Fire-Hearted Pebbles from

Burma by C.M. Enriquez

Reprinted

from Asia magazine, October, 1930, Vol. 30, No. 10,

pp. 722–725, 733

Old as the hills are the blood-red rubies that sparkle on the fingers of beautiful women and in the turbans of Indian maharajas. Old as the hills – and, as I look out upon the tortured granite peaks of Mogok, I endeavor to appreciate the stupendousness of that antiquity. The earth was young when these molten rocks were thrust in amongst the limestone that once covered all Burma and the Indo-Chinese peninsula.

To reach the Mogok ruby mines you must travel for a day

from Mandalay up the Irrawaddy by steamer and thence for sixty miles by motor

along a road that leads through gorgeous forests toward the heart of the mountains.

The scenery is exquisite. Indeed, there is none finer in Burma, and Mogok is

on the tourist route – or should be. At last, at four thousand feet, you

come to the “Winding Valley” – for such is the meaning of the

Shan name, Mong Kut, of which Mogok is the Burmese corruption.

Picture

in the bottom of the valley two lakes – both of

them abandoned and flooded ruby mines – around

which clusters the little town of eight thousand inhabitants.

In the market place are found all sorts of strange

folk – Kachins, Lisus and Shans from the adjacent

mountains and Chinese, Shan-Tayoks and Maingthas from

across the Chinese border. Every fifth day they crowd

into Mogok to buy and to sell; for markets are still

held here as in the days of Marco Polo. It is a gay

scene, where women battle furiously for mushrooms or

orchids or rice, a whole array of mysterious and repellent-looking

jungle produce reputed, in spite of its appearance,

to be good to eat, cook or chew.

Picture

in the bottom of the valley two lakes – both of them

abandoned and flooded ruby mines – around which clusters

the little town of eight thousand inhabitants. In the market

place are found all sorts of strange folk – Kachins,

Lisus and Shans from the adjacent mountains and Chinese,

Shan-Tayoks and Maingthas from across the Chinese border.

Every fifth day they crowd into Mogok to buy and to sell;

for markets are still held here as in the days of Marco

Polo. It is a gay scene, where women battle furiously for

mushrooms or orchids or rice, a whole array of mysterious

and repellent-looking jungle produce reputed, in spite

of its appearance, to be good to eat, cook or chew.

“Old as the hills are the blood-red

rubies that sparkle on the fingers of beautiful women and

in the turbans of Indian maharajas.”

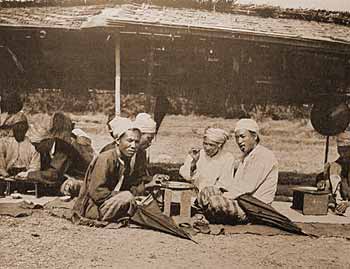

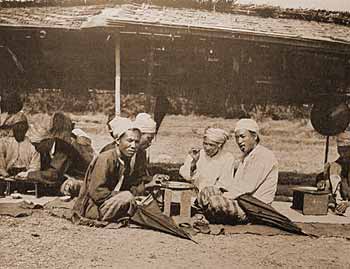

Altogether

more decorous are the crowds that collect on other

occasions to buy and sell stones. These are mostly

composed of men skilled in the art of valuing gems

or in showing them to the best advantage. There are

some jewels which may be viewed only in the sunset.

Others are bid for mysteriously, sellers and buyers

seating themselves at a table with the stones between

them and holding hands under the table. By squeezing

finger joints – which denote tens, hundreds or

thousands of rupees they arrive at a price secretly;

for a beautiful ruby, like a beautiful woman, depreciates

in value (here at least) by being publicly discussed.

Round

about rise the marvelous mountains,

placid in the sunshine, veiled with

mist in the rains, painted with azaleas

and bauhinias in the spring and with

cherry-blossoms at Christmas, when

the petals rain down upon the ground

like a gracious carpet. In winter there

is cold, scintillating sunshine, with

blue-black shadows in the forest. The

monsoons bring a rainfall of nine feet – but

there are frequent breaks. Because

of its elevation Mogok is always cool,

and the climate is pleasant and healthful.

