Imperial Topaz by Peter Bancroft

Vermelháo, Antonio Periera Mines, Dom Bosco, Brazil

Editor’s Note: We are pleased to reprint this selection from Peter Bancroft’s classic book, Gem and Crystal Treasures (1984) Western Enterprises/Mineralogical Record, Fallbrook, CA, 488 pp.

|

T

hree mall areas—Dom Bosco, Rodrigo Silva, and Saramenha—comprise most of the topaz belt west of Ouro Prêto in Minas Gerais. All three areas were known to gem prospectors working the region as far back as 1730. Brazil was a colony of Portugal then, and the impoverished mother country was delighted with the significant topaz discovery at Villa Rica (Ouro Prêto) in 1735. In 1768 the Portuguese government officially recognized the find as a commercial gem deposit—which only followed Brazil’s other major riches of gold and diamonds in importance.

Ouro Prêto rapidly became the most prominent town in the state of Minas Gerais and, during the late 1800s, its capital. Stone buildings with tiles roofs were constructed during the Portuguese administration, including the Liberty Pantheon and the Governor’s Palace. The latter, now a museum, contains a fine 25,000-specimen collection of Brazilian gemstones, crystals, and minerals. The museum is an important feature of the national School of Mines. Brazilian mineral dealer Luizelio Barreto tells of a staircase within an Ouro Prêto monastery, which is paved with topaz crystals and cleavage sections.

|

| Classic Imperial Topaz. Size: 5 by 2.5 cm. Locality: Saramenha, Brazil. Collection: William Larson. Photo: Harold & Erica Van Pelt |

Ouro Prêto mines produce orange to pinkish-purple topaz. Often the stone has been confused with the more common citrine (which is made by heating amethyst) found profusely in other Brazilian localities. However, topaz is readily identified by its superior hardness, density, and brilliance, as well as by a pronounced basal cleavage. In the early days topaz was the only gem of importance found near Ouro Prêto. Honoring Brazilian royalty, the gemstone was frequently referred to as “imperial” topaz. Later some sources called it “precious” topaz. Both terms have endured, partly because gem merchants wish to impart to customers the difference between gem topaz and citrine quartz.

|

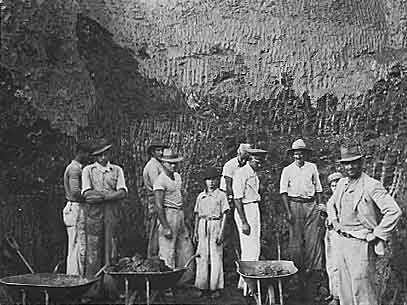

Topaz mine at Dom Bosco, 1938. Photo: Edward Swoboda |

Common topaz crystals are prisms which generally measure from 5 to 3 centimeters. The largest reportedly measures 50 by 8 centimeters and probably a score of crystals have been found in lengths over 15 centimeters. The larger specimens often were broken along cleavages, however, and little care was taken to keep the pieces of each crystal together for repair; thus few such giants exist intact today.

|

| Mining topaz near Ouro Prêto, 1938. Photo: Edward Swoboda |

In addition, nearly all larger crystals are heavily flawed and contain little if any cutting material. An exceptionally large and rich golden brown topaz is in the collection of the Los Angeles County (California) Natural History Museum. It is 28 centimeters long.

|

| Wood-burning train leaving Governador Valadares for Belo Horizonte and Ouro Prêto, 1953. Photo: Peter Bancroft |

Ouro Prêto has consistently been the world’s major source of golden topaz. Tons of crystals have been mined in the low hills west of town, but only a very few out of each 1000 crystals produce a facet-grade gem weighing more than one gram. Rare crystals with transparent sections of a remarkable sherry or muscatel color sometimes occur and a few produce flawless 100-carat stones of incredible beauty. When peach-hued prisms are placed in ovens and heated, a fraction of them change to pink. This color transition is permanent—but at the risk of fracturing the gems.

|

| Old topaz workings at Saramenha, ca. 1976. Photo: Wendell Wilson |

The 4- to 6-kilometer-wide topaz mining zone extends from Mariana in the east to Sao Juliao in the west, a distance of about 44 kilometers. Most golden topaz occurs within this zone. Outstanding individual mines have been the Lavra do Moraes, Vermelhao, Lavra do Trino, Lavra do Capão, and the Antonio Pereira.

|

| Ouro Prêto, 1977. Photo: Helmut Leithner |

Gem crystals occur in kaolinite clays (some stained by iron), penetrated by quartz veins. Topaz crystals also are commonly found in sedimentary iron formations composed chiefly of hematite and silica, known in Brazil as itabirite. Much of the original country rock has been eroded and reformed into a light conglomerate. If pegmatites ever existed in the Ouro Prêto region, little remains of them now. There is an absence of tantalum minerals, and pegmatitic minerals such as feldspar, mica, and heavy “native” tin.

