|

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Richard

Hughes is an author, gemologist, and ex-webmaster

of Pala International, Fallbrook, California. He

also has his own personal web site: www.ruby-sapphire.com

Nicolai

Kuznetsov is president

of Stoneflower, a Moscow-based

company specializing

in Russian gems, minerals,

and fossils. © 2000 Richard

W. Hughes

This article originally appeared in GemKey Magazine , Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 58–66.

Abstract: Up until recently, gem-quality imperial jadeite was found only in Upper Burma. But starting in the early 1970s, jadeite was found at Itmurundy in Kazakhstan. A few years later, fine jadeite was found in the Polar Urals at Pusyerka, and in 1992, in Khakassia, about 100 km. outside of the capital of Abakan.

This article is the first extensive description ever published in English on the Russian jadeite deposits and is based upon visits by Nickolai Kuznetsov to these deposits in the early 1990’s and both authors’ visit to the Polar Urals and Khakassia mines in August, 2000.

|

IT IS AN OLD AXIOM that precious stones are rarely found in good places and nowhere is that more true than with jade. Burma, the world’s premier source features mines located in a miserable piece of SE Asian shrubbery that would have even George of the Jungle screaming for Agent Orange. Thus when I learned that top-grade jadeite had been discovered in Russia, I quickly made plans to expect the worst. Topped up my life insurance, said my last goodbyes to relatives and friends, gave away my collection of Velvet Underground records and canceled my lifetime subscription to the Watchtower. That last one really hurt.

My companion and guide for my Russian sojourn was Nickolai Kuznetsov, a Kazakhstan-born Russian whose love of gems and minerals is matched only by his prodigious consumption of vodka.

Our journey to the Russian jade mines began in the capital of Moscow, a citywide case of schizophrenia caught somewhere between Tzarist excess, a Joseph Stalin commie habit and a burgeoning case of youthful freedom. Moscow is a beguiling collection of contradictions.

The first stop in Moscow was Stoneflower, Nickolai’s mineral and gem company, housed in Andreievsky Monastery, which dates to the 16th century. It was here that I viewed my first Russian jade, and also here that I drank my first Russian vodka. Both events would be repeated many times during my three weeks in the country.

|

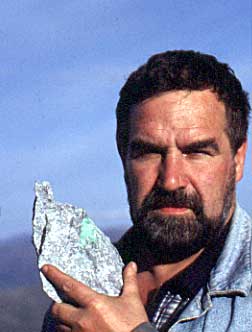

| Nickolai

Kuznetsov of

Stoneflower Co.,

holding a large

box of rutile

specimens from

the Caucasus

Mountains in

his Moscow office. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

Two days later, we set off for Salekhard, from Sheremetevo #2, one of Moscow’s six airports. At some point in the Soviet period, it was decided that an airport was needed for each point on the compass — a sweet thought, but one that makes for pure hell when flying into Moscow with the idea of changing planes and departing in a different direction.

Polar!

At Salekhard,

we are met by Sergei Mikheev,

one of the discoverers

of the Polar Urals jade

deposits. From Salekhard,

a short ferry ride across

the River Ob brings us

to Labutnangyi, but not

without incident. Our captain

ripped a rail off another

ferry leaving the dock.

No doubt he had been hitting

the vodka. A one-hour drive

brings us to Kharp, at

the base of the Ural mountains,

where we will spend the

night. One thing about

the roads up here is that

you don’t need to

worry about driving at

night, because during the

summer, there isn’t

any — night, that

is. August in the Arctic

Circle is the time of “white

nights.” When the

sun does dip below the

horizon, it is for just

a brief period, before

coming back just two or

three hours later.

|

| Local produce — Russian vodka and ornamental jadeite from Kazakhstan. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

|

| Map

showing the important

jadeite localities

in Russia and

Kazakhstan. (Illustration © 2001 Richard W. Hughes) |

Kharp is quite frankly, depressing, a monochrome mixture of rust and concrete, a gray gulag of a town, whose major industries are cement and prisons. Even the sky displays a leaden, industrial quality. Not even the slightest attempt is made at gaiety or beautification, as if even the thought is too much work under these harsh conditions.

