a half million carats.

Truly, I was overwhelmed, gazing speechless at this massive collection of material. My meager traveling budget gave me a feeling of hopelessness and, as I gradually began to reassemble my thinking processes, I began discrete inquiries with the hopes of at least obtaining a few of the colorful matrix specimens that were lying about. Tom explained that their disillusionment was so complete, they wanted to rid themselves of the total lot, all or nothing, in order to finance the meerschaum mining, pipe-carving, marketing business they were presently involved in.

|

| Small faceted Longido rubies, along with a large ruby crystal with attached green zoisite. Photo courtesy of Edward Swoboda. |

Gathering courage, I asked Tom what amount he was asking for everything in sight, thinking and hoping that perhaps I could find some financial backing. He answered with a double digit number that took me some time to frame an appropriate inquiry to, not knowing whether he was thinking in terms of tens of thousands of dollars or perhaps even higher amounts. When he answered that the amount he sought was only so much, a very fair price and far lower than I had expected, I sort of went into shock. I delayed responding to him for several minutes, once again attempting to gather my senses, and only then became audible with a strange remark that came out as, “and what about the freight?” Actually, I didn’t know if it were possible to ship all this material out of the country. Tom misunderstood the torpor of my delayed question and promptly offered to pay the freight also, assuring me that it would be no problem to box it up and dispatch it within a few days.

Being assured that the material would be handled by professional forwarders, I then asked Tom if the shipment could also include two tons of the green zoisite. He replies, “Yes, no problem.” At least I expected to pay extra for the zoisite, but he included that also under the original price quoted. My, what a transaction!

Returning to Los Angeles, the timing continued to prove fortunate for me in the marketing of this material. The Kazanjian Brothers gem and jewelry company had recently completed a fabulous Lincoln head carving of black star sapphire and were presently searching the world market for some big chunks of ruby, appropriate for sculpting another bust in their Presidential Series of gem carvings. The first crystal I showed them almost brought tears to those experienced eyes. It weighed several thousand carats and was a very select deep red hexagonal prism of uniform consistency that must have been just what they were looking for.

In subsequent months, the Kazanjians methodically went about obtaining all of the large ruby corundum crystals I possessed, those over three or four thousand carats each, including one mammoth crystal that weighed in excess of 30,000 carats. They eventually decided to take the total balance of the cleaned and cobbed raw ruby, weighing a total of several million carats.

|

| A small faceted Longido ruby, along with a large ruby crystal cluster with attached green zoisite. Photo courtesy of Edward Swoboda. |

Many years later in northern Tanzania, I eventually visited this now famous locale in the company of a Tanzanian government official. A guard posted at the gateway to the property questioned my travel companion severely and at length in native dialect before we were allowed entry into the frayed mining compound. The surface area was scarred with rusting equipment and dilapidated structures, in the process of slowly being overtaken by a mantle of scrub growth. These surviving remnants constituted the leftovers from years of selective scrounging from the local villagers.

Touring the property on foot, one of the several government employees straggling in our rear covertly showed me two small pieces of zoisite, each with some mangled reddish corundum splotches attached, which I politely refused. The cursory examination that I was allowed to make during this visit left me with the impression that the surface features had been swept clean of anything of note. The contention among the personnel guarding the property was that the mine was soon to be rehabilitated to continue mining the small ruby rough that it formerly supplied in such great quantities to India for the faceting of melee.

By the time they had worked over the easily accessible surface outcrops, the two partners had accumulated in all, an amazing total of over four million carats of rough ruby. The largest crystal found was in a class by itself, weighing slightly more than 30,000 carats. From the standpoint of sheer quantity, I think this locality is the largest producer of ruby ever known. In later years in the hands of new owners, shafts were driven down into the green zoisite and for many years rubies were mined, totaling hundreds of thousands of carats. Most of this production was sent to India to be cut into beautifully colored small faceted gems.

|

| A small faceted Longido ruby, along with a large ruby crystal cluster with attached green zoisite. Photo courtesy of Edward Swoboda. |