Topaz matrices form in two types: crystals imbedded in limonite and crystals attached to white quartz. The latter are quite rare, and topaz terminations are frequently damaged during the mining process. Doubly terminated topaz crystals occur uncommonly in the region but are frequently found at the Vermelhao mine.

|

| Euclase. Size: 4.5 by 2 cm. Locality: Dom Bosco. Collection: Hermann Bank. Photo: Karl Hartmann |

In 1973, topaz in rich sherry colors of superior quality was uncovered at Saramenha at the Vermelhao (Antonio Pereira) mine, but no appreciable amount of euclase has been mined. Clear quartz crystals with topaz inclusions are reported from the Lavra do Trino mine near Rodrigo Silva. Beautiful quartz with liquid inclusions has been found in a number of Ouro Prêto mines.

Topaz has been esteemed since the Middle Ages, when wine-yellow crystals were mined in the Erzgebirge mountains at Schneckenstein (near Auerbach, East Germany). Hundreds of kilograms of yellow to brown topaz crystals were mined there and Schneckenstein was the main source until the discovery of the Ouro Prêto deposits. It was popular among Europeans as a talisman which prevented bad dreams, calmed passions, ensured faithfulness and, when taken in wine, cured asthma and insomnia. Tradition has it that Lady Hildegarde, wife of Theodoric Count of Holland, presented a topaz to a monastery in her native town. At night it emitted a light so bright that prayers could be read without the aid of candles in the chapel where it was kept. The statement might well be true if the monks knew the prayers by heart.

|

Girl washing for euclase and topaz, 1978. Photo: Peter Keller |

A prime world source of the lovely euclase is at Boa Vista near Rodrigo Silva, where sharply-terminated brilliant crystals occur in delicate shades of blue, green, yellow, and lavender. Euclase forms in prismatic crystals hard enough to serve for jewelry, but cutters must be alert for nearly perfect cleavage planes along with crystals readily part. The stone is quite rare, and gemmy colored sections rarer still. Author L. von Eschwege described a long-lost euclase crystal unearthed during the 19th century at Boa Vista, which weighed 750 grams. Few crystals exceed 4 centimeters in length. Associated minerals have little economic importance or significance as crystal specimens. The following occur: ilmenite, smoky and milky quartz, schorl, the rock itacolumite (a micaceous flexible sandstone), and topaz. Two species form in exceptional crystals: hematite “roses” growing in topaz-laden veins have measured up to 20 centimeters in diameter. Small but beautiful rutile crystals also sometimes appear.

|

| Working in sump for topaz at the Capão mine at Rodrigo Silva, 1978. Photo: Peter Keller |

As late as 1965, a wood-burning locomotive pulled freight and passenger cars over the 80-kilometer route between Belo Horizonte and Ouro Prêto. Packed with people, crates of chickens and ducks, and piles of cargo, the train stopped at every little hamlet along the way. The trip, which took a little over four hours by train, can be accomplished by automobile in about an hour today.

Considerable activity continues along the Ouro Prêto topaz belt. A bulldozer scrapes away the overburden at the Vermelhao mine near Saramenha, sometimes breaking into old meandering tunnels which for scores of years have harbored lost lunch pails, lamps, and tools. The Capão mine Rodrigo Silva also bustles with activity. Miners work with picks and shovels at Dom Bosco—just as other miners did before them more than 200 years ago. The gem shops of Ouro Prêto, Belo Horizonte, Rio de Janeiro, and Sao Paulo sell beautiful topaz crystals. Recently mined crystals of topaz are equal in quality and may match in size the best found years ago. A few 10- to 12-centimeter gemmy crystals of a deep golden brown were offered for sale in 1980 in the United States and Europe. Best of all, gem topaz production is at an all-time high, and optimism pervades the entire topaz mining district.

|

About the author. Dr. Peter Bancroft was Marketing Director of Pala International in the mid-1970s. He is also the author of The World’s Finest Minerals and Crystals and has written for many publications in Europe, Australia and the United States. Dr. Bancroft is a well-known lecturer on mines, minerals and gemstones.