This is the land of permafrost. While no snow is visible, only the first few feet of earth are thawed; below that all is frozen. To beat the cold, All the houses are built above the ground and insulated pipes also run above ground. At times, one sees telephone poles sticking out at crazy angles, evidence of the yearly cycle of freezing and thawing that makes it impossible to anchor anything into the soil.

|

| The Polar Ural town of Kharp, jump-off point for the Polar jadeite deposits. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

We arrive at the Kharp “Sheraton,” our night stop, a dimly lit above-ground cellar. Take a cheap Indian brothel, reduce the size of the windows and paint everything gray and you’ll get the picture. But our room does have an attached kitchen. This is a common feature in Russian hotels, for the concept of restaurants and dining out is a new one in the former Soviet Union. Even today, years after the fall of communism, less than one percent of the population of Russia takes more than one restaurant meal per year. Yes, per year.

|

| The armored personnel carrier that transported the author to the Polar Urals jade mines. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

Tanked

up

Transport to the mines,

some 160 km from Kharp, was via a Russian armored

personnel carrier (APC). After climbing aboard in

a vacant lot in the middle of Kharp,

our driver turned over the engine and the roar called out: “Are you ready

to RUMMBBBBLLE?” Verily. Banking quickly out of the lot, one city block

later we encountered a river. Whoosh, our vehicle splits the water like

Moses parting the Red Sea. Then it was up onto the opposite bank and thus began

one helluva ride. I felt simultaneously like a can of paint in a shaker and Rommel

in a blitzkrieg on the Russian steppes. Tree in the way. No problem — drive

right over the sucker. Rivers? We crossed several that were close to two meters

deep. Over hill, dale, mound, rock, and every other manner of obstruction. Mud,

rocks, trees — nothing could stop us. After my 1996–97 visits to Burma’s

jade mines, I thought I knew what a bad road looked like, but these polar paths

were their equal to the nth degree. The difference was our vehicle, which

made mincemeat out of every type of terrain thrown at it.

After an hour of white knuckling across tundra, river and forest, I turned to Nicky and asked about just how far away these mines were. With a sly smile he replied: “Only nine more hours.” “Nice,” I thought as I chewed on my tongue. If I ever do get down off this tundra tank, my butt cleavage will make Dolly Parton look flat-chested.

|

Timeless

Scenery along the way

was just beyond spectacular. Treeline this far

north is probably less

than 500 meters above sea level, with

the highest peaks in the

Polar Urals topping just over 1000 meters. But it is hard to be a tourist

amidst the roar and bounce of this Russian Taiga

tank. Occasionally we would pass

a small settlement, but otherwise there

was little sign of human activity. Only

wave upon endless wave of forest, green hills and tundra. After three hours

of

bone-jarring action, we crossed a small rise and came to a river. Standing

along the bank was a wizened old man

with what looked like all his worldly possessions

on a small wheeled luggage cart. Obviously waiting for the next bus to Nowheresibirsk.

He flags us over and blurts out something in Russian. Translation: “What

day is it?”

|

| White-knuckling it across the Polar tundra. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

|

| Geologist Sergei Mikheev, with a piece of Polar jadeite. After ten years of looking Sergei discovered the first piece of jadeite in the Polar Urals. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

Mine

at last

Nine

hours into our journey and I’ve made an important

decision. Upon my return to Moscow, I will register

a complaint with the Russian highway department,

and then go right into the pearl business, because I cannot take these jade

roads

anymore.

The KGB had no need for torture. All that was necessary was to bring a prisoner up here. Ten hours of this road and anyone would give up state secrets. How did I come to be here? How did John Hinkley come to shoot Ronald Reagan. I don’t know. I have no fixation with Jodie Foster, I have no answers, but am obviously just as nuts as Hinkley.Eventually we arrived at the mine site, Pusyerka, also known as Lot 88. A few ramshackle mine buildings showed evidence of past mining activity. How anyone ever discovered a gem up here is beyond belief. The country just oozes emptiness. It would be beautiful, were it not for the thought that, in a day or two, we will have to make this same journey back down the road.

