Burma, The Mineral Utopia

By Martin L. Ehrmann, Certified Gemologist

The following three-part article was published in the August (this part), October and December editions of The Lapidary Journal in 1957.

Introduction by The Lapidary Journal

We are indeed happy to present in a three-part series an account of Burma and its gem mines by one of America’s leading gem authorities, internationally known for his work in the coloring of diamonds by cyclotronic bombardment. The author recently returned from an extensive gem buying trip in Burma and his gem travels have taken him all over the world many times. As this article appears he will be returning to Burma. Ehrmann was co-author, with Herbert P. Whitlock, in the writing of the book The Story of Jade.

Part One

|

When I was much younger and joined the New York Mineralogical Club during the late twenties, I used to dream about a place where minerals were begging to be picked up—a mineral Utopia! I kept right on dreaming. At many outings to the Bedford, New York, quarry, and to Strickland, Connecticut, pegmatite and Paterson, New Jersey, zeolite localities, few minerals were collected by any of us. When someone did make a find, he was immediately surrounded by all to admire with awe the piece of rose quartz, single tourmaline crystal or small prehnite that could have been bought from a mineral dealer for ten cents in those days. Nevertheless, they were wonderful outings which I thoroughly enjoyed. It was great to be with the other rockhounds to talk about minerals and gems we had picked up at other localities, stressing the size and particular beauty of our own specimens; not unlike the tall tales of fishermen after a trip. It was fun to be away from the city and enjoy the sunshine, pure air and picnic lunches. Mineral collecting was then in its infancy in the United States. With the tremendous increase in the number of rockhounds in the succeeding years, I wonder how many are dreaming of a mineral Utopia now.

After many years, I can report that I have found my mineral kingdom. For the sum of about five thousand dollars to cover traveling and living expenses for a couple of months, you, too, can share this Utopia by taking a trip to Burma. Until that time arrives, I am happy to share this adventure which occurred in the regular line of my business. I guarantee that a rockhound outing to Burma would be most successful—each member would come home with at least one piece of nice spinel, ruby, topaz, peridot, quartz in all varieties, small pieces of more than two hundred and fifty mineral specimens, and some rare gems. Do share this most interesting and satisfying trip with me by way of the following pages.

Geography

Entry into the mineral kingdom world is Rangoon, the capital city of Burma. Rangoon has a population of about 800,000 people consisting of approximately 550,000 Burmese, 125,000 Chinese and 125,000 Indians. All Burma has a population of 18,000,000. Burma, or the Union of Burma as it is now called, is divided into six states. They are Burma, Shan, Kachin, Kayah, Chin and Karen. It is a long, narrow country, bordered by India and Assam on the West, by Tibet and China on the North and by Siam on the East. By contrast with India and other Asiatic countries, the people of Burma seem prosperous, well-fed and well-clothed.

Rangoon is a rather impressive city with wide, well-laid-out, pleasant streets and many beautiful parks within the city limits. However, ravages of the Second World War are still seen in the many bombed-out buildings with all their rubble. The slum sections, too, are as anywhere in India, with crowds and filth clearly visible.

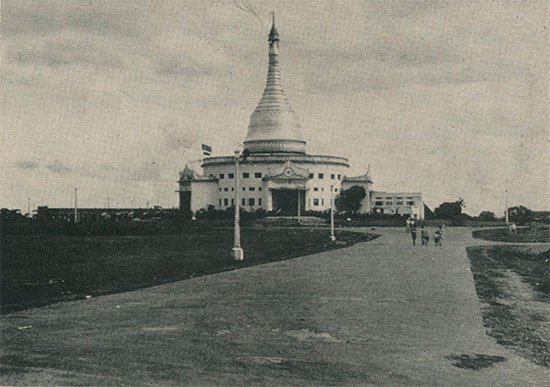

The residential section of the city is well-kept. Many beautiful mansions stand majestically on Prome Road, the finest residential street in the city. There are many temples and pagodas of beautiful architecture, though less elaborate than those in Siam. The Sula Pagoda is in the center of the city with a tower over fifty feet high covered with 24Kt gold leaf to which gold is added regularly every few years. This gold is reputed to be worth many millions of dollars. The Shwedagon Pagoda is located in the residential area on a lovely landscaped two-mile square. This Pagoda with its golden spire glittering in the sunlight is the largest and finest Buddhist temple in the world and worth millions of dollars.

|

| One of the many pagodas in Rangoon, Burma. The spire is covered with solid gold leaf worth many millions of dollars. |

The University of Rangoon is another interesting landmark. It is well-known as the finest higher education institution in the Far East and is staffed by a fine international faculty. It consists of many buildings on a huge campus, with a mixture of old and modem architecture.