It is as if the gods had favored the

Winding Valley with their beautiful

jewels – red ruby and blue sapphire – and

their loveliest blossoms – from

temperate peach to tropical orchid – and

as if man, for once in his life, had

decided to leave Nature alone. Tucked

away far from the outer world, isolated

amidst its sheltered mountains, Mogok

possesses that now rare quality of

being absolutely unspoiled.

|

Burma

is the home of the rubies and sapphires.

The mines of Ceylon, Siam and Indo-China

produce stones equal in color but not, as

a rule, equal in size to those of Burma.

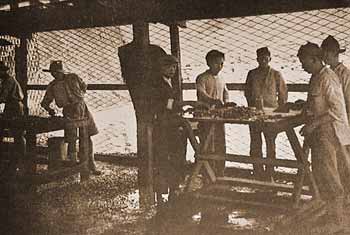

The Burmese gem mines are shallow pits worked

with little or no machinery by all sorts

of strange folk. From gravel beneath the

clay surface, clear red and blue crystals

of corundum – named rubies and sapphires – eventually

find their way to Paris or into rajas’ treasuries.

Anybody is free to wash the rubbish discarded

by the licensed miners for small stones,

suitable for watch jewels. The upper left-hand

picture shows a Chinese ruby mine, in which

the earth is raised by bamboo lifts; each

hole is one mine. |

|

|

|

Upon

it frown the surrounding peaks. The granite pinnacles

add just the correct touch of savagery to the placid

and lovely landscape. Of the limestone little is left.

The rains of uncounted ages have washed it away; subterranean

fires have changed it till no vestige remains of its

former structure. There is hardly a fossil left whereby

to date these ancient rocks. The only ones ever found

are certain Brachiopoda – terebratulae

washed out of their original site and rolled down into

the valleys along with masses of gravel, sand and rubbish,

among which occur the rubies and sapphires. Rubies

are found high up on the mountains, too, but they are

mostly worked in the new alluvial beds of the valley

bottoms where they have drifted into the chinks and

crevices of the ancient rock.

The

Burma Ruby Mines Company has worked

these deposits for the past forty years,

but now its lease is drawing to an

end. There are, besides, innumerable

native mines – some licensed and

independent, others working under the

company. But in all cases the method

of work is much the same. The surface

of reddish lateritic clay is removed

to lay bare the lower gravels, which

are the ruby-bearing strata. The appearance

of a mine is usually that of a shallow

pit, either small or large. Here and

there shafts and tunnels are dug in

special circumstances, but as a rule

the mines are open. In all these gem-bearing

localities there has been the same

violent intrusion of granite, the same

metamorphosis of what is presumed to

have been limestone. In all are found

these fire-hearted pebbles for which

women yearn and for which men fight

and toil.

“In all these gem-bearing

localities there has been the same violent intrusion of

granite, the same metamorphosis of what is presumed to

have been limestone. In all are found these fire-hearted

pebbles for which women yearn and for which men fight and

toil.”

Burma

is essentially the home of rubies. The mines of Ceylon,

Siam and French Indo-China are worthy rivals, producing

stones equal in color but not as a rule equal in size

to those of Burma. Rubies! How they tempt, charm, fascinate;

their red flame suggests earth's primeval conflagration.

Shrouded in their coat of rust, they ask the momentous

question: “Am I rendered valueless by flaws or

reduced by ‘satin’ stains to the rank of

a star ruby, which only Americans seem to appreciate,

or am I a flawless, blood-red gem worth a king's ransom?” The

sapphires ask the same exasperating question. And since

early times men have thought it worth while to risk

searching for the answer.

These

mines of Mogok in Burma were probably

discovered by the Chinese, who first

located the lead and silver of Bawdwin

and the tin deposits of Perak and Kinta.