In contrast to many “armchair authors” who merely recycle what has appeared in other books, Dr. Bancroft has spent years traveling the world like a modern-day Herodotus, visiting hundreds of remote and fascinating mineral and gem deposits, and interviewing miners and local inhabitants. Bancroft has uncovered a wide range of information, some of it never before published. This and his extensive knowledge of the literature have combined to produce an authoritative and highly readable text.

Although many fine specimens reside in public collections such as the Smithsonian Institution and the British Museum, Bancroft has searched further through a vast number of private collections worldwide in order to assemble the suite of magnificent photographs found in Gem and Crystal Treasures. Many specimens in these collections are rarely if ever available for public view.

Dr. Bancroft has done graduate work in geology at the University of Southern California, The University of California at Santa Barbara, and at Stanford University. His doctorate, in Education Administration, is from Colorado State University. During his long professional career he has served as teacher, principal, and superintendent of schools in California; as a White House consultant on education, as a professional photographer; as a gemstone buyer, as Curator of Mineralogy at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History; and as Director of Collections for the San Diego Gem and Mineral Society.

His personal mineral and crystal collection has won state and national honors. In 1984 he was selected as an Honorary Awardee for the American Federation of Mineral Societies’ Scholarship Foundation.

Dr. Bancroft’s son, Edward, has a collection that can be seen in the Dept. of Geological Sciences at the University of California at Santa Barbara. A beautiful introduction is online at: The Bancroft Collection.

Today, Peter Bancroft resides with his wife Virginia in Fallbrook, CA. Those wishing to correspond with him can contact him at:

Dr. Peter Bancroft

3538 Oak Cliff Drive

Fallbrook, CA 92028

USA

Palagems.com Imperial Topaz Buying Guide

Introduction/Name. Topaz is the name for the mineral species that is number 8 on Mohs’ scale of hardness. There is some uncertainty regarding the name. Some say it comes from the Sanskrit word meaning “fire.” Others link it to the Red Sea Island of Topazios (Zabargad or St. John’s Island), where peridot has been found.

For the general public, topaz means a yellow gem, and much citrine and smoky quartz has been sold as “golden topaz” and “smoky topaz.” The terms “imperial” and “precious” topaz are often used to distinguish between true topaz and the quartz look-alikes.

The name “imperial topaz” is said to have originated in the 19th century in Russia, where the Ural Mountain mines were an important source. According to some sources, pink topaz from those mines was restricted to the family of the Czar. Today, the gem trade generally uses the term for pink, orange and red topaz, which comes mainly from Ouro Prêto, Brazil. Fine pink topaz also comes from the Katlang area of Pakistan.

|

| Three different flavors of imperial topaz from Brazil. 4.8 cm. high. The most highly sought would be the pink gem at right. Gems: Pala International. Photo: Robert Weldon |

Color. Topaz commonly occurs in colorless and brown colors, it is the rare golden, orange, pink, red and purple colors, which are often termed “precious” or “imperial” topaz, that are the mainstay of the fine gem market. While blue topaz is found in nature, most of the material is produced by a combination irradiation/heating treatment.

Yellow and brown topaz owe their color to color centers. The impurity chromium produces pink to red colors. A combination of color centers and chromium produces orange topaz. Blue topaz is colored by color centers.

Note that the color of some brown topaz may fade with time.

Lighting. Due to its orange to red-orange color, topaz generally looks best under incandescent light. In contrast, blue topaz looks best under daylight or fluorescent light. When buying any gem, it is always a good idea to examine it under a variety of light sources, to eliminate future surprises.

|

| A gorgeous brown topaz crystal from the Mogok region of Burma. 4.8 cm. high. Carl Larson collection. Photo: Jeff Scovil |

Clarity. Topaz from most sources is reasonably clean. Thus eye-clean stones are both desirable and possible. The exception is with pink and red topaz, where only small stones are normally available. In those colors, a slightly higher degree of inclusions are tolerated.

Cut. Due to the shape of the rough (elongated prisms), topaz is generally cut as elongated stones, typically emerald cuts, elongated ovals, cushions and pears. To save weight, pears in particular are often cut with overly narrow shoulders. Due to the huge production, blue topaz is cut in virtually any shape and style one can imagine. Cabochon-cut topazes are rarely seen.