Burma’s transportation system is poor. The railroad going North from Rangoon is old, dilapidated and extremely slow. A trip to Mandalay, a distance of 450 miles, takes about three days and is very dangerous. Each train leaving Rangoon is preceded by an armored car with a complement of soldiers, as these trains are frequently attacked by marauding bands of insurgents roaming the jungles of Burma. Even this protection does not prevent frequent attacks and much loss of life. Another mode of transportation is by slow, crowded and uncomfortable river boats on the Irrawaddy River, the most important river in Burma, navigable for about 1000 miles. Such a trip is a combination of three days of train travel to Mandalay, two days by boat to Thabeikian and sixty miles by automobile to Mogok.

It is air travel that offers the finest mode of transportation within Burma. The Union of Burma Airlines flies to all points North, using Dakotas and DC-3s, flown by Burmese pilots trained in England. These two-motor planes are found best for the short distances flown. There are two daily flights to Mandalay and flights once a week to the capitals of all other states, thus making air travel the only efficient way to get to Mogok. A plane leaving Rangoon once a week at 8:00 a.m. arrives in Momeik about noon and is met by a jeep for the twenty-eight mile drive to Mogok. This brief jeep trip is usually accompanied by an element of danger as the roads are frequently mined by the insurgents, political enemies of the state, who roam the jungles and frequently blow up or hold up cars. There is also the ever-present danger of the highway bandits who steal everything of value but seldom kill.

Nevertheless, the drive to Mogok is fascinating. As Momeik is 800 feet above sea level and Mogok is 4000 feet above, there is a continual climb through extraordinary country, scenically the most astounding in all Asia. Occasionally, green valleys appear through thick jungles; then, suddenly, terrible desolation and ruined pagodas come into view. Here and there is a village beyond which are picturesque rice paddies. The roads are deteriorated and appear to have had no care in years.

|

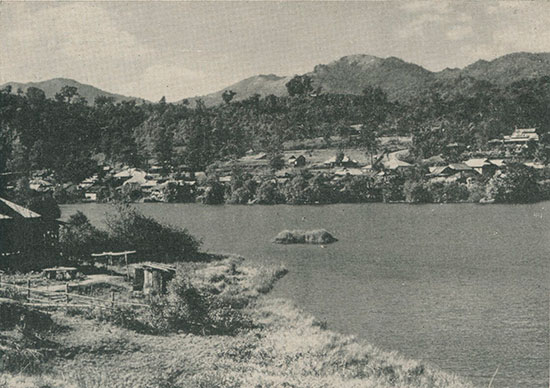

| Lake in Mogok formed by twenty-five years’ digging for rubies and sapphires in the gem gravels by the Ruby Syndicate. |

Mogok is situated in a magnificent valley, surrounded by majestic mountains studded with temples and pagodas—some very modem, others thousands of years old. Geographically, Mogok is considered a part of the Burma State although it is actually located in the western part of the Shan State. This fact dates back a long time, before the English occupation of Burma when it was a kingdom and all of Burma was ruled by Burmese kings. Because of the vast wealth in the Mogok area, the kings retained their hold on it and fought the Sab Bwas (same as maharajas of India) who tried to wrest it from them.

Even under British rule, the Mogok area was kept as a separate entity, an independent state. A British commissioner was appointed for this area alone. Until Burma became a republic, uniting all six states, only the State of Burma was actually the Kingdom of Burma. The other five states were ruled by Sab Bwas who are still powerful politically, all holding ministerial rank. As Sab Bwa of his own state, he is the minister representing his state in the Union government and usually holds another political office as well.

The Mogok valley is about twenty miles long and two miles wide. In the center of the village of Mogok is located a beautiful lake created by digging for precious stones during the Ruby Syndicate era. The Mogok gem area reaches to the city of Momeik, a distance of thirty miles to the North and sixty miles to the West, up to the villages of Twingwe and Thabeikian on the Irrawaddy River.

Mogok has a moderate climate. During winter, the maximum temperature is 25° during the night and early morning. During the day, it goes up to 70°. In summer, the evenings are mild and the maximum day temperatures are about 95°. It is a heavy rainfall area, ranging from 90 inches of rain to 135 inches in the rainy or monsoon season from May to November.

The chief industries of Burma are the cultivation of rice and the logging of timber, mainly teakwood. Both commodities are exported to many countries, accounting for Burma’s only source of foreign exchange. Mogok is the exception. The only industry in the entire area of Mogok is the mining of gemstones. There is hardly any cultivation in this area; consequently even rice, the staple food, has to be brought in from Momeik.

In addition to the temples and pagodas one sees in the mountains, there are various plants of gorgeous colors; bright blooming magnolia trees and cherry blossoms are abundant. One shrub, similar to rhododendron, grows all over the mountains. The natives are superstitious about these rhododendron shrubs, believing that they are created by the good spirits hovering in the area and called “the gods of the mountain.”