Certain bronze spearheads of marked

uniformity found in the Mogok gravel

among prehistoric stone implements

suggest that possibly troops or police

may once have guarded the mines. In

Burmese times the mines were worked,

as now, by Burmese and cognate races – Shans,

Shan-Burmese and Maingthas – and

were the monopoly of the Burmese kings

of Ava, Amarapura and Mandalay. The

king claimed all stones over a certain

weight and quality, but, human nature

being then what it still is, many fine

rubies were cut up to defraud him of

his dues. To this day several local

village names record what the kings

thought when they discovered their

losses and what retribution they inflicted.

|

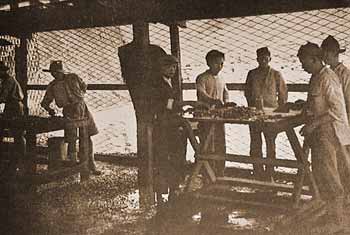

| At

Mogok, in Upper Burma, center of the ruby-mine

district, practically every one owns shares

in some sort of mine. The richest gravels

are collected for scrutiny on tables in the

sorting sheds, where guards keep close watch

over the workers to prevent them from smuggling

any gems out of the area. Spontaneous enmities

among the workers are also an insurance against

theft. |

|

The

finest ruby known to have been found at Mogok in

medieval times was the Ngamauk, which was in the

possession of Mindon Min, the last king of Burma

but one. He was excessively proud of it and showed

it to some of the foreign ambassadors who from time

to time visited his court. He valued the gem as being

worth half his kingdom. The Ngamauk Ruby descended

to Mindon’s ill-fated son, Thibaw, with whom

it remained until that day when the British army

took him prisoner in the summer-house of his palace

at Mandalay. From that day to this the famous jewel

has never been seen again. At one time or another

nearly everybody connected with the events at Mandalay

was accused of stealing the Ngamauk, and there are

a thousand ways in which it may have disappeared.

Perhaps the palace folk took it when they deserted

with cartloads of treasure. Perhaps some lucky soldier

or sepoy got it – though that is highly improbable.

Perhaps

it was given to some minister to keep

or the King himself may have retrieved

this so portable “half of the

kingdom.” Certainly he denied

possession of it and later threatened

to prosecute the British government.

“The Ngamauk Ruby descended

to Mindon’s ill-fated son, Thibaw, with whom it

remained until that day when the British army took him

prisoner in the summer-house of his palace at Mandalay.

From that day to this the famous jewel has never been

seen again.”

The

finest stone dug up in recent times is the forty-three-carat “Peace

Ruby” – reduced as cut to twenty-four carats – discovered

on Armistice Day and later for sale in Paris for

thirty thousand pounds, I believe. Stones so huge

are difficult to dispose of in these days when crowns

and regalia are a drug on the market. Paris consumes

most of the Burma rubies. It would surprise most

persons to see the apparently poor Burmese with agents

of their own in the rue de la Paix and the wretched

cottages here in Mogok in which priceless jewels

are kept in a cigarette tin.

|

| Men

skilled in valuing gems assemble at Mogok.

Certain jewels are bid for mysteriously,

sellers and buyers seating themselves with

the stones between them and holding hands

under the table. By a code-squeezing of fingers,

they arrive at a price secretly; for it is

thought that a beautiful ruby, like a beautiful

woman, depreciates in value by being publicly

discussed. |

|

Life

in Mogok is a lottery in which the poorest has a chance,

and, if he happens to have nimble fingers and toes and

a disarming smile, he has a good chance. Any one may find

or steal a fortune any day. A small mine, which can be

worked for about one hundred and fifty rupees a month,

is usually financed by a little group. At the end of the

month some drop out and others take their places. Practically

every one in Mogok owns shares of this kind and lives on

in hope – mostly in hope – of a windfall to come.

You have to trust your partners, and this trust is a far

greater strain than might be imagined. The only practical

way of running a business on these lines is to give the

actual workmen a handsome share in the profits and then

to pick those who are deadly enemies, so that each will

watch the others like a cat. The recruiting of deadly enemies

should not be difficult in any Shan community, but the

worst of it is that they fall out of hate as easily as

they fall out of love.