Exploration for jade in the Polar Urals was begun by a Russian geologist named Yevgeny Kuznetsov (not related to Nickolai). In 1979, geologists mapping the area discovered rocks favorable for the formation of jadeite. Sergei Mikheev joined the yearly expeditions in 1985. Patiently they explored, during the three months per year when the snow and ice yielded to the sun. In the summer of 1989, Sergei reached down and picked up a stone that would change his life. Incredibly enough, after ten years of looking, he had found his first piece of jadeite. And it was no ordinary jadeite, but imperial jade, of a quality that compared favorably with the fine material from Burma.

|

| Green

veins are

clearly visible

in this large

block of

jadeite at

Lot 88 in

the Polar

Urals jade

mines. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

Sergei took that first piece to Hong Kong, where he showed it to one local jade trader. Only a trace of imperial green was visible at the surface. When Sergei voiced his belief that the green vein would continue throughout, he met only skepticism. So Sergei made the Chinese an offer. The stone would be sawn open. If the green continued throughout, Sergei would receive his asking price. And if the green disappeared, the Chinese would pay his much lower offer. As the saw blade parted the boulder, the tension was palpable. When it reached the end, each half of the boulder tumbled away, revealing a fine emerald-green color within. Sergei’s belief in his stone was vindicated. And the Chinaman became a believer. He later invested heavily in the mining, but alas, could not wring enough profit out of it to continue.

|

| Nickolai

Kuznetsov

demonstrating

how large

jadeite blocks

are split

for transportation

at the Polar

Urals jade

mines. Photo: © Richard

W. Hughes |

88 different outcrops of jadeite have been identified in the Polar Urals. At Lot 88, we could see remnants of the mining activity. Everywhere along the ground lay pieces of white jadeite, riddled here and there with veins of intense green. The jadeite in this area occurs in dikes within a serpentine matrix, with actinolite and phlogopite and from all appearances much material remains. But there is that old bugaboo, the weather. Today, the mine lies fallow, awaiting another visionary investor, someone who can see the promise in the green stone. And Sergei continues in his belief that if the right investor can be found, the icy green stone from the Polar Urals will take its place alongside Burma in the pantheon of imperial jade.

|

Fortune strikes

Shortly after returning

from the Polar Urals, Nickolai and I found ourselves

shooting a game of pool in a Moscow taproom when fortune smiled upon us. We were

approached by Mikhail “Misha” Khronlenko, a manic man sporting a perpetual

cat-that-ate-the-canary grin. An old friend of Nickolai’s, Misha also happened

to be Russia’s biggest jade miner and exporter. After much banter and vodka

during dinner the next evening, Misha told us he would be leaving soon for his

jade mines in Khakassia and invited us along. As Misha explained it, “every

dog gets his day.” If we would come with him to Khakassia, he promised “a

fantastic day.”

Not so fast. With the experience of the ten-hour Polar ass-cracker fresh in my mind, I needed to know more. Just where were these mines? Misha smiled and replied that they were just two hours outside the capital on a good road. Oh, real-lah? How could we refuse? A day later we found ourselves on a plane bound for Abakan, capital of Khakassia.

Let me say this from the outset. Air Abakan is not the Concorde. Not even the Konkordski. No sleep at all. I spent most of the flight obsessing that if the seat in front of me moved back even one more centimeter, the air hostess would have to remove me with a decal scraper. Over six hours after deplaning, the Air Abakan bird logo from the seatback in front of me was still plainly visible on my crushed nose. Which wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, considering that my blocked nasal passages hindered entry of the airline’s unique aroma.

The Republic of Khakassia lies in Siberia, just north of Altay and Tuva, near the border with Mongolia. Indeed, a walk through the market in Abakan shows a strong Mongolian influence, with perhaps 10–20% of the population being of Mongolian origin. But ethnic mixtures abound. I’ll never forget seeing one family walking down the street. Both mother and father displayed prominent Mongolian features, with round faces, black hair and narrow eyes that would have been entirely in place in Beijing. Their child had identical features, except for one — blond hair — testament to the fact that Khakassia has been a crossroads of conquerors for centuries.