While topaz does have a perfect basal cleavage, it is not an easy cleavage, and so does not present too much difficulty to the cutter. Nevertheless, cutters will often try to ensure that no facet is parallel to the cleavage direction and jewelers try to mount valuable stones in settings that protect the stone.

|

| Magnificent intergrown brown topaz crystals from the Mogok region of Burma. 8.5 cm. high. William Larson collection. Photo: Jeff Scovil |

Prices. The prices of topaz are, like any gem, dependent on quality. Still, a few generalizations can be made. Blue topaz, the most common variety seen in jewelry today, has been produced in such quantities that today it is generally available for $25/ct. at retail for ring sizes. Larger sizes may be slightly more. While natural blue topazes are known, the huge production of treated blue topaz has essentially dropped the price of the natural blue down to that of the treated stone.

Colorless topaz, from which blue topaz is produced (via irradiation and heat), is available in sizes up to 100 cts. and greater, and sells for less than $8/ct. Brown topaz fetches similar prices.

In contrast, precious topaz (a.k.a. ‘imperial’ topaz) in rich orange colors fetches prices in excess of $1000/ct. for large (10 ct. +) sizes. The most valuable topaz is a rich pink or red color, and can reach $3500/ct. at retail. These are rare in sizes above 5 cts.

Stone Sizes. Topaz sometimes occurs in enormous sizes, where clean gems of even 1000 cts. are known. Indeed, faceted stones of tens of thousands of carats have been produced from some monster crystals. However, cut stones of the prized “imperial” colors (orange, pink and red) are more rare. Fine pinks and reds above 5 cts. are scarce. Fine oranges above 20 cts. are also rare.

|

| Three different examples of treated blue topaz. Gems: Pala International. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul |

Sources. Gem topaz has been found at a number of localities around the world, including Brazil, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, Russia, Burma, Pakistan, USA and Mexico. The premier source is near Ouro Prêto in Brazil’s Minas Gerais state.

Enhancements. As previously mentioned, several varieties of topaz are typically enhanced. Most common is the combination irradiation/heat treatment that produces blue topaz. For this treatment, colorless topaz is irradiated, turning it brown. The stone is then heat treated, which turns it blue. While the brown color is generally unstable, fading with prolonged exposure to sunlight, the blue color is generally stable under normal wearing conditions.

There are three main flavors. The first, a “sky” blue, is produced by gamma rays (cobalt 60). Deeper “Swiss (a.k.a. ‘windex’) ” and “London” blues are produced by high-energy electrons (cyclotron) or nuclear radiation. In the latter case, the stones must be allowed to cool down to safe levels of radioactivity before being sold. This typically takes a few months to as much as two years.

Another treatment seen on occasion with topaz is bulk diffusion, where stones are heated for long periods surrounded by cobalt. This drives the cobalt into a thin layer at the surface, turning it green to blue. The layer is extremely thin.

Finally, some topaz is coated with metallic oxides, similar to the coatings on camera lenses. This produces various colors and rainbow-like reflections, but the coatings are easily scratched. The material has been marketed under the name “rainbow” topaz.

Imitations. Topaz has never been synthesized, but a number of imitations exist, including natural stones such as citrine and smoky quartz, and man-made imitations such as glass.

|

| A magnificent 15.45-ct. imperial topaz from Brazil previously offered by Pala International. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul |

Properties of Topaz

| Composition | Topaz has the following composition: Al2(F,OH)2SiO4 |

| Hardness (Mohs) | 8 |

| Cleavage | Perfect (but not that easy) basal cleavage |

| Specific Gravity | 3.53 ± 0.04 |

| Refractive Index | 1.619–1.627 (±0.010) |

| Crystal System | Orthorhombic; usually occurs as vertically striated elongated prisms topped by domes |

| Colors | Orange, yellow, brown, blue, pink, colorless, rarely red |

| Pleochroism | Weak to moderate, dichroic |

| Dispersion | 0.014 |

| Phenomena | None |

| Handling | Ultrasonic: not safe; never clean topaz ultrasonically Steamer: not safe The best way to care for topaz is to clean it with warm, soapy water. Avoid exposure to heat, acids and rapid temperature changes. Strong heat may alter or destroy color. |

| Enhancements | Various Most blue topaz is made by irradiation and then heat; this treatment is undetectable and extremely common. Blue topaz irradiated with in nuclear reactors can emit dangerous levels of radiation; it must be allowed to cool down to safe levels before sale. Some orangy topaz is heated to destroy the color centers, leaving behind the chromium-caused pink color. |

| Synthetic available? | No |