Even

when loot combines them in an unholy friendship,

however, they usually fall out over the

spoils – but for which happy fact

no one in Burma would ever get any rubies

at all.

|

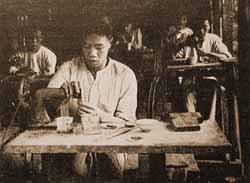

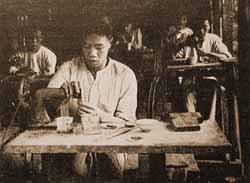

| Some

stone-cutters of the Burma gem mines

carry on their delicate work with equipment

consisting of an old sewing machine or

part of a dismantled bicycle. |

|

|

Palagems.com

Ruby Buying Guide

By Richard

W. Hughes

Introduction. The

term ruby is reserved for corundums of a red

color, with other colors called sapphire. In

Asia, pink corundums are also considered rubies.

Outside of Asia, such gems are generally termed

pink sapphires.

Color. For

ruby, the intensity of the red color is the primary

factor in determining value. The ideal stone

displays an intense, rich crimson without being

too light or too dark. Stones which are too dark

and garnety in appearance, or too light in color,

are less highly valued. The finest rubies display

a color similar to that of a red traffic light.

Lighting. Rubies

generally look best viewed with incandescent

light or daylight (particularly around midday).

Avoid fluorescent tubes, which have virtually

no output in the red end of the spectrum, and

so cause ruby to appear grayish.

Clarity. In

terms of clarity, ruby tends to be less clean

than sapphire. Buyers should look for stones

which are eye-clean, i.e., with no inclusions

visible to the unaided eye. In the case of some

rubies, extremely fine silk throughout the stone

can actually enhance the value. Many rubies also

display a strong red fluorescence to daylight,

and this adds measurably to the beauty of this gem.

While

a certain amount of

silk is necessary to

create the star effect

in star ruby, too much

silk desaturates the

color, making it appear

grayish. This is not

desirable. While

a certain amount of

silk is necessary to

create the star effect

in star ruby, too much

silk desaturates the

color, making it appear

grayish. This is not

desirable.

Cut. In

the market, rubies are found in a variety of

shapes and cutting styles. Ovals are cushions

are the most common, but rounds are also seen,

as are other shapes, such as the heart or emerald

cut. Slight premiums are paid for round stones,

while slight discounts apply for pears and marquises.

Stones that are overly deep or shallow should

generally be avoided.

Cabochon-cut

rubies are also common.

This cut is used for

star stones, or those

not clean enough to

facet. The best cabochons

are reasonably transparent,

with nice smooth domes

and good symmetry. Avoid

stones with too much

excess weight below

the girdle, unless they

are priced accordingly. Cabochon-cut

rubies are also common.

This cut is used for

star stones, or those

not clean enough to

facet. The best cabochons

are reasonably transparent,

with nice smooth domes

and good symmetry. Avoid

stones with too much

excess weight below

the girdle, unless they

are priced accordingly.

Prices.

With the exception of imperial jadeite and

certain rare colors of diamond, ruby is

the world‘s most expensive gem. But

like all gem materials, low-quality (i.e.,

non-gem quality) pieces may be available

for a few dollars per carat. Such stones

are generally not clean enough to facet.

The highest price per carat ever paid for

a ruby was set on February 15, 2006, when Laurence Graff, a London jeweler, paid a record $425,000 per carat ($3.6 million) for an 8.62-ct. ruby, set in a Bulgari ring, at a Christie’s auction in St. Moritz.

Less than a year before, on April 12, 2005, an

8.01-ct. faceted stone sold for $274,656

per carat ($2.2 million) at Christie’s

New York. Previously the record for per-carat

price was held by Alan Caplan’s Ruby

(‘Mogok Ruby’), a 15.97-ct. faceted

stone that sold (also to Graff) at Sotheby’s New York,

Oct., 1988 for $3,630,000 ($227,301/ct). Less than a year before, on April 12, 2005, an

8.01-ct. faceted stone sold for $274,656

per carat ($2.2 million) at Christie’s

New York. Previously the record for per-carat

price was held by Alan Caplan’s Ruby

(‘Mogok Ruby’), a 15.97-ct. faceted

stone that sold (also to Graff) at Sotheby’s New York,

Oct., 1988 for $3,630,000 ($227,301/ct).