Wild life is also abundant. Many varieties of birds can be seen almost any time of day. Elephants, tigers and diverse species of the deer family thrive in the mountains and nearby jungles.

People

Nowhere in the Orient does one find more smiling and friendly people than in Burma. They dress neatly and use exquisite colors in their materials. Both men and women wear skirts or longhis, and both sexes delight in bright colors and silk attire. A longhi is a skirt-like garment. Cotton longhis are used for daily wear; silk longhis are worn on holidays and for special occasions. The longhis are very wide to give plenty of room to the wearer and are stepped into, folded and knotted in front. It is not unusual to see a man or woman open the longhi while walking, shake it with graceful motions and retie the knot, all in the twinkling of an eye, with unconscious, mechanical precision. The men generally wear sport shirts with their longhis; the women wear sheer, white blouses adorned with ruby and sapphire gold buttons. In startling contrast to the rigid customs in India, the life of the Burmese is free from the effects of any caste system and seclusion of women—which may account for their pride in gay dress. In the interior, even though less civilized, the people of the various tribes have their distinctive and picturesque modes of dress and adornment.

In the section of Burma which borders on Assam, Tibet, Yunan Province of China and French Indo-China live the peaceful Shans, the warring Kachins and the headhunting Nagas. These people have their own unique dress which is also very colorful. The women wear hats of a large turban-type made of gay materials. In their noses, they wear a gold drop which is fastened to the center of the nostril and hangs down below the mouth—a most awkward place for a pendant. But in every part of Burma, all the Burmese have one thing in common—a fierce pride in their newly-gained independence and freedom from English rule since 1948.

U Khin Maung, my agent and interpreter, had made arrangements for us to stay at his parents’ home, a typical Mogok hut built on a concrete slab with woven bamboo walls and native wood beams. Upon our arrival, we were given a fine welcome by his parents, two younger brothers and a sister. I was given a cot in the corner of the living room. In all the homes in Mogok, the living-rooms serve a dual purpose as they are also the family’s private shrine. In one corner, a pagoda occupies the most prominent place in the room. In front of it is a table on which are placed flowers and bowls of rice, changed daily as offerings to Buddha. Daily prayers, in a prone position, are said morning and night to Buddha. According to the Buddhist religion, no one can enter a pagoda with shoes on, so everyone takes off his shoes before entering the living room of any house in Burma.

All homes in Mogok have another common feature—the complete absence of any sanitary facilities. Outhouses are found in the rear of the huts. Water for washing and cooking is brought in from pumps, sometimes found in the rear but more frequently in front of the huts. Baths are taken at these pumps in full view of the entire population. Both men and women manage their longhis so gracefully that the dry one is on before the wet one is completely off. My first attempt at bathing in the street almost turned into a fiasco because I wasn’t quick enough in changing from the wet to the dry longhi. Although no one was visible at the moment, I heard much laughter from my invisible audience. After practicing a few times, I also became adept in the quick change.

Our first evening in Mogok, we retired early after a typical Burmese dinner, a tasteless, thin soup containing mustard-like greens, followed by white rice in curry sauce with bits of pork and vegetables, and tea. About 6:00 a.m., I was awakened by the morning prayers of all our neighbors. We ate a good breakfast—two boiled eggs, bread and butter and coffee, using the canned butter and Nestle’s instant coffee I had brought along. We started our tour of the town with a courtesy call to the S.D.O. (subdivisional officer) who acts as Mayor, Chief of Police, Fire Chief and Magistrate, as well as Chief Mining Inspector. His name was U Hla Tint, a charming young man of about thirty, with a pleasing personality. He is respected by all the 20,000 inhabitants of the area. He gave us a most cordial welcome and promised to give us advice and help in any way we wished. After the customary cups of coffee and tea, we departed, assured that we would have all the cooperation we needed from the law in Mogok.

We visited a number of the most important mine owners and dealers from whom I gathered much essential information. The procedure in visiting these people was invariably the same—the minute we arrived, shed our shoes and sat down in a squatting position, cups of coffee were served. This coffee was unlike any coffee I have ever tasted. Apparently the coffee, milk, sugar and water are cooked together, and the sugar was plentiful. It had a sickeningly sweet taste, but we finished it and were immediately offered cups of tea which tasted good after the first overly sweet concoction. The number of cups of coffee and tea we imbibed each day depended on the number of visits we made. A sincere feeling of welcome everywhere we went made me feel at home.

Mining and Geology

The Mogok area is the only place in the world with a population of twenty thousand people earning a living from gemstones. Except for diamonds and pearls, almost every variety of gemstones, both precious and semi-precious, has been found there. The total gem area is approximately 1916 miles. Gem deposits are found within an eight mile radius of Mogok, and there are about 1200 individually owned mines operating in the area. Every house in Mogok is a lapidary shop.