The capital, Abakan, means “bear’s blood,” a reference to a local legend of its founding. It was founded in 1693. Today the population is 160,000. According to legend, in the early days a large bear took a liking to the local ladies, particularly those who were young and beautiful. This bear ate so many young virgins that the Hun declared that any man who could slay the bear could marry his daughter. In the ensuing fight, one man stabbed the bear over and over. The bear’s blood flowed out, clearing the valley and forming the river. Thus the name, Abakan, which means “bear’s blood.” If this isn’t enough, Ghengis Khan is said to have buried his treasure somewhere in Khakassia. It was never found.

The jade mines in Khakassia are situated near the banks of the Yenisey River, near Sayano-Shushenskaya, one of Russia’s largest hydroelectric dams. A two-hour drive from Abakan brought us to the lake created by the dam. From here, the mine lay some one-and-a-half hours across the lake by boat. Forest is everywhere. After Moscow, the air up here almost chokes you with its clarity. Thirty-six hours without sleep and I am exhausted. But eventually I move beyond exhaustion, where an epiphany is reached and I realize just why I travel. Here I am, out on a lake in the middle of Siberia, and all is well, all is peace, all is right in the world. Russia is such a land of contrasts — amazing!

|

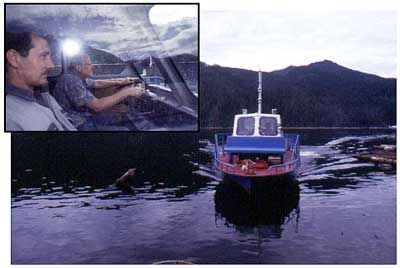

| The author getting down to serious business — piloting a boat on the Yenisey River, near the Khakassia jade mines. Due to the large number of logs floating in the reservoir, one must remain ever vigilant. The year before my visit, Misha was on a boat in this reservoir and, not paying attention, hit a swimming bear. Needless to say the bear was not happy. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

Truckin’

Arriving at the mining camp,

we were greeted by Misha’s brother and father

and were pleasantly surprised at the comfortable Siberian accommodations, complete

with banya. The mine employs some twenty people and the climate allows mining

over seven months per year. To get to the mines, we hopped in a truck and took

off on one of those incredibly steep, muddy tracks that seem to be found only

on the way to a jade mine. We could have walked, but I guess when you are drinking

a liter of vodka a day, walking is not really an option.

|

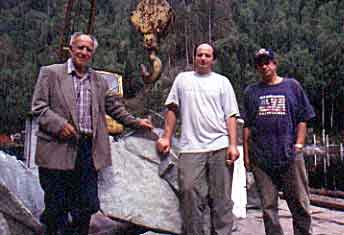

| Mikhail “Misha” Khronlenko

(center) and his father Yakov Borisovich

(left) and brother Sergei (right), owners

of the Khakassia jade mines. They are standing

in front of a huge chunk of Khakassia jadeite. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

There is something about a jade mine that seems to bring out the worst in roads. An intense five-minute drive later, we arrived at the mine. Amidst a hillside open cut stood what is probably the single biggest jadeite boulder I have ever laid eyes on. Workers crawled across its surface like ants, sticking their jackhammer stingers in to pry away small bits, which were loaded onto waiting trucks. As I marveled at the scene, Misha was beaming. “What do you think?” he asked. “It’s incredible,” I gushed. “Yes,” Misha answered, laughing that manic laugh: “Every dog gets his day.”

|

| Working a house-sized boulder of jadeite at the Khakassia jadeite mines, near the Yenisey River. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

Kidnapped

The next day it was back down to Abakan, where we proceeded to consume copious

quantities of vodka as Misha regaled us with stories of jade and life in

Siberia. Early the next morning, we rushed to the airport, only to find

that the Air Abakan flight was full.