Stone Sizes. Large

rubies of quality are far more rare than large

sapphires of equal quality. Indeed, any untreated

ruby of quality above two carats is a rare stone;

untreated rubies of fine quality above five carats

are world-class pieces.

Phenomena. Ruby

may display asterism, the star effect. Fine star

rubies display sharp six-rayed stars well-centered

in the middle of the cabochon. All legs of the

star should be intact and smooth. Just having

a good star does not make a stone valuable. The

best pieces have sharp stars against an intense

crimson body color. Lesser stones may have sharp

stars, but the body color is too light or grayish.

On occasion, 12-rayed star sapphires are found.

Inexpensive star rubies come mainly from India.

|

|

This

4.86-ct. star ruby from Pala International

is one of the finest examples to come out

of Mogok in years.

(Photo: John McLean;

Gem: Pala

International) |

Name. The

name “ruby” is believed to be derived

from the Latin ruber, a word for red. According

to Oriental beliefs, ruby is the gem of the sun.

It is also the birthstone of July.

Sources. The

original locality for ruby was most likely

Sri Lanka (Ceylon), but the classic source

is the Mogok Stone Tract in upper Burma. Fine

stones have also been found in Vietnam, along

the Thai/Cambodian border, in Kenya, Tanzania,

Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yunnan (China) and most

recently, Madagascar. Low-quality rubies also

come from India and North Carolina (USA).

Enhancements. Today,

the vast majority of rubies are heat-treated

to improve their appearance. The resulting

stones are completely stable in color. Many

rubies are also heated in the presence of a

flux to heal their fractures, particularly

those from Möng Hsu, Burma. In lower qualities

and smaller sizes, heat treated stones sell

for roughly the same as untreated stones of

the same quality. However, for finer qualities,

untreated stones fetch a premium that is sometimes

50% or more when compared with treated stones

of similar quality. Other treatments, such

as oiling, dying and surface diffusion are

seen on occasion. As with all precious stones,

it is a good practice to have major purchases

tested by a reputable gem lab, such as the GIA or AGTA,

to determine if a gem is enhanced.

Imitations. Synthetic

rubies have been produced by the Verneuil process

since the 1890’s and cost just pennies

per carat. Ruby has also been produced by the

flux, hydrothermal, floating zone and Czochralski

processes. Doublets consisting of natural sapphire

crowns and synthetic ruby pavilions are fairly

common, particularly in mining areas. Synthetics

are also common at the mines, in both rough

and cut forms.

|

Fine

ruby specimens. The crystals are from, from

left to right, Afghanistan, Vietnam and Tanzania,

while the two faceted gems are from Mogok,

Burma.

(Photo: Harold & Erica Van Pelt; Gems: Pala

International). |

Properties of Ruby

| |

Ruby (a variety

of corundum) |

| Composition |

Al2O3 |

| Hardness (Mohs) |

9 |

| Specific Gravity |

4.00 |

| Refractive Index |

1.762–1.770

(0.008) Uniaxial negative |

| Crystal System |

Hexagonal (trigonal) |

| Colors |

Various shades of red.

Ruby is colored by the same Cr+3 ion that

gives alexandrite and emerald their rich hues. |

| Pleochroism |

Strongly dichroic:

purplish red/orangy red |

| Phenomena |

6 or 12-rayed

star |

| Handling |

No special care

needed |

| Enhancements |

Frequently heated;

frequently flux-healed; occasionally oiling,

dying, surface diffusion |

| Synthetic

available? |

Yes |

For further information on

ruby, see also:

For further information on

Burma, see also:

|

|

While

a certain amount of

silk is necessary to

create the star effect

in star ruby, too much

silk desaturates the

color, making it appear

grayish. This is not

desirable.

While

a certain amount of

silk is necessary to

create the star effect

in star ruby, too much

silk desaturates the

color, making it appear

grayish. This is not

desirable.