There are two types of operation in mining. After an area has been discovered showing signs of gemstones, the top layer of sand is removed, sometimes to a depth of fifteen feet. When the gem gravels become visible, the real work begins. Depending on the size of the area, from three to twenty-five miners begin to loosen the gem gravels, the large boulders being discarded on the sides. The smaller gravels are gradually shoved to a pile in a convenient corner by shovels and picks. In most mines around Mogok where water is plentiful a centrifugal pumping system is used to pump the gravels up to a high point with an eight inch pipe. A wooden structure capable of holding up to forty tons receives all the gravels. At a specified time of day, the gravels are washed in the following manner. The miners who loosened the gravels come into the structure and remove the largest pebbles by hand. The balance is pushed through a wire mesh to the first level, then to the second and finally to the third or bottom. Thus, the large pieces are held on the first level, smaller pieces on the second and the smallest on the bottom. At this point, the washing operations actually begin. This is a top secret operation; only the mine owner and his own miners are present during this final step. No one is supposed to learn what luck the mine had on any particular day.

|

| Typical alluvial gem mine in Burma. One of about 1200 in the Mogok area. |

The gravels on the lowest level are now taken out in wire baskets and thoroughly washed again. Many pebbles are removed by hand and the balance is carried by each miner to a picking table 4 x 8' in size. The mine owner and his assistant stand there moving the gravels with a metal blade in one hand. The other hand is used to pick out all gems which are then placed in a bamboo container while the other gravels are pushed off the table. Such gravels still contain small pieces of rubies, sapphires and other gems with which the mine owner does not think it worthwhile to bother. This material is gathered into piles which are sold to the poor women relatives of the mine owner. After purchasing one or two piles for a very small sum, the women comb them for all remaining gems. If, by some chance, the mine owner has overlooked a large gem, it rightfully belongs to the woman purchaser of the pile in which it is found. All this is a rapid operation, with the results quickly seen.

The other method is to dig square wells to depths of twenty-five to thirty feet. To prevent the walls from caving in, the miners shore them with bamboo rods. After a hole is secure, the mining process begins. The gem gravels are brought to the surface in rattan baskets raised by a rope-like drawing water from a well. The gravels are then washed and the precious stones removed.

Rubies and associated minerals such as spinels are formed in a matrix of white, dolomitic, granular limestone. These rocks have been altered by contact with molten, igneous material which recrystallized the calcium carbonate as pure calcite, while the impurities became the rubies, spinels and other minerals. Rubies are seldom found in this matrix now. All mining is in the adjacent alluvial ground.

The origin of the Mogok gem area has not been described anywhere, as there has been no scientific investigation made to date. My own superficial observations indicate that there are at least two hundred and fifty mineral species within the area. It is safe to say that the Mogok area gems are of metamorphic origin. The original rock in which these gems were formed disintegrated on the earth’s surface. Loose disintegrated soil was formed in which the gem minerals, such as rubies, sapphires and spinels (which are not harmed by water and other atmospheric conditions), were imbedded and remained in excellent condition. This integration was washed away by waters and the gems were washed along as well. Eventually, the waters stopped flowing and the gravels remained, being covered by sand layers of from five to fifteen feet where they are waiting to be discovered. New areas are opened daily where new finds are continually being made. Rubies are known to occur in three important tracts in Upper Burma, but the original source of the gems is found to be highly crystalline limestone.

The variety of minerals found in these mines varies a great deal. Statistics are difficult to obtain because of the previously mentioned secrecy prevailing. I did, however, obtain the cooperation of one mine owner in this respect, a jovial Burman, U Nyunt Maung, one-man owner of the largest mine in the Mogok area. According to him, about 70,000 carats of rubies and sapphires are mined there yearly. Of unusual interest is the fact that only 1% of spinels come from this mine. These rubies and sapphires are not all of gem quality. A good guess would be that less than 5% of the 70,000 is of decent quality; only ½ of 1% is of gem quality. Other varieties of gemstones found here are danburite, scapolite, beryl, zircon, amethyst and fibrolite. In addition, many varieties of iron minerals and rare earths occur here, such as monazite, ilmenite, columbite and tantalite.

In Kathe and Kyatpyin, the first six miles and the latter eight miles from Mogok, in addition to individually-owned mines employing five to fifty miners, there are also large tracts of land leased to individual miners who work a few feet of the area by the hole-digging method previously described. As this area is rather dry, most of the gem gravels are piled up in huge piles and are washed during the months of the rainy season. Although not considered a rich area, it still provides about a half million dollars worth of rubies and sapphires annually.