After missing our plane, I expected a couple restful days in Abakan, but Misha had other plans. The previous night’s vodka fest had left each of us with little sleep and far fewer brain cells, but that did nothing to stop our dynamo guide, Misha. We paid a visit to a gold miner in a nearby town, and then it was off to a dacha in the countryside. Two-and-a-half hours drive later, I was beginning to understand how Patty Hearst must have felt. Eventually, we arrived at a lake. I was in miserable condition, with too little sleep and too many miles on my body, thinking to myself, “Why am I here?” I really am too old for this jade mines stuff.

The next day, recovering, I climbed a mountain above the lake. While dark clouds swirling above my head and a hawk traced lazy circles off the cliff at my feet, the answer appeared. Looking out upon the hills, the sheer vastness of the land finally beats open the doors to my consciousness. These hills and steppes stretched on unbroken for thousands of miles in every direction, the largest wilderness left on the planet. It had a calming effect. Even as the rains forced me down off the mountaintop, the sun was shining in my mind and heart.

In Dreams

Down

below, we had a

final meal before

departing for Abakan

and I had an opportunity

to speak with Misha

about his dream.

He was born in

Khakassia and has

a deep love of

his homeland and

its peoples. His

family was once

rich and powerful,

but when a brother

married an American

student in Moscow

and immigrated

to the USA, they

were ostracized

from Soviet society.

Misha went through

a number of different

businesses, everything

from truck driver

to vodka maker

before being told

one day of the

jade that had been

found in his homeland.

He was immediately

smitten, deciding

then and there

to make it his

life’s work.

|

| Product of Russia. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

Misha’s decision seemed ever more right when his wife read to him an encyclopedia entry on jade, which stated that, next to colored diamonds, jade was the most precious of all stones. And so he set out to learn all he could about the subject, visiting Hong Kong, studying up on this gem that he hoped would become his life’s work. “I have looked at all the jade deposits in Russia and Kazakhstan,” Misha told me. “The Polar deposits have fine material, but the conditions are too severe, while the quality of material from Kazakhstan is not good enough. But here in Khakassia, we have the perfect combination — an accessible deposit with good material. I know it is not as good as the best from Burma, but it is quite nice and I am positive that with hard work, we can be successful.”

As we packed our bags to leave, one building next to the lake caught my eye. It sported a window, but where the glass should be, the frame was filled with bricks. Above, clouds clashed in the sky. This seemed to symbolize all that is Russia today. Looking outward, but after 80 years of communism, somehow afraid of what she might find. Mother Russia moving, like the clouds, simultaneously in two opposite directions.

We hit the road as the sun’s final glow began to fade. A more beautiful sunset I have never seen. Stopping the car, Misha and I look each other in the eye, smiling, then take in the vast Siberian expanse that lies before us. He tells me: “Khakassia — this is a big, big country. We are small.” Just then, a rainbow shoots down through the clouds. As we embrace I tell him, “Now I understand why you brought me here.” I think to myself that I've discovered that lost treasure of Ghengis Khan. “Yes,” he nods knowingly. “Every dog gets his day. Every dog gets his fantastic day.”

|

| Russia. The country just oozes emptiness. Photo: © Richard W. Hughes |

![]()

|

Acknowledgments:

A journey such as this cannot be completed without

the help of many people. First and foremost, William

Larson, of Pala International, who gave me the time away

from work to follow my dream. And my Russian buddy, Nickolai

Kuznetsov, who allowed me to stumble in and out of trouble,

but was always there with a steady hand when needed. Our host

in the Polar Urals, Sergei Mikheev took the time to show us his

dream. Dzhano Akhvlediani from Georgia was a fine traveling companion,

always reminding us when our vodka glasses were empty. Sasha

Agafonov and the rest of the gang at Stoneflower in Moscow. And

finally, Misha Khronlenko and his brother, Sergei, and father,

Yakov Borisovich, who so willingly opened up their Khakassian

home and homeland to us.

For more on jade, see: Burmese Jade: The Inscrutable Gem